Professor Mona Minkara’s interactive classroom requires no sight

Minkara was diagnosed with macular degeneration and cone-rod dystrophy at age 7.

February 11, 2020

Professor Mona Minkara currently provides the Northeastern community and the scientific community with living proof that vision does not necessarily require sight.

Minkara is an affiliate faculty member at the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology at Northeastern University and is currently teaching her first semester of Biomolecular Dynamics. The factor setting her apart from many of her colleagues, however, is that she does it all without the ability to see.

At the age of 7, Minkara and her younger sister, Sara, were diagnosed with macular degeneration and cone-rod dystrophy.

“What that really means is that my retinas are falling apart,” she said. “I was conscious of being diagnosed. Everybody told me I was going to be totally blind when I was 7. I didn’t really understand it. I don’t think I really believed it.”

As she transitioned to a life of visual impairment, Minkara encountered hardships in her early schooling.

“I remember pushing really hard when I was in seventh grade to read an exam that I had, and actually blacking out from forcing my eyes [and] pushing so hard,” she said. “And I think that made everybody believe I [was] actually losing my eyesight. It made me believe it more.”

Minkara did not begin to learn Braille until a year and a half ago, and instead used audio-technology ranging from computers to a human-helper for quizzes and exams to power her through her education. However, as she progressed through school, it became apparent that the road ahead would not be an easy one.

“I was for the longest time put in lower-level classes because I was blind. And that was kind of a disservice to me,” she said. “I remember having to fight for taking advanced classes.”

Her passion for science grew as she moved into high school, but so did the level of resistance she faced.

“The teacher on the first day of classes was like, ‘You don’t belong in this classroom, I am not going to change the way I teach for you,’” Minkara said. “I got the highest grade in the classroom by the end of the year and she actually apologized to me. But that made me believe that I could do more, too.”

High school gave Minkara the momentum to realize that she was not solely defined by her blindness, and she could in fact be as successful as, if not more than, her peers. She enrolled at Wellesley College as a double major in Middle Eastern studies and chemistry.

“I always talk about the story of asking for access assistance and being told that the school didn’t provide tutors, and being like ‘I don’t need a tutor, I need literally somebody to make this stuff accessible to me,’” she said. “So, fighting through that, getting what I need and then thriving. Wellesley was an amazing time.”

While flourishing in her classes, Minkara also received a National Science Foundation Research Experience for Undergraduates Award for each summer that she was enrolled. When she graduated in 2009, she was chosen as the commencement speaker.

After graduating from Wellesley and doing a year of research, Minkara applied and was accepted to a doctorate program at the University of Florida. Her research there “focused on biological systems and computational-chemistry-aided drug design,” according to her website.

“One of the reasons I picked the University of Florida was [because] the disabilities office just laid out the red carpet,” she said. “They’re like, ‘Whatever you need to succeed, we will help you.’”

Minkara completed her doctorate degree and was then given a postdoctoral opportunity by Professor J. Ilja Siepmann at the University of Minnesota.

“He said something that kind of almost shifted my entire view of myself, which was, ‘I see how people do research and I see how you do your work. And you do it differently. You have to think outside the box. I need people who think outside the box to solve problems that nobody else has solved.’ He saw my blindness and the way I think as an asset.”

Professor Siepmann changed the way Minkara viewed herself and her role in the world by showing her that her angle of thinking is an advantage.

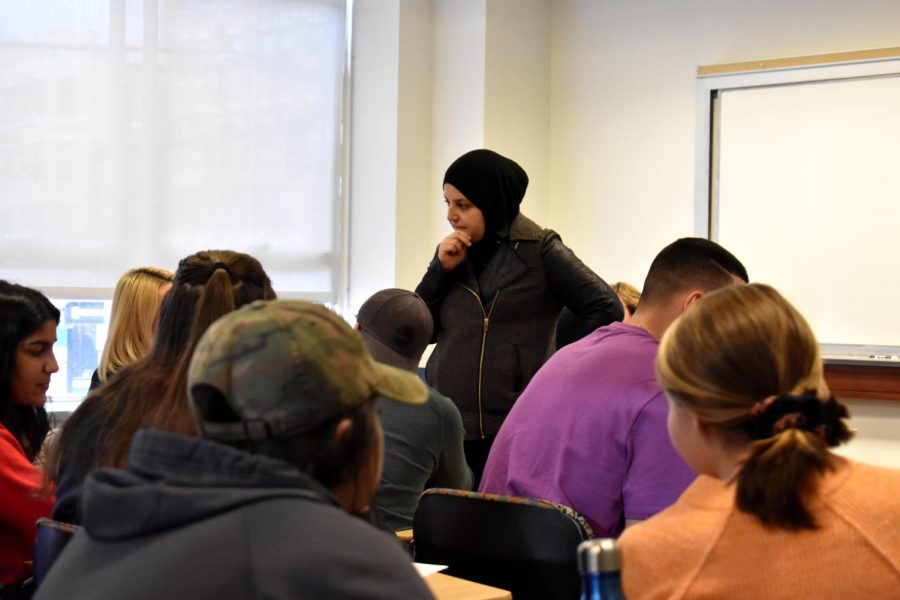

After completing her postdoctoral degree, Minkara knew that she wanted to come teach and do research at a university. She is now leading 36 students in her first semester of teaching at Northeastern University.

Ben Greenvall, one of Minkara’s research access assistants provided through NU, helps out in class to keep things running smoothly.

“It’s incredibly interactive,” he said. “[Minkara] really stresses verbal response and having a presence that is not visual because people looking confused means nothing to her. From the get-go, she stressed that students need to be verbal and engaged.”

While Greenvall is there to help keep the class organized, Minkara stresses that he is there to help her and her only — he is not a teaching assistant.

“The students understand that he is there to help me do my piece,” she said. “You have a question, you ask me.”

Many of Minkara’s students agree that her class is more engaging than others they have encountered before.

“The class environment, since she is a blind professor, it’s a very interactive environment where you kind of have to speak up,” said Rohan Shukla, a third-year bioengineering major. “She can’t see if you are raising your hand. I feel like it’s a good atmosphere where everyone is just participating.”

Leonardo Simonelli, a third-year bioengineering major, said the class environment can present a challenge to students trying to participate. “You definitely need to go a little bit out of your comfort zone, because often if you want to get noticed it is enough to raise your hand.”

Minkara believes that her work in the classroom not only provides students with the knowledge they need to succeed in chemistry, but also with the knowledge of accessibility they need to pass along to others and inspire change.

“They’re raising their own awareness about how to be accessible and communicate and be inclusive,” she said. ”They should be aware of accessibility. And I think it is happening. That propagates a social change. Then they will go on, and whatever they end up doing, they will keep [accessibility] in mind, and it will normalize having a blind science professor.”

According to Minkara, audio plays a huge role in keeping her organized. She uses voiceover technology to make use of her phone, watch and computer. Play-Doh and molecular modeling kits help her visualize her research, and she even has a Brailler device that translates words to Braille.

In addition, she has assistants, like Greenvall, provided by the university to help her with her research and in class. She communicates with them via walkie-talkie when she needs something.

Beyond teaching, Minkara loves to travel and has used her position as a blind scientist to spread her message around the world.

Her sister Sara runs a nonprofit called Empowerment Through Integration, which focuses on empowering people with disabilities and transforming society to be more accepting of those individuals. For the past two summers, Minkara has gone to Lebanon with her sister’s nonprofit to help teach a STEM curriculum that is fully accessible to the blind at a summer camp.

Minkara was also the 2019 winner of the $25,000 Holman Prize, which she is using to film a documentary series called “Planes, Trains, and Canes,” in which she travels to six cities around the world independently using only public transportation.

“I went to Johannesburg, London, Istanbul, Singapore and Tokyo. I really had a different experience in every city that I went to,” Minkara said. From petting lion cubs in Johannesburg to exploring apothecaries in London to getting lost in Istanbul, the trip was, in her words, “insane.”

Minkara’s travels abroad have inspired her to continue to spread awareness about accessibility for the blind and disabled. She emphasized Tokyo as a place that was very accessible. “After Tokyo, we are years behind … and that needs to change.”

Despite the difficult road Minkara had to endure to get to where she is, she urges others in similar situations to remain strong.

“Don’t see it as suffering. Don’t despair — people around you might — but you shouldn’t. And follow your passions.”