By Tessa Witter, news correspondent

On Hanover Street in the North End, the heady smells of pasta, pastries and sauces lead many into restaurants and cafes with Italian flags, friendly chatter and music. Tourists pose, take pictures and point at historical sites. Locals pass them as they go about their daily lives, dodging a crowd of college students waiting outside a restaurant.

Through festivals, music and food, the North End maintains its identity as a “Little Italy.” Rose-Marie Gomez, branding and marketing manager of the North End Music and Performing Arts Center, or NEMPAC, said the North End is a neighborhood that tries very hard to keep its Italian heritage.

“I think when you step into the North End, you step into this little world of protected Italian culture. So you have a mixture of the old Italians, like the first families,” said Gomez. “Then you have the new North Enders – the new families that also bring a different structure.”

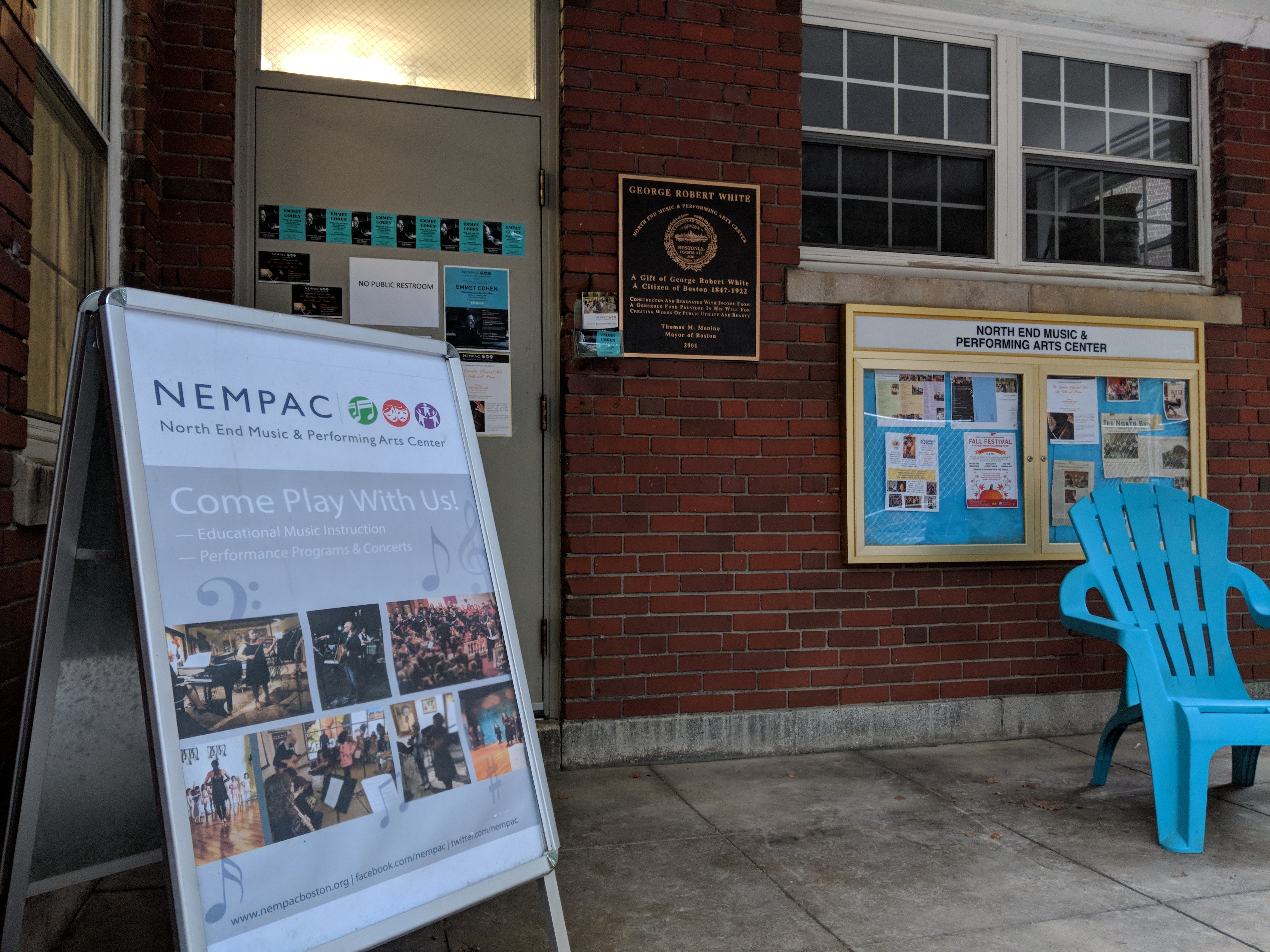

NEMPAC is a community group that works to offer music, culture and performing arts to surrounding neighborhoods. While producing many programs and events with various composers of diverse backgrounds, it does work to cater to the North End Italian community, Gomez said.

The North End is unique because it has maintained its Italian culture for about 10 to 15 years longer than other “Little Italies,” according to Jerome Krase, a professor at Brooklyn College of the City University of New York. He conducted a study on “Little Italies” across the United States and abroad, including Boston’s North End.

Krase said the neighborhood has endured as a “Little Italy” because the Central Artery of Interstate 93 isolated the North End from the rest of the city, and Italians have a cultural mentality of never moving. Those Italians who moved settled in the North End because it was familiar and a safe place with other Italians in the neighborhood.

Before the Italians arrived to the North End in the late 1800s and early 1900s, the neighborhood was filled with Jewish and Irish residents. Eventually, many of the Jews and Irish moved away, leaving a neighborhood of mostly Italians.

Rita Pagliuca, a lifetime resident of the North End, said when she was a kid, the Italians embraced the Irish and Jewish culture because “that’s what Italians do.” After those groups migrated out, the Italians became very sheltered and protected, Pagliuca said. She and her friends only did things the Italian way, which fostered a bit of an exclusionary mentality.

When people of other cultures started to move into the North End during the 1970s, Pagliuca said there was some resistance. When the stretch of I-93 near the North End was turned into a tunnel during the 2000s, it further opened up the neighborhood to the rest of Boston, leading to an additional influx of new families.

Now, millenials are starting to move into the neighborhood, Pagliuca said, and many Italians who were here before these transitions want it back to the way it was – when there were more Italians in the neighborhood. She said she’s an advocate of embracing her new, younger and more diverse neighbors.

“Young couples are moving in with their kids. They’re not necessarily Italian, but they’re family,” Pagliuca said. “A lot of us have embraced that.”

In his study, Krase characterized the North End as having a “split personality.” There is a commercial space with lots of restaurants and cafes with Italian names, most of which are new in comparison to how old the neighborhood actually is.

Parallel to this tourist-oriented North End is the actual neighborhood, which has ordinary people going about their daily lives. James Pasto, a professor at Boston University and a North End native, said these two worlds occupy the same space and intersect all the time – like a Northeastern University student coming to a neighborhood cafe and having a conversation with a North End native.

Alex Goldfeld, co-founder and president of the North End Historical Society, said though he is a non-Italian and non-native resident he probably knows almost everybody in the neighborhood. The North End Historical Society, founded nine years ago, works to preserve the neighborhood and its history through public programs and research.

Goldfeld felt there was a need to record the history of the North End, with a focus on its Italian heritage, because the neighborhood’s rich history fascinates him. He also said Italian history tends to be understudied.

“There’s so many opportunities around every corner to learn something new,” Goldfeld said. “I love Boston, but the North End is obviously always going to be my favorite.”

At the corner of Salem Street is Bova’s Bakery, which was founded in 1926 by Antonio Bova after he came to the United States from Italy.

Vicky Bova-Kluse, Antonio Bova’s granddaughter, said the bakery changes with the times. Years ago, the bakery sold thousands of loaves of bread, but today many consumers are gluten free or don’t even want bread with their meals, Bova-Kluse said.

“We still have the cannolis that are authentic,” said Bova-Kluse. “But a lot of the stuff, a lot of it is Americanized. Made by Italians, though, but it’s Americanized.”

People of Italian descent make up less than a third of the North End population, Pasto said. However, he said there should be a distinction between the old-time North Enders who are of Italian descent and have lived there their whole lives, and the new families that have moved in, but consider themselves Italian-Americans.

Krase believes the Italians and Italian Americans — the new and the old — will change with the times and become more Americanized. Though they are not doing stereotypical Italian things, their way of life is no less authentically Italian, said Krase. It’s just their new way of life.

In the future, the North End’s Italian authenticity will fade, mostly due to the growing diversity of the neighborhood, Pasto said.

“The people keep the memory and the activity alive,” Pasto said. “Eventually, you know, they’ll be all gone, it’s just store-fronts and restaurants and stories about the past.”