Who is the Boston Public School system leaving behind?

February 5, 2020

Boston routinely appears on top 10 lists of the most educated cities in the United States, but the city’s high-school and college graduation rates disguise serious disparities in the city’s public school system.

In the 2017-2018 school year, Boston Public Schools’ high-school graduation rate rose to 75 percent, an all-time high. However, while 93 percent of Asian students, 81 percent of white students and 77 percent of Black students graduated on time, only 68 percent of Latinx students did the same.

Many teachers surveyed by Educators for Excellence, an organization that amplifies teachers’ voices in debates around educational policy, think the suspension rate for certain minority populations is a factor behind this disparity. Latinx students make up 42 percent of students in Boston Public Schools, or BPS, but also 43 percent of students who receive disciplinary infractions.

Similarly, Black students make up 31 percent of BPS students, and 46 percent of students who receive disciplinary infractions. White students make up 14 percent of BPS students, but 5 percent of students who receive disciplinary infractions.

“In BPS, they have a fairly low suspension rate, but who they choose to suspend is very alarming.” said Jake Resetarits, managing director of external affairs at Educators for Excellence. “One suspension doubles the chance that they’ll be arrested, and it also makes them 16 times more likely to drop out before graduation, so that’s absolutely not something we want.”

Educators for Excellence’s response to this problem is to call for restorative justice — which they describe as strengthening school-community ties and creating a more positive school culture in order to reduce the opportunity gaps that exist for students of color and low-income students. According to their policy associate, Anthony Morse, similar approaches have succeeded in other cities, including Pittsburgh, whose school demographics are very similar to Boston’s.

There are also large gaps in the proficiency rates among different racial groups. According to the 2019 scores for the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System, or MCAS, more than 20 percent of both Black and Latinx sophomores in BPS scored as “not meeting expectations” in math, compared to 7 percent of white and 2 percent of Asian sophomores.

Lisa Gonsalves, director of Teach Next Year and member of the BPS Opportunity and Achievement Gaps, or OAG, Task Force, thinks that some of this discrepancy may come down to the lack of STEM educators of color in BPS.

“The biggest way to get kids into the sciences is when they can connect with the people who are teaching them. When kids of color see teachers who look like them, who talk like them teaching science, it gives them faith that they can do it too… It’s really important to have teachers of color so teachers can reflect who the kids are,” Gonsalves said. “There is research out there that shows that when kids of color have a teacher who is like them, it can get them really excited about STEM or math or science, and they are more likely to pursue that.”

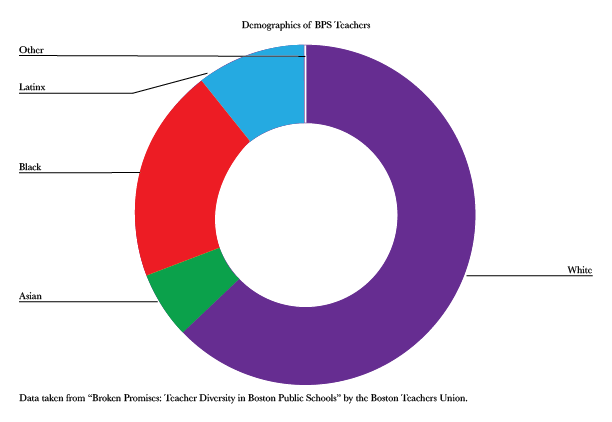

According to Boston Teachers Union’s 2018 paper, “Broken Promises: Teacher Diversity in Boston Public Schools,” approximately 38 percent of BPS teachers are people of color, compared to 86 percent of the district’s students.

The system is still under a court order from the 1970s requiring that at least 25 percent of its teachers are Black, yet the district’s percentage of Black teachers has gone down — actually falling still below 25 percent — and the number of Asian and Latinx teachers remains disproportionate to the number of Asian and Latinx students in the system. To alleviate this discrepancy, the OAG task force recommended that BPS increase its teacher diversity and cultural proficiency.

Gonsalves explained the importance of having diverse and culturally proficient educators using an example she saw in a Boston classroom. According to her, it is fairly common for Black working-class parents to phrase their commands as mandatory phrases, while white middle-class parents often phrase commands as questions. A cultural difference like that can cause issues in the classroom.

“[The white middle-class teacher] says ‘It’s time to read. Do you want to read?’ and all of the little middle-class white kids come running because they know what it means, and the Black kids don’t. One little boy was in the back playing, and he didn’t come running and the teacher says, ‘Lynn do you want to read now?’ Lynn says no because it was a question and growing up, when a parent asked him a question it was a real question,” Gonsalves said. “So Lynn ends up getting in trouble for being defiant and not following the rules when all he did was do what he does at home. If the teachers knew that, can you imagine how that changes the classroom?”

Among the largest disparities in BPS, the difference between English Language Learners, or ELLs, and their primarily English speaking peers comes high on the list. In 2018, only 63 percent of ELLs graduated on time. The next year, 53 percent of ELLs from BPS entered college, compared to 66 percent of students overall.

“We found that families were not getting the right information to make confident choices about the best options for their children,” said Angelina Camacho, a current BPS parent and a member of the system’s ELL Task Force. “Also, there is an ongoing issue with the language around encouraging them to properly identify themselves as ELL and the value of doing so. A lot of families still feel like they would be at a disadvantage if they were allowed to be tagged as ELL.”

Camacho has experienced the district’s flaws in regard to ELLs and their families first-hand while attempting to support her own son’s bilingualism and biculturalism.

“As an acculturated Latino who has a bilingual son, it’s been hard for the system to properly interpret how my son should engage in the school, which has required a lot of support,” Camacho said. “I’ve had to hire outside of BPS, which was quite a financial challenge, but one that I was thankfully able to manage — I say manage lightly — during the most critical years of his academic learning. Now that he’s a little bit older, it’s a little easier to work with him one-on-one.”

In a system where 71 percent of students are economically disadvantaged, not all families are able to access outside resources to support their children’s language learning. However, hiring bilingual teachers is more difficult than hiring monolingual teachers. According to Gonsalves, many bilingual teachers have issues passing the Massachusetts Tests for Educator Licensure, or the MTEL. The system often waives the MTEL for these teachers and helps them to pass it, but this still presents hoops for everyone to jump through.

Most BPS stakeholders agree that the system needs to take steps to improve its achievement gaps. Among them is Superintendent Brenda Casellius, who, in the fall of 2019, went on a community engagement tour that culminated in a strategic vision for the next five years that includes working to close student achievement gaps.

“You can see it outlined in that Boston Globe article about valedictorians, that even people that graduate top of their class are not being given the skills to then participate in the economy or participate in college,” Morse said. “It’s an issue that students don’t think they have the skills to go out into the world and be at the level that [they] need to be.”