By Logan Meyer, A&E editor

In his directing debut, Jordan Peele, known for his sketch comedy work in the Comedy Central show “Key & Peele,” presents “Get Out,” a masterful if somewhat unorthodox amalgamation of comedy and thriller.

The film opens with an eye-level shot of a suburban sidewalk, poorly lit by streetlamps. Though it’s hardly a frame from “A Nightmare on Elm Street,” the cinematography wastes no time establishing the film as a satirical, ironic reimagining of the quintessential suspense thriller.

Though it is certainly far from the only film to mock horror with comedy (“Scary Movie” anyone?), “Get Out” sets itself apart with a glaring and overwhelming focus on racial tension in the United States.

“Get Out” tells the story of Chris (Daniel Kaluuya) and his girlfriend Rose (Allison Williams) as they venture to her parents’ house together for the first time. Chris is predictably reticent to see how Rose’s parents, Missy and Dean, will react to their interracial relationship, but finds his concerns to be unfounded, at least at first.

In an effort to ease any fears of racism, Dean says he would’ve voted for former president Barack Obama a third time if he could’ve. Peele clearly wrote the film as a timely commentary on black-white relations, with the common excuse, “I’m not racist, my best friend is black,” in mind. More than other films have done before, “Get Out” proves that such a statement is not, in fact, substantive enough.

After meeting the family’s servants, who are also black, Chris’ reticence returns. Both servants behave as if lobotomized. Slowly, it becomes more apparent that perhaps his original fears weren’t entirely unfounded. Upon discovering numerous articles of incriminating evidence, Chris deciphers that Rose and her family are in the habit of, for lack of a better word, hunting black people.

Dean ever-so-kindly alleviates the audience’s curiosity as to why. He states simply that he and his family recognize that while white people have a mental edge, black people are physically superior. For this reason, they believe it beneficial to find the happy medium between the two.

Of course, Peele couldn’t write in a montage of generations peacefully cooperating and breeding selectively to better their offspring. No, that would be too peaceful. Besides, no comedic horror film would be complete without surgical scenes unfit for children and the weak-stomached.

That’s right, Dean’s a neurosurgeon. And what self-respecting neurosurgeon doesn’t have an operating room in their basement? A ridiculous, highly fantastic chain of events ensues as Dean attempts to fuse the consciousness of a dying white man with Chris’ peak physical condition.

After a compelling action scene, the movie ends in a violent bloodbath. Unsurprisingly, audiences are far from torn in their feelings on said murderous rampage.

“Get Out” makes it abundantly clear that white people are crazy, and audiences will undoubtedly protest the film for taking its point too far. While that may be true, that is indeed the point of satire. It is certainly no more an overstep than the powerful majority has performed in the past.

“Get Out” is, for many reasons, a gem.

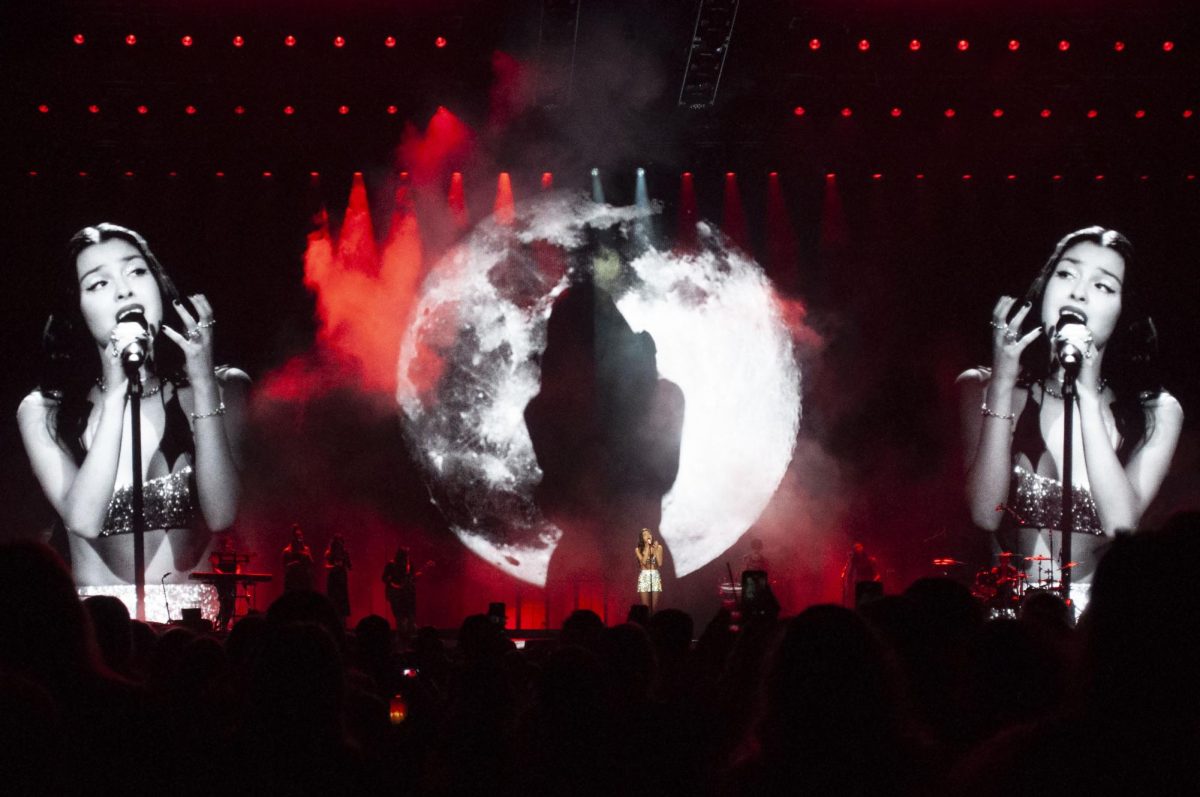

Photo courtesy Getty Images