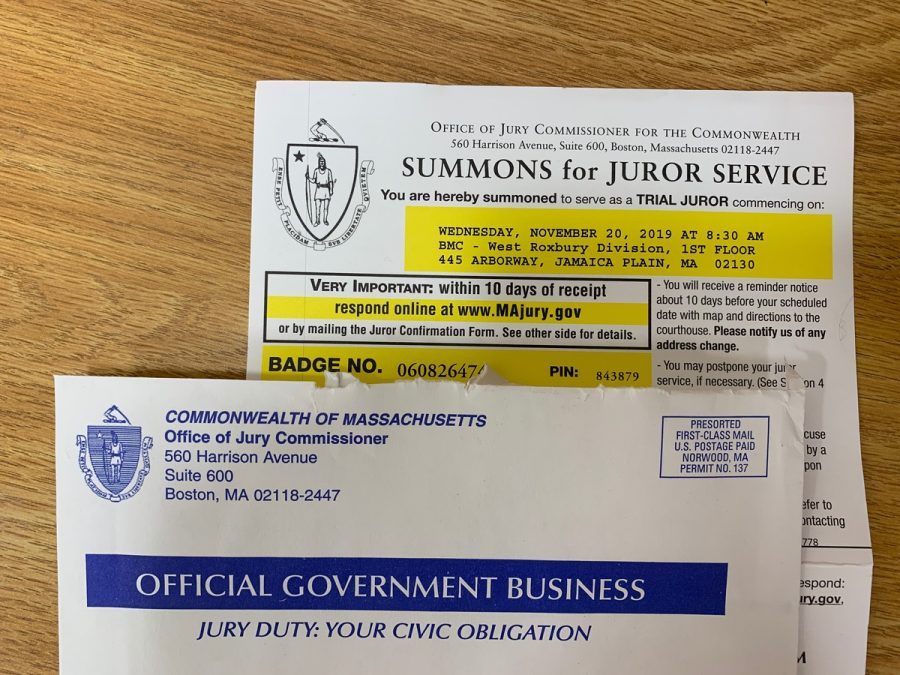

Jury duty surprises students, conflicts with classes

Jury duty can be an inconvenience for students.

October 9, 2019

When the judge called Julia Mannix to the bench during a jury selection, she was asked which university she attended. When she said she went to Northeastern, the judge told her, “For $70,000 a year, you shouldn’t have to miss a day of class.” Mannix, a second-year human services and communications studies major, was dismissed.

Students who hope to avoid being selected to serve on a jury evidently feel the same. Such students include Padraic Burns, a third-year computer and electrical engineering combined major, who was summoned for jury duty last fall. Burns, whose mother is an attorney, said he was educated enough about the process that he found a way to be dismissed.

The jury for the trial Burns was selected for on the day of his summons involved a crime that took place near Ruggles Station, close to where he was living at the time. His proximity to the crime made him ineligible to serve as a juror, and he was dismissed.

Burns said being impaneled and having to attend the trial would have been an inconvenience for him. “It was an inconvenience without being picked,” he said.

The state of Massachusetts compiles a master list of potential jurors every year based on the state’s mandatory annual municipal census. Every city and town in the state takes a census each year, and the results are sent to the jury commissioner. This process creates a larger jury pool than other states, which typically use lists of citizens registered to vote and those with driver’s licenses. In Massachusetts, this list is then split into 14 separate lists, and jurors are randomly selected using the software program Jury+.

Massachusetts also allows students to serve, which is another unique decision that increases the potential jury pool for the state. According to a WGBH article from last year exploring jury selection in the Commonwealth, about 10 percent of the population receives summons every year. Included in that population is the large number of students who attend Massachusetts’ 114 colleges and universities.

Mannix said when she was summoned for jury duty, she was originally interested in the process. That was until she found out the trial she could be chosen for was a medical malpractice case with a scheduled duration of nine days, which would significantly impact her ability to attend classes. Other students in Mannix’s group were panicking about their academic responsibilities as well.

“We had a half-hour break at one point, and another girl was telling me about a test she had that day, and how that break might be what made her late,” said Mannix. Another student from Middlebury College planned to leave for a semester at sea while the trial was scheduled to take place. She was unsure if that was an acceptable excuse and panicked about being impaneled.

Not only can serving jury duty lead to absences from classes, jobs and other responsibilities, but students are also often unaware that it is even a possibility for them to get summoned to serve on a jury as a student or as someone from outside the state.

“Most people were surprised that I had been chosen,” Burns said. He found that other students, especially those who, like him, were from out of state, were confused that they could be summoned in Massachusetts or that students could be summoned at all.

Kiley Sullivan, a second-year criminal justice and political science combined major, said she knew she could potentially be summoned, but noted the confusion of others, including her siblings and friends in other states, such as her home state of New Hampshire.

“The college should do a better job of letting students know they’re eligible because plenty of students don’t check their mailboxes and don’t get notified,” she said. Sullivan said she remembers when she received her summons last fall and saw notices on a few mailboxes for students who had also received summons, but did not check their mailboxes.

Burns also believes either the city or the state should notify students, particularly those from out of state, that they have the potential to be summoned once they become residents.

Sullivan was dismissed, as were Mannix and Burns. Burns said he has not met a student who actually ended up being impaneled on a jury, suggesting most students find a way to avoid it or are dismissed by the judge or attorneys involved in the case.

Northeastern professor of criminal justice and defense attorney Krista Larsen says a lot of jury selection, beyond the random selection from the population, comes down to the case and the type of juror attorneys want.

“For instance, if there’s a roommate fight or a bar fight, college students are more inclined to get it. If the case is something more legally sophisticated or medical, I as an attorney may overlook a student,” said Larsen, a practicing attorney in Massachusetts for 20 years.

She said she doesn’t feel anything more can be done to educate students about their civic duty, but hopes it will spread by word of mouth and from people getting the experience of being a juror. Students and friends often ask her about the process, and she encourages them to do it.

“Some of their first questions are ‘How do I get out of it?’ and I try to be passionate about telling people ‘Go! It’s your civic duty,’” Larsen said. “If you were accused of a crime, wouldn’t you want someone on a jury who’s like you?”