Justice Breyer brings his pragmatism to Boston

April 3, 2018

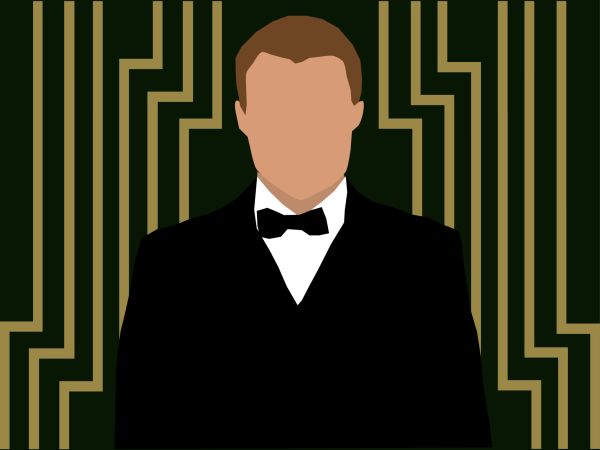

Since his appointment in 1994, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer has made a name for himself as a pragmatist. This means that in contrast to some of his fellow justices, Breyer is known to take the context of his court’s rulings into account when making a decision, avoiding an end-all-be-all interpretation of the Constitution. But during a public forum on hate speech and the First Amendment Thursday at Boston’s Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate, he upheld the First Amendment as untouchable.

“The first thing to remember about the First Amendment is that it’s there for people whose speech you don’t like,” Breyer said. “Speech can do harm. But, the greater harm is to put somebody up as a censor to decide when it goes too far.”

Jeffrey Rosen, a legal commentator and president of the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, served as moderator. He said Breyer’s approach to the First Amendment is distinctive.

“It’s unlike any of your colleagues,” Rosen said to Breyer. “You have argued that the value of speech should be balanced against its social cause, and that rather than being categorical, it should be reasonable.”

Breyer pushed back against this notion, explaining that it doesn’t matter what he specifically thinks, but rather what the courts decide. However, his versatility as a justice surfaced in his response as well.

“I think life is a mess,” Breyer said. “If you go and write something too definite for the indefinite future, it’ll come back and hit you in the face.”

Following Breyer was a panel of experts moderated by Rosen, who discussed differing perspectives on the First Amendment. Jud Campbell, an assistant professor of law at the University of Richmond, said Breyer’s pragmatism didn’t go far enough.

“At the end of the day, the justice still honors this notion of sanctity toward the First Amendment,” Campbell said after the panel discussion. “I don’t think governmental regulation should be feared as much as it is. Speech really has a lot more power than people may think.”

Campbell’s fellow panelists Stephen D. Solomon, a professor of journalism at New York University, and Nadine Strossen, former president of the American Civil Liberties Union, disagreed.

“This is not a binary question,” Strossen said. “Hate speech should only be suppressed if and only if it creates a clear and present danger.”

During a reception before the event, Shahrier Emon, a software engineer from Dorchester, said he was eager to hear what the justice would say on the power of the First Amendment.

“The notion of hate speech is cringe-worthy,” Emon said. “It screams censorship to me. Justice Breyer is known to toe the line in his decisions, and to hear him address the First Amendment in a public forum will be enlightening.”

Dennis Naughton, a former high school principal from Foxborough, was also in attendance. He is the chair of his town’s Democratic Party; he was also interested in hearing Breyer’s opinion on such a volatile issue.

“I’m curious to see what he has to say, considering he is a minority in the court and a minority within his minority,” Naughton said.

Breyer’s 2010 dissent to the court’s controversial Citizens United decision argued that corporations should not be considered members of society and that the power of their speech can have a negative impact on the outcome of elections.

“In cases like these, the game is worth the candle,” Breyer said. “Otherwise you’d find so many people silenced by massive entities.”

At the end of the event, when Rosen asked the audience to vote on whether or not the First Amendment should protect all speech, including hate speech, Breyer smiled when the outcome was a unanimous ‘yes’.

Rosen then asked Breyer if he feels optimistic about the survival of democracy.

Breyer smiled as he said, “I’m very biased, but I don’t think my grandchildren are so bad.”