Panel elaborates on abolition and discusses abolitionist practice in contemporary art

The Tufts Art Galleries held a panel on abolitionist expression in contemporary art.

October 6, 2020

Black artists and academics clarified abolition and showed how art is used as a form of activism and community empowerment in an online program of the Tufts University Art Galleries on Sept. 17.

Moderator Abigail Satinsky of Tufts University Art Galleries’ panel “What is an Abolitionist Practice?” began the session by reading statements from Tufts University acknowledging Black history and announcing its stance for Black lives and against imprisonment and police brutality.

“As galleries situated in an educational institution, we have enormous responsibility to know upon [whose] land we live and learn and to proactively share that history,” she said. “This acknowledgment is a work-in-progress and the beginning of that process.”

In addition, Satisnsky quoted the definition of abolition by Critical Resistance, an activist group against the prison-industrial complex, and referenced Angela Davis’ “Are Prisons Abolished?” to explain the prison abolition movement.

Mainly consisting of Black artists and academics of diverse disciplines, the panelists emphasized abolitionist practices are meant to spark creation, as opposed to destruction as vilified by mainstream media.

Dr. Kerri Greenidge, an assistant professor at the Department of Studies in Race, Colonialism and Diaspora at Tufts University, gave a much-needed history of Bostonian Black radicals. Greenidge’s paraphrase of former Celtics player Bill Russell and John F. Kennedy’s remarks on Boston reflect its current disparities: Russell named Boston the “flea market of racism,” whereas JFK, who was schooled in the predominantly white and wealthy town of Brookline, thought Boston was racially liberal.

Providing additional historical context for 21st-century abolition, Greenidge paraphrased a timeless but rarely-mentioned quote of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The apathy and complacency of white, moderate liberals are as detrimental to, if not worse than, outright hatred, such as confederate flags. Understanding that the Democratic presidential candidate, Joe Biden, can be seen as the embodiment of white liberal complacency, Greenidge still reminded everyone that “this is the year to vote.” Because otherwise, “these conversations will be for naught.”

Greenidge highlighted the Black Radical movements in the 19th century for the lack of freedom of those enslaved and that the Boston police colluded with southern plantation owners to capture fugitive slaves. She emphasized that just as Black literature is indispensable, the complete history of past atrocities and Black peoples’ fight for freedom is necessary as well.

“Only by remembering completely can we enact revolutionary change,” Greenidge said.

Her colleague, Dr. Kris Manjapra, elaborated on the “warm” definition of freedom, whose focus is on restoration and whose energy is cornucopian, as opposed to the “cold” one that is only formal, but lacks meaning.

Manjapra referenced W.E.B. DuBois in furthering the discussion of abolition as a positive act that is not only terminal (when bondages are supposedly freed), but also a generative one. The act of creation, like restoration, is “how Black and Indigenous communities reconstruct their realities while living in regimes of white supremacy and racial terror,” such as the present one that Greenidge describes as “fascist.”

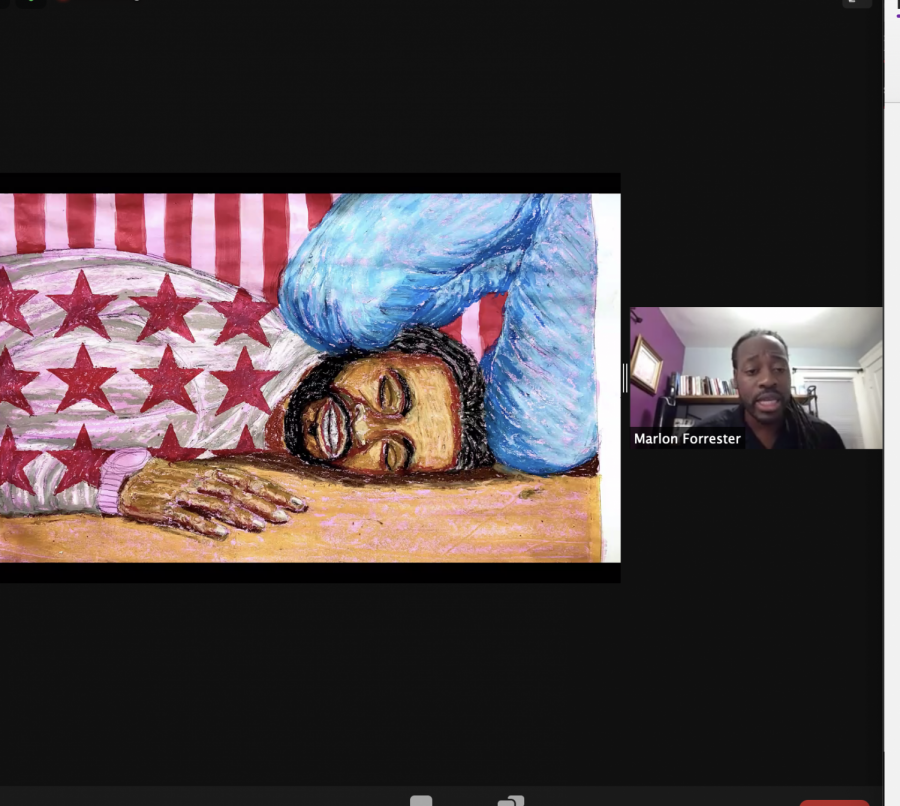

In this vein, art is vital. Two artist-panelists exemplify Manjapra’s clarification of abolition: Marlon Forrester, a member of the African-American Masters Artists in Residence Program at Northeastern University, and Kai Grant, the owner and chief curator of Black Market Nubian, the public art initiative in Nubian Square (formerly Dudley Square). Grant’s work on murals around Roxbury is both “non-gentrified” and a “disruptive statement,” as well as a form of artistic and economic activism focusing on creative freedom and redistribution of wealth.

On the topic of public art, Anni Pullagra, another panelist and curator at the Institute of Contemporary Art, believes that “museums are businesses when they should be public spaces.” And because capitalism is a “cultural system,” and museums are not exempt from it. She then added, “You can’t Cliff-Notes your way through abolition. You just have to do it.”

Forrester especially foregrounded restoring the selves and consciousness of Black people, since they live in a world where their identities are juxtaposed against others’ views of them. As he introduced his work, Forrestor mentioned that he and other resident artists were locked out of their studio space by Northeastern’s unannounced lock-change in June.

Showing a photo of Bob Marley’s dreadlocks, Forrester explained that their origin was the belief that to cut or defame anything on the body would be sacrilegious. Furthermore, he said that this concept is related to the dichotomy between Zion, a utopian space existing for Black people, and Babylon, the “carnal” and current state, “where Black people could be attacked, killed, and brutalized.”

Forrester used this example to show that abolition is the opposite of its portrayal by mainstream media. Instead of destruction and chaos, abolitionist practices are centered around restoration and community to grant the long-overdue peace and justice for Black people.

Critiques of civil rights protests and their civil unrests have always persisted. In yet another wave of fight for the human rights of Black people, this panel better explains the side that the mainstream media and the quasi-elitism of academia have obscured from the general public — the meaning and history of abolition for Black people. And, it serves as a resource for Black people to create their safe space through art.

“Black consciousness is not about anti-white,” Forrester said, “but about Black hope.”