Nahant residents denounce NU construction on ‘wildlife preserve’

October 10, 2019

In its 1965 proposal for the Marine Science Center at East Point, Nahant, Northeastern pledged to make the tract of land next to the facility a “wildlife preserve.” Now, the university is clearing the foliage to make room for a 55,000-square-foot Coastal Sustainability Institute.

Residents of Nahant fear the addition will disrupt the area’s wildlife and fundamentally alter the laid-back, residential character of the town, which is one of the smallest in Massachusetts.

Nahant Bay is designated as an “important bird area” by Mass Audubon and is a valuable habitat for lobster, flounder and other species of aquatic life, according to a report by the Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act Office.

Linda Pivacek, a 78-year-old wildlife enthusiast and a retired medical professional, said she first discovered Northeastern had begun clearing land for testing in June. She planned to search for confirmation that two state-protected birds sighted at East Point were breeding in the area. Instead of nests and baby birds, Pivacek found a cleared access road and piles of freshly cut wood.

“It had been bulldozed illegally by Northeastern,” she said. “The whole area where the birds were was gone.”

Pivacek and other residents said Northeastern notified the town about testing-related work that would occur June 28, but that university officials had not been clear about the magnitude of damage it would cause.

After hearing about the damage, Kristen Kent, the chairman of Nahant’s conservation commission, issued an enforcement order to Northeastern’s project manager, calling for the university to cease work on the tract of land designated as a “wetland resource area.” Kent said the rest of the damage occurred on land outside of the commission’s jurisdiction.

Workers began clearing the access road to the East Point site on June 28.

In late July, members of the nonprofit Nahant Preservation Trust, or NPT, notified the university of their intent to sue.

NPT argues that the land is zoned as a public park, citing a long history of pledges by university officials to maintain the site as a preserve. The nonprofit is seeking an exception to the Dover Amendment, a Massachusetts law allowing educational institutions and other nonprofits to ignore zoning ordinances.

State Rep. Peter Capano (D-Lynn) said he supports the suit and has pushed for changes to the Dover Amendment that would allow for waivers in cases of potential environmental damage.

While the statute in its current form has done good things for nonprofits in the state, he said, it leaves room for abuse of the environment.

“It’s not right that a billion dollar institution … [is coming] into a place and just [destroying] it, you know, because they can,” Capano said. “Whether it’s Nahant, Lynn or anywhere else, the idea that that could happen to a natural resource area or a wetland is wrong.”

Renata Nyul, a university spokesperson, addressed the lawsuit in an Aug. 26 email to The News.

“On July 23rd, the Nahant Preservation Trust, and 29 residents of Nahant, informed Northeastern of their intent to sue the university to block the proposed expansion of its Marine Science Center, which sits on land Northeastern has owned for more than 50 years,” Nyul said in the email.

Before Nahant residents could legally begin their lawsuit to contest the project, Northeastern filed their own suit in land court Aug. 9.

“To protect its interests, and to minimize protracted and costly litigation, Northeastern is seeking a declaratory judgment in Massachusetts Land Court. While this process takes place, the university will continue to work with town officials to develop a mutually agreeable plan that allows the university to enhance its important coastal sustainability research, while preserving the unique vitality and character of Nahant,” Nyul wrote.

Marilyn Mahoney, 70, a longtime resident of Nahant and a party to NPT’s lawsuit against Northeastern, said she is frustrated by the university’s lack of communication with residents.

“Northeastern had all this stuff in the planning and had never approached the citizens that it was indeed going to impact, which I find appalling,” she said. “I mean, if you’re going to do something to the community that’s going to impact the citizens of the community, they should be part of the process right from day one.”

Residents found out about the project, Mahoney said, after the Marine Science Center filed an application for new seawater pipes in early 2018. When her husband, Bill, investigated and told other residents he’d found orange markers on trees on East Point, she said, over 30 people showed up to the meeting where town officials planned to review the application.

Northeastern officials held public meetings and took comments from residents later that year.

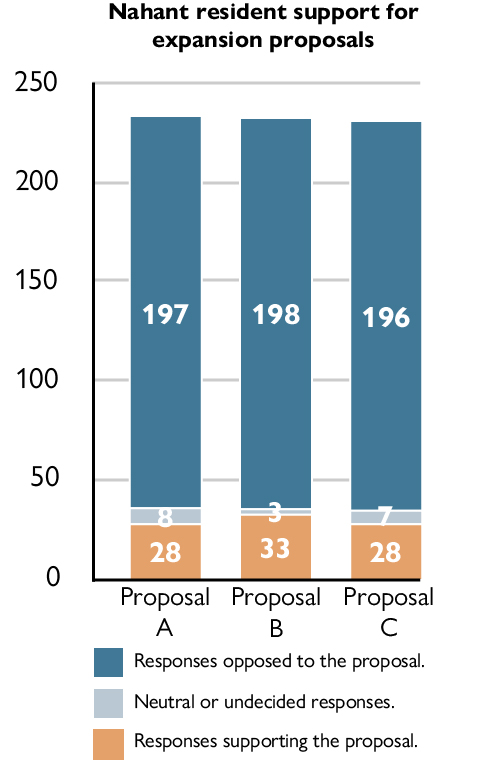

In December, they presented three revised proposals they hoped would better fit the town’s needs. Only 17 percent of residents who responded to a town-commissioned survey supported any of Northeastern’s new plans. The university selected the second of their three plans, which reduced the footprint of the proposed facility from 60,000 to 55,000 square feet.

One alternative Northeastern refused to consider, Capano said, is building the facility on the Lynn waterfront instead of Nahant. He said he would welcome the construction of an academic facility in the area and sees it as a potential “jumping-off point” for further development.

“I had spoken to the economic development director in Lynn, and he said he would roll out the red carpet for Northeastern,” he said. “I spoke at the town hall meeting, and I told [Northeastern] that, but they weren’t interested.”

Capano said university officials told him they preferred to focus on their relationship with Nahant. But beyond the fact that Northeastern already has a facility near East Point, Capano said he thinks the university chose the site for aesthetic reasons.

“It’s like a trophy,” he said. “I mean, why wouldn’t you want to build there? It’s a beautiful spot.”

For Nahant residents — human and otherwise — East Point means more than aesthetics.

Pivacek worries about endangered bird populations in the area. The lights from the facility, which are kept on overnight for security reasons, could cause navigation issues for migrating birds, potentially leading them to their deaths, as the birds get confused when they see a bright light while flying in the dark.

“They don’t know where they’re going,” Pivacek said. “They circle around and around the buildings until they crash into one and die.”

Bill Mahoney, Marilyn Mahoney’s husband and a fourth-generation Nahant lobsterman, said the larger seawater pipes on the new facility could hurt lobster populations. Northeastern has pledged not to use the pipes at their full capacity, but Mahoney worries the university will slowly increase output as outcry about the facility dwindles.

Bill Mahoney stands with NPT member Christian Bauta in front of the Marine Science Center’s seawater outflow pipes.

Residents have similar concerns about the facility’s effect on the character of the town. Joshua Antrim, a 58-year-old Nahant selectman, said he fears the traffic generated by Northeastern will increase. He said he is worried about the impact this might have on the town’s culture.

“There isn’t really any significant business in town,” Antrim said. “There’s, you know, a pizza shop and a couple of restaurants. People aren’t normally commuting to Nahant … So, people that [would be] in town on a daily basis [wouldn’t] necessarily have the same connection to the town and the same, maybe, respect for the neighbors.”

Marilyn Mahoney said she sees the conflict with Northeastern as a problem of respect.

“This community is not for sale,” she said. “Why are the scientists that claim to be environmentalists working to preserve the environment going to rape our Nahant so they can build up a global reputation?”