By Jacob Horowitz, sports columnist

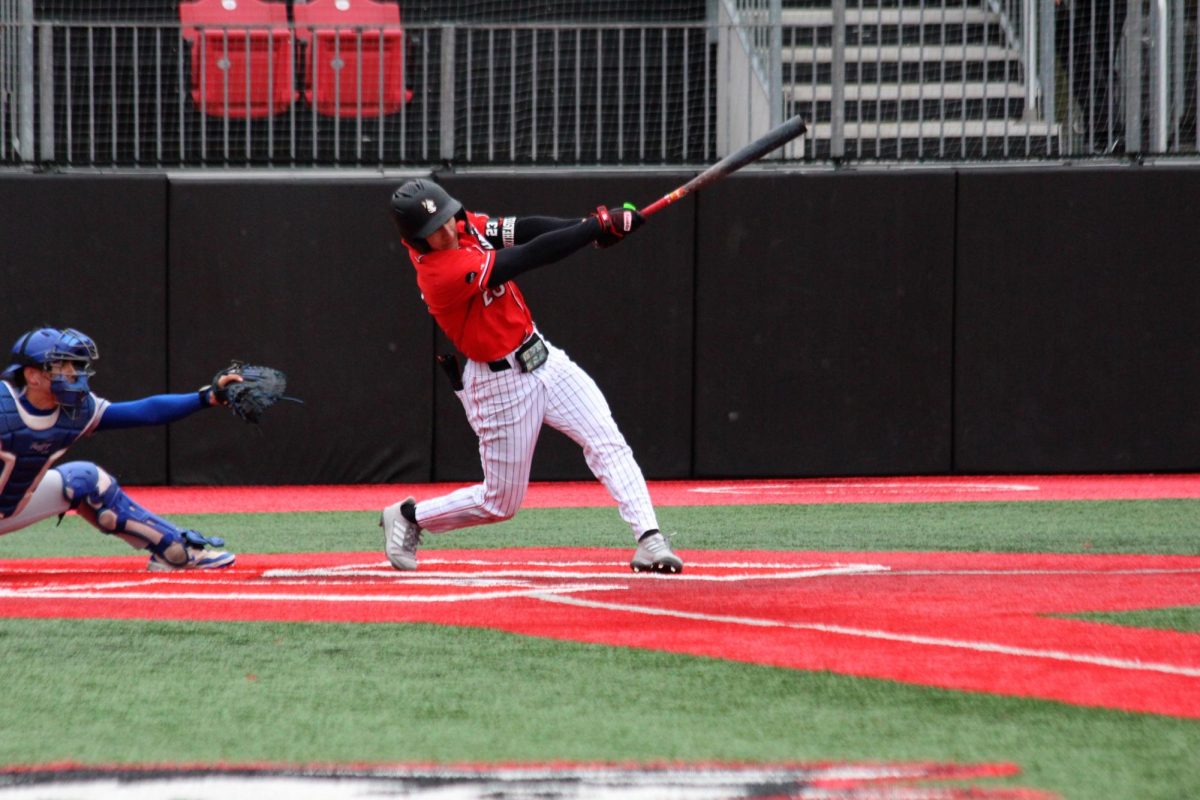

New York Yankees pitcher Masahiro Tanaka winds up, loading energy onto his back leg before rocketing forward, his whole body working in unison as he slings the ball towards Boston’s Xander Bogaerts.

Bogaerts swings; contact.

The ball takes off toward the centerfield bleachers. A few lose sight but it doesn’t matter — there’s safety in numbers. Everyone else can see it and they know its destination.

The cheering intensifies as the ball hovers above deep centerfield, now a clear home run. It’s difficult to describe how cheering works at a ballpark. It’s not a wave since there is no ebb and flow; it hits all at once.

But I didn’t see it happen. I was getting ice cream. That was the only Red Sox home run during my first time at Fenway Park. They lost, an inevitability visible as early as the sixth inning.

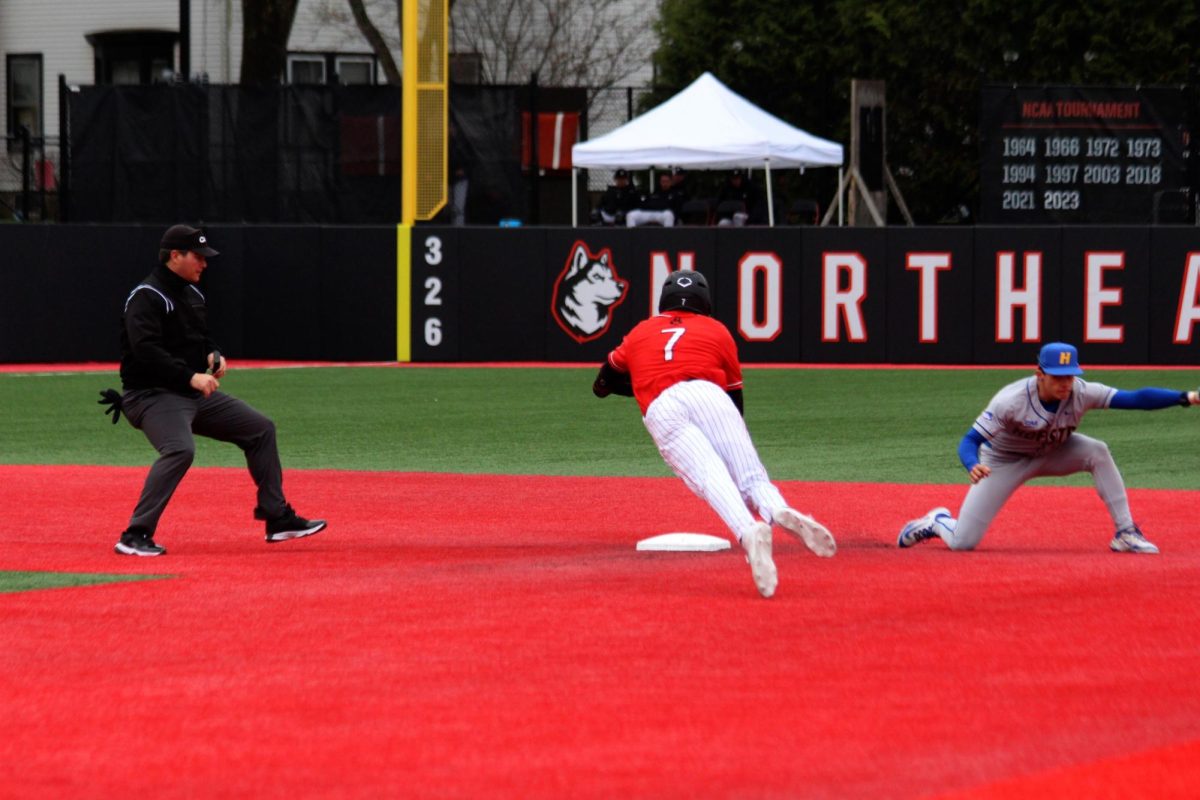

Live baseball is a delicate balance between crowd and players; a give and take of drama and cheer. I arrived at Fenway expecting a ratio similar to what I’m used to at Washington Nationals games. Instead, I experienced a game defined less on the field and more in the raucous, rivalry-fueled centerfield bleachers.

Early on, a middle-aged man threw peanuts at the Yankees fans in front of him. After the storm of nuts, the wrong man was blamed, an innocent bystander eating his own peanuts. A shouting match began, drawing the attention of more Boston fans, who began to throw their nuts. I watched the whole conflict rapt, forgetting I was at a baseball game. I’d never seen such animated nut throwing. Pitch after my pitch, my stare wasn’t broken until a woman stepped in and made both parties drunkenly apologize. Despite playoff baseball being played right before my eyes, I was distracted by fellow spectators in the centerfield bleachers. The rivalry infused crowd was becoming more than the game itself.

As a loss became more likely and the energy left the field, the live baseball balance began to tip even more towards the spectators. Many fans gave up on arguing, turning to antics and absurdity to pass the time. A drunk college student in my row called over to a man selling water bottles. Quickly forking over $100 and buying the entire case of water, he had the entire bleacher’s attention. After lobbing bottles around the section, he was down to the last one. He faced away from the field, making eye contact with a 20-something standing up. In sync, they pointed at each other and began wildly screaming about the last bottle. In a perfect, Tom Brady-esque arc the one threw the bottle and the other caught and chugged it in the blink of an eye. It felt theatrical, almost scripted. It was as if the buyer and the chugger worked for the park, sleeper cells planted and activated in case of a bad game.

After the peanut storm and water buyout, the stalling game and impending Boston loss seemed peripheral. I scanned the crowd looking for more drama but was interrupted by my worried friend sitting next to me. A drunk man to his right, at least five beers in, began to hiccup profusely. He slumped back in his chair. Vomit was coming. But instead of reaching for water, he chose to drink more beer. Miraculously, this did the trick. I was relieved; not just for my friend but for the sick stranger as well. He was part of our bleacher section: the most important aspect of this rivalry and Fenway Park. We were comrades now.

When the Yankees come to Fenway, there is a different breed of live baseball. The balance between sport and spectator begins tilted towards the enthused fans and, if the Red Sox start losing, can lurch further towards the bleachers. While the stadium and rivalry are centered purely towards baseball, it’s easy to lose sight of the sport as a spectator. The people of Fenway provide if the baseball doesn’t. Their enthusiasm and revelry can’t be found anywhere else. Nationals Park now seems tame. There, a baseball game is about baseball and not much else. At Fenway, it’s about so much more.