By Ava Sasani, news staff

Ana, a custodian at Harvard University and mother to a teenager in Boston Public Schools, has 16 months left in the United States. After September 2019, Ana and approximately 200,000 other Salvadorians will lose the documentation that has allowed them to live and work in the United States for 17 years.

“Of course I’m worried,” said Ana, whose name has been altered to protect her privacy.

Temporary Protected Status, or TPS, is a humanitarian immigration program extended to the people of El Salvador after the country suffered a catastrophic earthquake in 2001. In January, President Donald J. Trump announced the end of the TPS provision to Salvadorians, giving them 18 months to exit the country before their legal immigration status is revoked.

Ana and her daughter attended a protest Tuesday organized by professors of the Harvard Divinity School. Students, faculty and staff of Harvard and MIT stood in front of Boston’s U.S. Immigration Courts at the JFK Federal Building, protesting the Trump administration’s new immigration orders.

Walking through Boston’s City Hall Plaza, Ana says she takes some comfort in these demonstrations as she fights a tiresome battle for permanent residence.

“Teachers organized this, the community is starting to support us in this struggle, so it gives me hope to continue [to] fight,” Ana said.

Harvard Divinity School professor Ahmed Ragab is one of the educators who organized Tuesday’s protests. Ragab hopes universities across Boston will actively help combat the deportation of their students, faculty and service staff members, including custodial staff like Ana.

“As faculty we are in a very privileged position,” Ragab said. “We want to use this privilege to amplify the voices of those who can’t speak as loudly as we can.”

As the protest crowd gradually swells, Ragab leads them in a chant of “This is what America looks like.” Born and raised in Egypt, Ragab became a naturalized U.S. citizen in September 2017. That same month, Trump moved to suspend the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals immigration program, or DACA, which had prevented the deportation of children who arrived in the United States before the age of sixteen.

Since then, Ragab and other Harvard faculty members and students have organized events to protest the Trump administration’s restrictive immigration policies. On Tuesday, standing outside the same building that houses the offices of Massachusetts Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Ed Markey, Ragab and his fellow organizers hoped their demonstration would raise awareness to the urgency of the TPS revocation.

“I believe all schools should hold events like this and spread awareness on questions of immigration,” Ragab said. “If we hope to make the trainings of our students relevant for this world, we need to engage with the issues of this world, and obviously immigration is a central issue.”

Many of Ragab’s colleagues joined the protest, largely because of first-hand exposure to the stresses of immigration. One of the first protesters to arrive at the plaza was Emily Click, a lecturer and assistant dean at Harvard Divinity School.

“Any students who may be here from El Salvador may have parents who are being deported, they might have been brought here when they were children. A lot of them were born here but their parents weren’t born here, so they’re tearing apart families,” said Click. “There are a lot of people with a lot of worries at school.”

As the crowd of protesters gradually dispersed to write letters to Warren and Markey, many of Ragab’s students acknowledged the privilege that white Harvard students retain over immigrants.

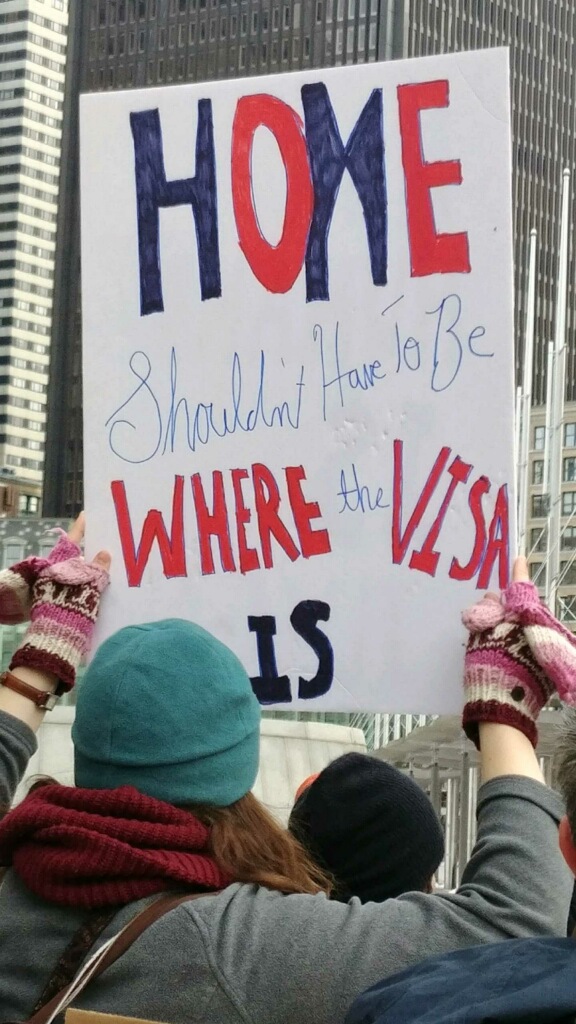

Kat Poje, a graduate student at the Harvard Divinity School, carries a sign that reads “home shouldn’t have to be where the visa is.” Poje said she attended the protest because she is frustrated with the Trump administration’s immigration objectives, which she said have been prejudiced against people from other countries.

“I’m a student … and my life has been shaped by the education that I’ve been privileged to have here,” said Poje. “The thought that my classmates, my teachers, the people that run my schools, are being threatened to be taken away from what is their home as much as my home is really why I’m here.”