Work hard, work harder: the uproar of internalized capitalism in the digital world

Photo courtesy of John de Graaf

Students at Western Washington University at Take Back Your Time Day celebrations.

December 29, 2021

It’s the start of a new year. For many, January is the month of starting — and never finishing — a New Year’s resolution list. For accountants, the notorious month offers much more than a fresh start with no promised finish line. It’s the beginning of a new tax season and the clock to make it to the end of April is ticking.

Alexander Arenas, a third-year business administration major, knew how intense his job would be. Before going into his first co-op in January 2021 as a real estate tax intern at Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdeler, or KPMG, one of the four largest accounting firms in the world, Arenas read up about the workload on forums. He learned that it was unheard of for accountants to have no work in the “busy season,” which lasts from January to April.

Arenas worked hard. So hard, in fact, he was experiencing the near-impossible — he was running out of work to do. On these days, Arenas would ask his senior associates over video calls for more work to do, to which they told him to enjoy the time he had off. You don’t need to work all the time, they told Arenas.

“It felt unnatural to just sit and wait for more work to come in,” Arenas said. “I felt like if I was not billing hours to clients, then I wasn’t being productive enough.

The feeling of needing to constantly produce and get work done, even when there is none, is a widespread feeling shared beyond hardworking accountants. The term coined by experts to describe this phenomenon is “internalized capitalism,” and it has taken a toll on many, especially college students in their transition from school to the work field.

“Internalized capitalism is when the worth of an individual is tied to their level of productivity or how much they can produce [and] create,” said Marvin Toliver, a therapist at Radical Therapy Center in Philadelphia. “Internally, we have this idea that we have to always be working, and if we’re not, then we’re lazy. We feel bad for not doing work.”

Capitalism is a centuries-old system, and tying someone’s self-worth to how productive they are is not a new phenomenon. However, as the work field shifts into the digital world, it creates a new factor that amplifies an individual’s internalized capitalism — comparison of productivity through digital platforms.

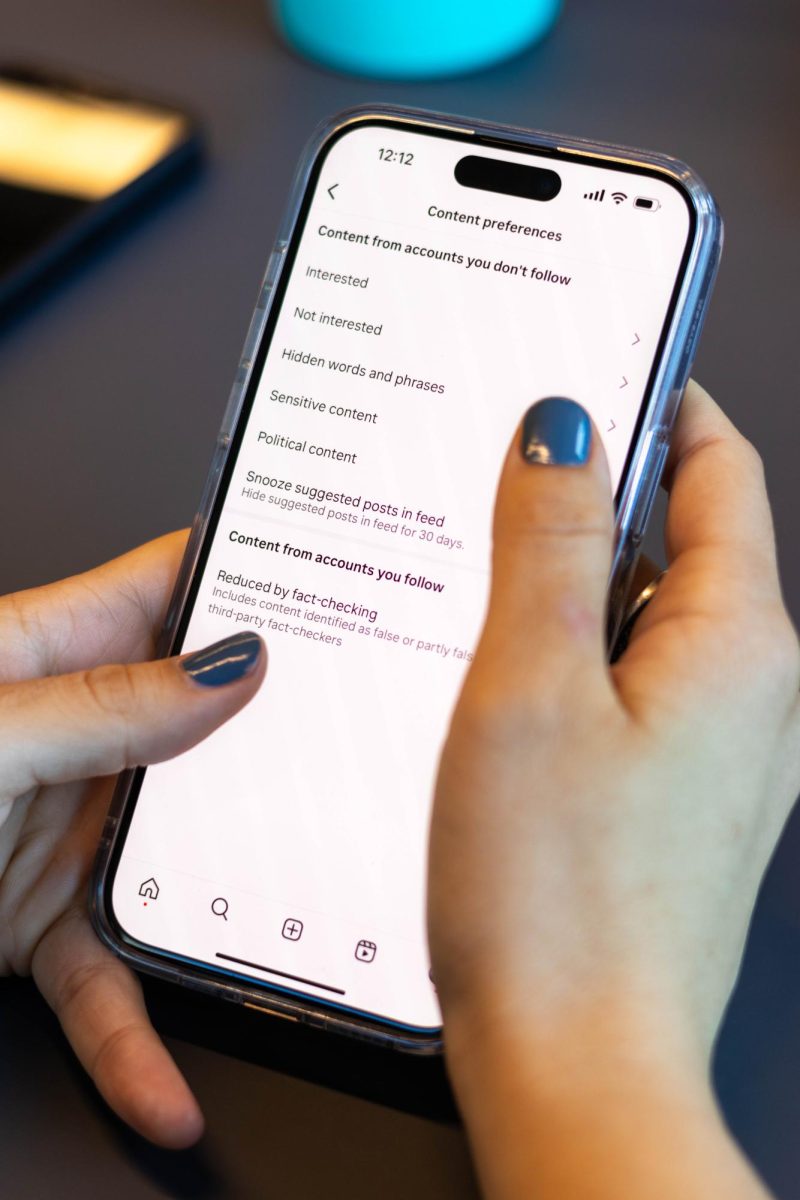

Even when he wasn’t working, Arenas still thought about work and what his next steps in his career should be. When there was no work left to be done at KPMG, Arenas logged onto a website that college students know all too well: LinkedIn.

“I think I do obsess over LinkedIn a lot of the time. I looked at my managers’ when I was on co-op and I tried to mirror their exact path,” Arenas said. “I always compared my path to theirs. There is an obsession of me trying to match my path to that of someone who I know is successful.”

The rise of digital platforms in the 21st century has made it easier for college students to see each other’s accomplishments, compare themselves to one another and feel like they could be doing more.

“It’s a constant cycle. There’s no end to it at all within the logic of the system. So whatever successes one has in that system, it’s never enough,” said Anders Hayden, author of “Sharing the Work, Sparing the Planet.” “You can never sit still. You can never say, ‘Now that I’ve achieved something, I’m going to enjoy those achievements.’ You’ve got to keep up with the competitive pressures.”

Today’s digital platforms have erased the “work hard, play hard” attitude among students because productivity is valued and leisure is not. Many college students are left feeling like there is always something more that they can be doing, no matter how much is on their plate.

Working at a “Big Four” accounting firm, holding executive board positions in clubs, assisting a professor as a teaching assistant and participating in a club sport at just 20 years old, Arenas may be envied by others. But to him, his LinkedIn page does not live up quite to the same standards that he holds of his senior associates.

“There’s always that aspect of, ‘Am I doing enough?’” Arenas said.

THE DIGITAL AGE

There simply is not enough time in a day. Between classes, extracurriculars and co-op searches, Northeastern students are constantly on the move, rarely resting.

And when opportunities for rest come, they do not feel relaxed, they feel uncomfortable.

“Our leisure time is becoming increasingly [colonized],” said John de Graaf, author of “Take Back Your Time.” “Where we once had free time, [we would] want to go for a walk and do simple things like that. Now our free time is spent consuming.”

With the increased popularity of digital platforms and technology, internalized capitalism is an epidemic. Many factors can contribute to this phenomenon, including an individual’s race, religion, cultural beliefs or family values. The overarching factor, however, is systemic.

Internalized capitalism is rooted in white supremacy, said Nikita Banks, a therapist based in Brooklyn, New York.

“I think a lot of what white supremacy … has done is make people of color feel that if they’re not working towards their goal or the goal of their bosses, then they’re lazy,” Banks said.

Banks has dealt with many patients suffering from internalized capitalism. A common trend she found was that these issues can stem from “internal family social pressures,” especially among those who have immigrant parents.

This was true for Maisha Foyez, a second-year cell and molecular biology major, whose parents immigrated from Bangladesh.

“I grew up watching my parents work incredibly hard for what they have. So now if I don’t work hard, I feel like I wasted their sacrifice they made to come here,” Foyez said.

When she isn’t doing work, she spends her leisure time keeping up with her peers’ professional progress.

“I definitely compare myself a lot to people on LinkedIn,” Foyez said. “If I see someone doing something I haven’t considered doing — let’s say they got a volunteering position at a hospital, I would consider applying to it the next day. I don’t have the time for something like that but I feel this sense of needing to compete with them all the time.”

An explanation to why many people, like Foyez, spend their free time thinking about work is because companies today are catering to individuals’ “leisure time” online to promote more consumption, de Graaf said.

“Increasingly, colonization takes place through the use of images and advertising and such, especially in [this] digital world,” de Graaf said.

Whether it be through sponsored advertisements of products or through platforms promoting productivity comparison — like LinkedIn — consumers are encouraged to follow the “I am what I own” and “I am what I produce” mindset.

Somewhere along the way of evolving the typical workspace from factories to the digital world, the “fight for time” for the eight-hour work day eventually became counterproductive. There is no longer a specific time set for work or play. It is instilled in many people, especially college students like Foyez, to be productive during all waking hours of the day.

“I like to stay busy,” Foyez said. “I don’t even know if I like it. I just do it because I feel like I have to.”

LOOKING FORWARD

JoJo D’Amato, a second-year mechanical engineering and design combined major, wanted to take advantage of a university-wide holiday when all classes were canceled. After all, the opportunity to avoid work on a weekday did not come around very often this semester.

D’Amato wanted to take a day to relax, but how could they relax when they hadn’t checked anything off their “to-do” list?

“Those days, I just feel so bad,” D’Amato said. “I shouldn’t have napped for an hour. I shouldn’t have spent so much time watching TikTok. I shouldn’t have spent so much time talking on the phone with my friend. I should have left lunch earlier to just do more work.”

D’Amato felt like they “wasted” their time. They’re not the only one.

The issue of internalized capitalism spreads beyond college students. It has worsened in the last few years with the introduction of digital platforms where every tracked progress on social media platforms is relative. People only share their best moments on social media, which encourages individuals to compare their professional and personal progress to their peers’. Today, psychologists, experts and researchers are coming together to fight the epidemic of internalized capitalism.

Marvin Toliver, a therapist from Philadelphia, deals with patients like D’Amato all the time. In an effort to help individuals recover from issues that stem from internalized capitalism — including depression, anxiety and burnout — Toliver tells his patients to be kinder to themselves. Especially with college students juggling classes, work and social lives, rest is important, Toliver said.

“We have to recognize that our bodies aren’t built to do all these things,” Toliver said. “Our bodies weren’t created to work 40 [or] 50 hours a week. We have to remember that this lifestyle was created by people.”

In looking forward to living a life free of guilt, people who have internalized capitalism should seek help in order to avoid long-term psychological difficulties. There should be no shame in talking to friends, family and therapists because every person has needed some type of help to get to where they are today, Toliver said.

Although it is important for individuals to seek help to change their “I am what I produce” mindset, it is equally as important to reform the roots of where this mindset stems: the work field.

In 2020, the Economic Policy Institute estimated that CEOs in the top 350 firms in the United States were paid 351 times more than the typical worker. Because of this high pay, those entering the workforce are encouraged to strive toward more “successful” jobs like CEOs and entrepreneurs.

Although their work is valuable, de Graaf said that there are many people who provide important amenities with lower pay, such as those in the service sector.

“We need to analyze which jobs are really worthwhile,” de Graaf said. “How do we pay people fairly? How do we break down the gaps in these companies where the CEO makes 400 times as much as the average worker?”

In addition to wealth distribution inequality, the 40-hour work week promotes an unhealthy work-life balance. One of the many solutions to decreasing rates of depression and anxiety in the United States is continuing the three-centuries-long fight for work time reduction, experts say. Activists, such as de Graaf, are still in the “fight for time.” He believes that the goal of America’s economy should be the well-being of the people.

Anders Hayden, author of “Sharing the Work, Sparing the Planet,” agreed and said that an “alternative vision of well-being” is less work time.

“Reduced work time is an option that can expand free time for people so that they can improve quality of life as an alternative to endless growth of production and consumption,” said Hayden, also a professor at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, Canada.

It’s easy to talk, but it’s harder to take action, which is why this conversation should move beyond internalized changes in mindset to legislative reforms, said Nichole Shippen, author of “Decolonizing Time.”

In 2014, de Graaf and Shippen worked together on a campaign called, “Take Back Your Time,” focused on eliminating the epidemic of overwork. To fight for the well-being of overworked Americans, Shippen points out that there should be legislative reforms and improvement for paid parental leave, vacation time and time to take off work to prioritize physical and mental health.

“I think the whole work-life balance model is a bunch of b*******,” Shippen said. “You can’t do it if you don’t fight capitalism.”