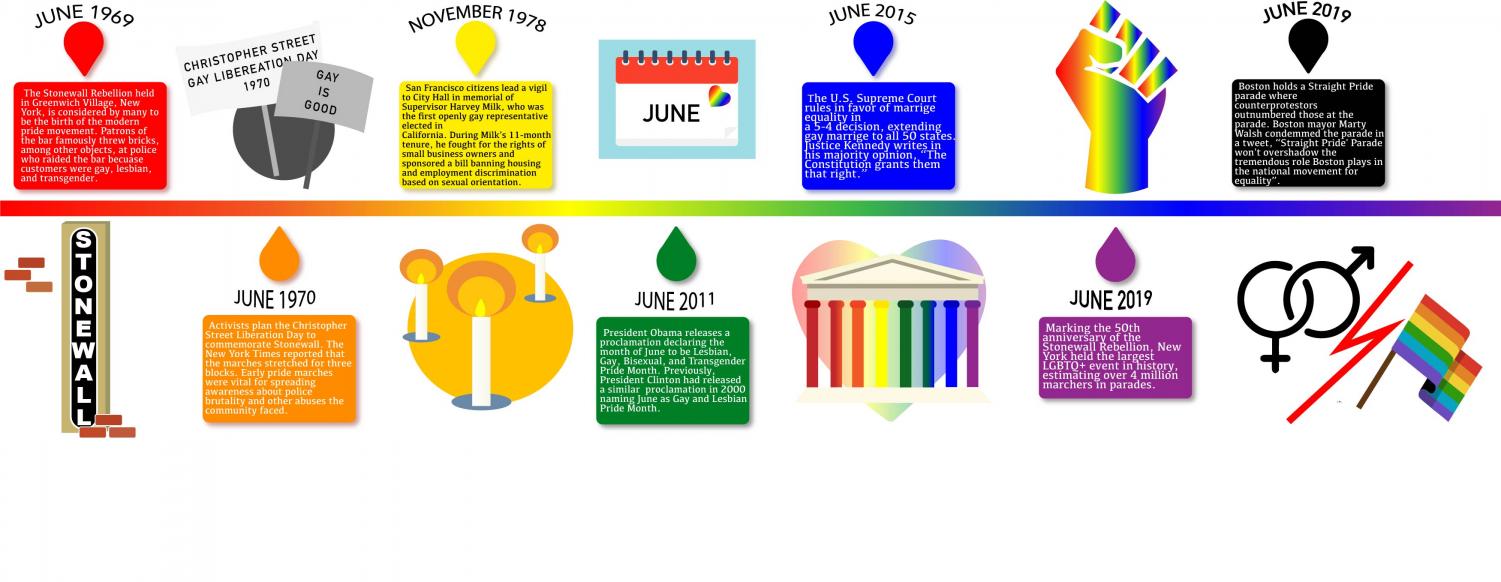

Political polarization at the center of “Straight Pride Parade”

A “2020 Trump” float passes through the parade route Aug. 31.

September 25, 2019

The controversial “Straight Pride Parade” drew roughly 200 participants to Boston Aug. 31. A majority of the attendees came to back Super Happy Fun America, or SHFA, a group that describes themselves as “advocates for the straight community.”

Many marchers decked themselves out in Trump apparel, waved American flags, and held signs with statements such as “Straight Lives Matter” and “It’s Great to Be Straight.” A counter-protest, which drew nearly 600 people, met the participants with strong opposition.

Boston Police arrested 36 people on a variety of charges, including assault and battery on police officers. Suffolk County District Attorney Rachael Rollins asked for the charges to be dropped against protesters with minor offenses.

Sky Bauer, a second-year psychology major at Northeastern, initially did not believe the parade would even happen. However, the issue hit close to home for Bauer, who is the secretary of NUPride and has witnessed close friends be disparaged because of their sexuality.

“When I first heard about it, I wasn’t concerned about it all. There is no way this is real,” Bauer said.

Soon after, though, Bauer worried that members of SHFA had potential ties to the alt-right and became concerned that the parade might become “the next Charlotesville,” referencing the white supremacist rally Unite the Right that ended in the death of 32-year-old Heather Heyer.

The president of SHFA, John Hugo, led an unsuccessful campaign for Massachusetts’ 5th Congressional District back in 2018 which was endorsed by Resist Marxism, the group that organized the Unite the Right rally. The vice president of the organization, Mark Sahady, who has been linked to the Massachusetts Patriot Front as well as the New Hampshire American Guard, gained attention on social media after being videotaped grabbing a transgender woman at the Boston Women’s March this year.

Bauer said this incident became their incentive to participate in the counter-protest.

“It was not about sexuality at all,” Bauer said. “There was a big float with ‘Trump 2020’ coming down. It was an alt-right rally disguised with pride.”

For Bauer, the Trump administration seemed to be a key-player in the origins of the parade.

“It’s underground racists that have recently come to light under Trump’s administration,” Bauer said. “Now that they think they have [a] voice under Trump, they also think they have the right to say they have hate against everyone who isn’t a WASP.”

While the marchers mocked political correctness, the counter-protestors poked fun at Trump’s language. Bauer recalls a sign that read, “World’s Tiniest Parade. Sad.”

If given another opportunity to speak face to face with a participant, Bauer said they would have asked them, “Where have you been oppressed? When has being heterosexual caused you pain?”

Bauer said LGBTQ+ allies will “step back and let LBGTQ+ people speak up about their oppression as well as understand that straight people do not face the same oppression as LGBTQ+ people, if at all.”

Kara Rofé, a fourth-year health science major at Northeastern, was in Copley Square when she saw parade participants begin to arrive. She said she attempted to initiate conversation with two of the parade organizers, but they appeared busy and were unresponsive.

“They were very passive aggressive. They didn’t really want to speak to me,” Rofé said. “They didn’t really care about the people outside of the gates.”

Rofé initially saw posts about the parade on social media and thought it was “just a joke.”

She called the event “an underlying pro-Trump rally” and believes most participants came to the parade for attention.

“I think they believe that queer people are being labeled as ‘special’ or ‘different,’ and they are like, ‘why not us?’ and, ‘why don’t we get the same attention?’” Rofé said.

Rofé thinks participants might have been poking fun at political correctness and the liberal views of Democratic presidential candidates such as Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren.

She recalls a person dressed up as a clown who held a sign asking for clown rights, too.

“I don’t know if I saw any alt-right members. I know some people said they saw Nazis. I didn’t really see any of that,” Rofé said, “I think it was more of pushing people’s buttons.”

Chris Crowley, a 52-year-old lawyer who hails from Florida and previously served in the army, came to Boston to support the parade for a couple of reasons.

“With every person it was different. For me it was just kind of mocking political correctness,” Crowley said. “You know, because you have Black Lives Matter and you have pride day.”

Crowley said the idea for the parade began after Mark Sahady was barred from raising a straight pride flag at Boston’s City Hall. Crowley defended Sahady, saying, “Well, it’s not that offensive, but it depends on who you talk to, because everything is offensive.”

“Hyper-political sensitivity” is a major issue for Crowley, who said he believed the media mischaracterized those who marched in the parade.

“What I constantly heard from, no offense, but liberal journalists, and liberals and counter-protests, was ‘white-supremacy,’” Crowley said.

Crowley spoke about the racial diversity of the speakers invited to the parade, saying, “Four or five of the eight or nine speakers were African American but the Boston Globe kept referring to us as white supremacists.”

The present speakers included SHFA leaders Mark Sahady and John Hugo, as well as far-right political commentator Milo Yiannopoulos. Five African American speakers also attended the event, including YouTube personality The Amazing Lucas and musical artist G.Notes Justice, who led the audience in the “Straight Pride Song.”

“The counter protesters kept saying, ‘racists,’ and I don’t get it,” Crowley said. “It did not make logical sense, but not much of what the counter protesters said did. I saw about a thousand middle fingers and most of us just waved back to them.”

However, Crowley also said he doesn’t stand by SHFA on everything. What he calls the “activist agenda” is one area where he splits from the group. Crowley recalls a speaker at the parade who encouraged promoting a “normal lifestyle” in grade schools.

“I don’t think we should invite in some Southern Baptist preacher to say ‘homesexuality is a sin’. I don’t think that. I really think schools should focus more on the core mission and less of this social advocacy,” Crowley said.

If given the chance to speak face to face with an LGBTQ+ counter protester, Crowley said he would tell them to “chill out.”

Jonathan Kaufman, the director of the School of Journalism at Northeastern and former writer for the Boston Globe, explained how the execution of the Straight Pride Parade in Boston, one of the most liberal cities in the country, was “politically calculated.”

“If you’re kind of on the outs, and sort of a marginal group, what’s a way to get attention from the media and from others?” Kaufman said. “Go to a liberal place and be very provocative and hope that people will respond to you.”

Kaufman said the media is always struggling with how to characterize things.

“We have to be careful not to conflate legitimate concerns and discussion of certain issues with groups that just want their five minutes in the spotlight,” Kaufman said. “And sometimes, if you deprive them from that and not respond with counter protests and that, I think they just kind of disappear, especially in a place like Massachusetts.”

Kaufman said one of the things President Donald J. Trump has done is make it easier for people to say offensive things in public.

“I think that’s a shame because I think the country was moving, before Trump was elected, to have civility, talk about things in a civil way, and people’s attitudes were changing,” Kaufman said. “And frankly, gay rights is one of the areas where you see the biggest change in recent years.”

Just one year into Trump’s presidency, ideological differences between Republicans and Democrats grew even wider on issues like race, immigration and national security. Today, politicians are tasked with looking for ways to unite the country.

“The genie is out of the bottle,” Kaufman said. “We have to try to make a better effort to listen to each other. That’s going to be a tall order for the next president and certainly if Trump wins I think it will reinforce the belief that saying these things is a winning electoral strategy.”