By Jenna Majeski, news correspondent

Hundreds of medical professionals, policymakers and community members gathered from across Greater Boston to discuss the opioid epidemic with the U.S. surgeon general and the commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health on the opioid epidemic at the Boston University School of Public Health Jan. 25.

The opioid epidemic is a challenge facing communities across the country, including Boston, where organizations and leaders constantly work to lessen the crisis. As the “nation’s doctor,” U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams is a leader in the mission to combat opioid addiction.

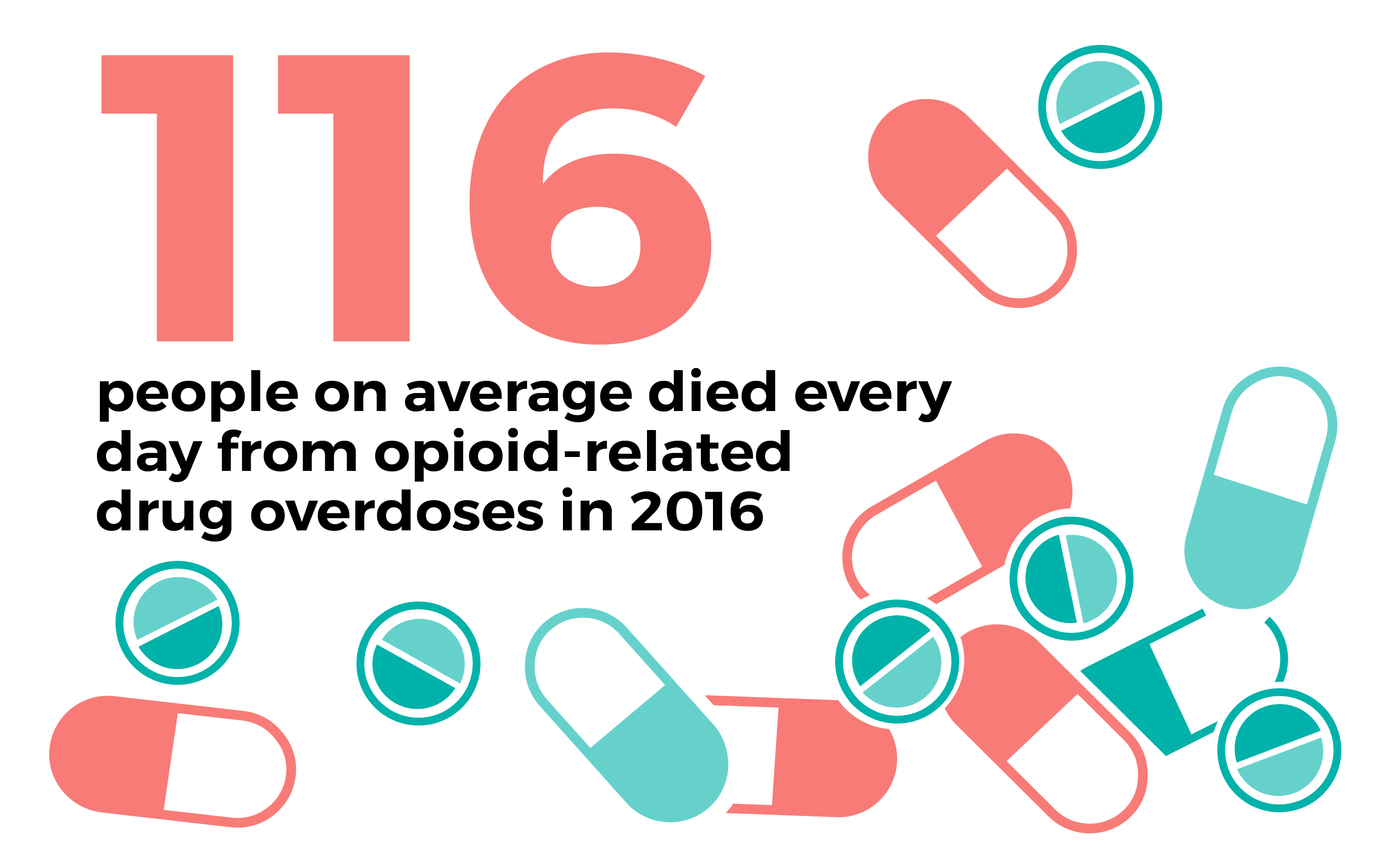

Though conditions are improving, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reports that an average of 116 people died every day in 2016 from opioid-related drug overdoses, including six in Massachusetts. Monica Bharel, the commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, said a death rate this high has not been seen for one cause of death since the beginning of the HIV crisis.

Adams described the individual impact of this epidemic by telling the story of his brother, who has struggled with addiction for many years. Adams detailed the burden of this disease by mentioning the constant state of worry his family endured.

“I share this story, as painful as it is, because it’s important that we understand that addiction touches each and every one of us, that no one is spared,” Adams said. “I want you to know that solving this epidemic is not just pressing; for me, it’s personal.”

Adams and Bharel broke the process of ending the epidemic down into four steps: prevention, intervention, treatment and recovery. Bharel’s team came up with an action plan in 2015 to execute these steps, which they’ve been implementing across Massachusetts ever since.

“In Massachusetts and across the country, because of the wide expanse of this current opiate epidemic, we really have a call to action that goes beyond the medical community, beyond the health care community, beyond public health, to law enforcement, to education, to communities, to people in chronic pain all looking to contribute to the solution,” Bharel said.

This problem is not new, but after decades of continued substance abuse and overdoses it is clear that the opioid epidemic is not going away.

“Why now? There’s a lot of reasons,” Bharel said. “Part of the reason is we should’ve done more. There should’ve been more done in the 1980s, there should’ve been more done in the 1990s, but we’re here now.”

The plan to decrease opiate abuse includes a wide spectrum of changes, ranging from increases in basic education and prevention to larger systematic changes.

Another aspect of the plan is getting those affected by substance use disorder into a streamlined and researched health system.

“Every nonfatal overdose, we are seeing as an opportunity now to get somebody into [the] continuum of care,” said Arlington, Massachusetts, Police Chief Fred Ryan, another panelist at the event.

Adams explained that this continuum starts with Naloxone, a medication sold under the brand name Narcan that is used to reverse the effects of opioids and treat overdoses. Adams and Bharel demonstrated the ease with which one can administer a simple nasal spray of Naloxone. In Massachusetts, Narcan can be purchased in pharmacies and does not require a prescription.

“Massachusetts was one of the first states to have Naloxone available to family and friends,” Bharel said. “Now we have extensive access to Naloxone for bystanders, family and friends.”

Adams described an event earlier that day in Boston in which someone was experiencing an overdose and, though the first responders weren’t carrying Naloxone, a bystander had the medication on him and was able to administer it.

Under an order by Mayor Martin J. Walsh, Boston, among other towns in Massachusetts, is starting to equip first responders with medicines like Naloxone.

Bharel said another important aspect of ending the opioid epidemic is tackling the stigma surrounding substance use disorders.

“Still far too many people than I would imagine think of substance use disorder, this medical disease, as a choice or a moral decision or something somebody could’ve avoided if they tried harder,” Bharel said.

Part of the solution is letting people see successful recovery, but for that to happen there have to be strong recovery programs, Adams said.

“I continue to hear frustration over lack of treatment options and concern over what are good treatment options,” Adams said.

Adams said good recovery programs are three-pronged: They are personalized, they include FDA-approved treatment options and they have a full expanse of recovery support including behavioral treatment, job assistance and housing.

“Folks aren’t going to be able to stay in recovery if they’re worried about where they’re going to live, where they’re going to sleep, how they’re going to eat, if they can pay the bills,” Adams said. “I want all of you to understand how important housing is. One of the number one predictors of success in recovery is if one has stable housing.”

Additionally, much of the solution comes from changing how law enforcement views and interacts with those affected by substance use disorder. This begins with starting a dialogue, Ryan said.

“We held a conference here [and] we had over 300 law enforcement officials from around the country and we had a panel of medical doctors talking about medication-assisted treatment options with cops,” Ryan said.

Ryan said dialogues like this help make real change within the opioid crisis because they take various sides of the issue into account and make room for change.

“We’ve done a lot of work around the country, particularly here in the commonwealth with the commissioner and the governor, around changing the conversation from one of arrest and incarceration to treatment and prevention,” Ryan said.

With developments in communication and science, the medical community has been able to learn much about the opioid crisis, even identifying specific groups of people that are more at risk for opioid addictions. These include people recently released from incarceration or experiencing homelessness, postpartum women and those with severe mental illness.

Yet there is still much to be learned about this issue.

“We know about medication but we don’t know what treatment path is best for what kind of person. We have lots of questions to answer and lots of data that can get at those answers,” Bharel said. “Think about something like cardiovascular disease and how much we know about it and how little we know about substance use disorders.”

Overdoses are decreasing and outlooks are brighter, but work still needs to be done in terms of being more vigilant about preventing dealers from targeting vulnerable areas, such as outside hospitals and jails.

“We’ve got to make it easier to get help than it is to get high,” Adams said.

Adams said those who aren’t directly affected by substance use disorder cannot simply ignore the problem.

“It’s not your problem, it’s our problem. And it’s not up to me to come up with a solution, it’s up to all of us to come up with a solution,” Adams said. “And I’m convinced that if we all leave this room committing to do that, we will solve this opioid epidemic. And not only will we solve the opioid epidemic, but we’ll deal with some of the proximate causes that help make us a healthier society in the long run.”