Women’s hockey sees fewer spectators and opportunities than men’s

May 15, 2022

Tensions rose on the ice as the Northeastern University women’s ice hockey team (31-5-2, 21-3-2 HE) skated out of the locker rooms for its 14th-straight Hockey East tournament appearance Feb. 26.

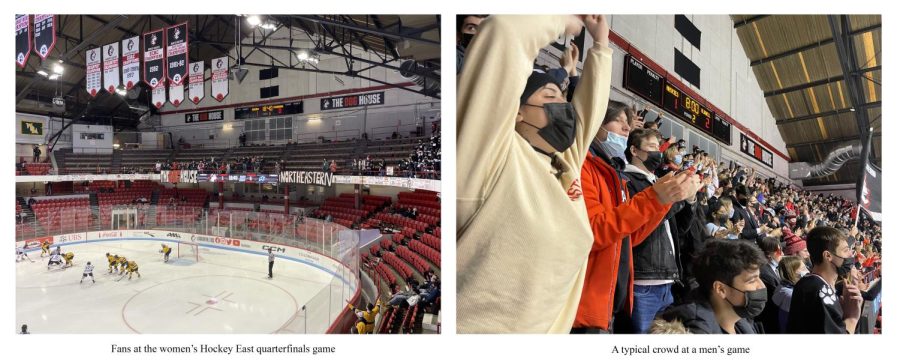

The team was set to face Merrimack College (8-25-1, 6-20-1 HE), a group that barely made it into the playoffs. Northeastern’s Huskies had already beaten the Warriors three times earlier in the season with scores of 8-0, 3-1 and 5-0. The game should have been huge, and it was; it ended in another 8-0 clobbering of Merrimack, but only 384 fans saw it happen.

The game was powered by senior forwards Alina Muller and Maureen Murphy. Murphy earned her fourth hat trick of the season, while Mueller, upon her return from her third Winter Olympics, promptly tallied three assists and broke the school record for career assists during the game.

Graduate student goaltender Aerin Frankel also made history that night, earning her NCAA-leading 11th shutout of the season and her 100th career win — becoming just the sixth woman in NCAA history to do so.

Women’s sports have historically been overlooked in favor of their male counterparts. They are under-funded, under-viewed, and just plain ignored. In 2019, the average NBA salary was $6.4 million, while WNBA players only made $71,635 on average. Additionally, according to an equity pay lawsuit filed by the United States’ women’s soccer team March 2019, although the women’s national soccer team played more games and brought in more revenue than the men’s team in 2017, the men were paid more. This year, each team in the Canadian Women’s Hockey League will see an average salary of between $30,000 – $37,500 Canadian dollars — equivalent to $23,360.85 – $29,201.06 U.S. dollars. In the National Hockey League, however, the average salary is $2.96 million per year.

Northeastern’s athletics programs are no exception.

Boston is a hockey city. It is home to the Boston Bruins — the third-oldest active NHL team and the oldest one that is based in the United States. The Bruins have won six Stanley Cup championships, tied for fourth-most of any team in the NHL and second-most for teams located in the United States. Hockey culture in Boston is strong.

That culture translates to the colleges located in Boston. Every weekend, thousands of students and community members flock to Northeastern’s Matthews Arena — the world’s oldest multi-purpose athletic building and home to the world’s oldest artificial ice sheet — to watch the men’s hockey team play.

But Northeastern has two hockey teams — a men’s and a women’s. The women’s team sees only a few hundred fans in the stands every weekend.

The men’s conference and national rankings were all over the map this season, yet the team drew an average of 3,646 fans per game. The women, however, held the top spot in the team’s division, Hockey East, for months and were consistently ranked in the top-five teams nationally. On March 5, the women’s team headed to the Hockey East Championship, fighting for a fifth-straight title in front of over 6,000 empty red seats at Matthews..

Northeastern’s women’s hockey team ended the season with a 31-5-2 record and third place national ranking, winning Hockey East for the fifth straight year and playing in the NCAA Frozen Four for the second year in a row. Twelve of those wins were blowouts. The players fought hard from beginning to end this season, and many have been recognized with several top awards along the way.

Kendall Coyne, a forward on the team from 2011-2016, was recognized as the best player in Division I women’s hockey when she was given the Patty Kazmaier Award in her senior season after being a top-10 finalist for three years. In her time at Northeastern, she was nationally recognized over 30 times. Coyne is also a three-time Olympian, taking the United States to the gold medal game each year.

Coyne is just one of the program’s 11 Olympians. This year, Mueller played for Team Switzerland for the third time. In the 2014 Olympics, she became the youngest ice hockey player ever to win an Olympic medal, scoring the game-winning goal in Switzerland’s bronze medal game. She was 15 years old. Mueller is also a four-time Kazmaier top-10 finalist.

Frankel, on top of the accolades mentioned above, was awarded the Kazmaier prize last season. In 2021, she was given the Women’s Hockey Commissioners Association’s inaugural Goalie of the Year award. Frankel also won the 2022 WHCA Goalie of the Year Award, four consecutive Hockey East Goalie of the Year awards and the 2021 U.S. College Hockey Organization Player of the Year award.

Graduate student defenseman Skylar Fontaine is another of the team’s highly-decorated members, earning Hockey East’s Best Defenseman award for three consecutive seasons. This year, she became the first-ever defenseman to lead the NCAA in assists, averaging 1.08 assists per game this season. On May 13, she graduated as the program’s most awarded blue-liner.

Suffice it to say, the program is full of strong, talented athletes.

Why is it that such a successful and energetic team has trouble drawing attention? Suzanne Knoll, mother of junior forward Katy Knoll, has some ideas.

“It’s unfortunate that [the school doesn’t] figure out a way to draw more of the student body in and do either giveaways or food, something to bring in people,” Knoll said.

Owen Welch, a third-year physics major who runs the DogHouse, the school’s fan base, said they have been trying to do just that.

Over the last few months of the season, the DogHouse taped gameday flyers on doors, walls and posts around campus to advertise the upcoming women’s games and posted game reminders, player celebrations and victory memes on its social media accounts. It even gave away branded DogHouse fanny packs at a women’s game in January, and still, students don’t show the same level of support for their female Huskies that they do for their male Huskies.

This is, in part, due to poor scheduling of women’s games. When both teams play home games on the same day, the women are shoved to the back burner. The women play most of the teams’ home games Friday afternoons so the men can use the arena in the evening — during primetime.

While there were only 1,343 spectators at the women’s Hockey East Championship this year, the men’s Hockey East Championship game saw 12,049 fans in the stands, even though both games happened on two separate Saturdays in March at 7 p.m. Many men’s games are schedules at more accessible time slots, so more fans are able to attend men’s games.

First-year Audrey Romanik, a dedicated member of the DogHouse, told the News she had to run from class or work to attend women’s games this year, and even then, she often arrived late.

Women’s sports are stuck in an unending cycle — attendance numbers cannot grow without better game times, but if there is no audience to justify giving primetime slots to women’s hockey, women’s teams will be stuck playing in the afternoon.

Sophomore defenseman Abbey Marohn expressed her concerns with societal ignorance and lack of exposure to women’s sports across the board.

“The men’s hockey games are a big, Friday-night deal,” Marohn said. “I think if a lot of people came and were able to watch [our games], maybe they would be more interested in [women’s hockey].”

Romanik agreed with Marohn. She said she believes the problem lies mostly in the lack of energy and support for the women’s team.

“Because people have experienced men’s games more, they’re more excited about them,” Romanik said. “They know the crowd is going to be there. They’re like, ‘Oh, it’s going to be a fun game.’ Every time you come to a women’s game, it’s a smaller crowd.”

Students who spoke with The News said they enjoy the palpable, wild atmosphere of the crowds at men’s games. Women’s games are quiet because the audience numbers aren’t high enough to be rowdy — the women’s team’s audience average this season was only 524.

While Hockey East is partially to blame for inaccessible game times, this problem is not exclusively a conference issue. The men and the women both participate in a Boston-wide Division I hockey tournament called Beanpot, but while the men get to play in TD Garden — the arena in which the Bruins and Celtics play — the women are stuck at campus sites.

For Husky mother Deborah Tancrell, this is concerning. Tancrell has two children in Northeastern’s hockey program — the aforementioned defenseman Fontaine and her brother, men’s sophomore forward Gunnarwolfe Fontaine. Both are talented players and team leaders. She said witnessing the discrepancies her children face bothers her.

“Most disheartening was when I went to the Beanpot at the TD Garden and saw a sold-out crowd watching and cheering on Northeastern, and you come [to Matthews] and it’s parents and friends,” Tancrell said.

Marohn, however, has a positive outlook regarding Beanpot.

“The Beanpot game that we had recently, we had a lot of people come to the DogHouse, and that was really cool because I think a lot of people probably got exposed to women’s hockey for the first time. And that’s one thing that’s really big about it, too — the exposure,” Marohn said.

This year, 1,755 fans watched the women’s Beanpot semifinals — the biggest turnout of the season.

Despite its exceptional, record-breaking performances throughout the season, the women’s ice hockey team continues to be overlooked by the community and school it represents. The solution is increased exposure and accessibility.

Inaccessibility starts early. According to Marohn, hockey leagues for young girls are few and far between.

“I grew up playing boys’ hockey,” Marohn recalled. “Girls’ hockey’s not as big. It’s much bigger now for younger teams, but I didn’t start playing girls hockey until I was 14, and a lot of the girls here did the same.”

The disparities don’t end in youth sports. For example, in professional leagues many female athletes have to find alternative day jobs; Paige Capistran, another highly-decorated Northeastern hockey alumna, simultaneously plays for the Boston Pride, Boston’s NWHL team, and serves as an assistant content reporter for NESN. Last year, the NWHL doubled their team salary cap to $300,000. For Capistran and her 20 Pride teammates, that means a maximum annual salary of $14,285 per player. While reporting is a means of survival for professional female athletes, it becomes an option for male athletes post-retirement.

This year, for the first time, the NCAA afforded its Division I women’s basketball teams with March Madness branding and accommodations that matched those of their male counterparts. As a result, a record 216,890 spectators attended the first and second rounds of the tournament.

As is true at the youth, collegiate and professional levels, a fan base for women’s sports does exist; however, the opportunities, accommodations and circumstances that facilitate success are not afforded to female athletes in the same way they are to men.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this story inaccurately reported who schedules men’s and women’s hockey games. The story was updated Monday May 16 at 11 a.m.