Northeastern alumni reflect on abortion rights, reporting 50 years later

October 28, 2022

Fifty years ago, Northeastern was a very different place. Women weren’t allowed to wear pants, the school was majority commuter students and it was one of the more politically conservative schools in Boston, to name a few glaring differences.

About 50 years ago is also when the women’s reproductive health and women’s liberation movements started to come to a head. The birth control pill was made more widely available in 1965, and just eight years later, landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Roe v. Wade protected the right to an abortion.

That right was overturned last summer when the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, shaking advocates, enabling trigger bans and sparking protests across the country. Though the right to an abortion is protected in Massachusetts, Northeastern students are still feeling the effects of the decision.

In a lot of ways, though so much has changed at Northeastern and in the world as a whole, a lot is still the same. Abortion rights are back at the forefront of the country’s consciousness, politics are still divisive and people are still taking to the streets to organize around causes they believe in.

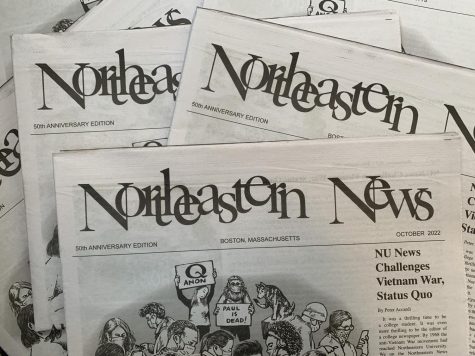

The News has teamed up with a group of editors who led the Northeastern News, the Huntington News’ old name, from 1967 to 1973 to explore the climate surrounding birth control and abortion 50 years ago and where student media fits into the picture.

What did Northeastern students think about birth control and abortion 50 years ago?

Birth control first came on the scene in 1960, when it was approved by the Food and Drug Administration. It wasn’t until 1965 that a Supreme Court case made the distribution of birth control and birth control information legal in all 50 states.

For some, like Margie Peters who graduated in 1970, their friend groups talked about the pill because it offered them a sense of control they had been lacking. Peters was headed into her first year at Northeastern when the distribution of birth control was made legal across the country.

“When I heard about birth control I was thrilled because I was still in school and I was not going to get pregnant because I still had a year and a half or more of school. Birth control was a great thing. It was liberating,” Peters said. “It removed a threat to my plan. And I had a plan — I wanted to finish college and I did not want that to be an issue.”

While the pill was legal, that didn’t mean it was always accessible to Northeastern students in the late 1960s.

“To get on the pill was not always easy,” said Nedda Barth, who graduated with a degree in English in 1970. “At times, the physicians were very demeaning in their approach to you. Many required that you came with your boyfriend, fiance, husband to get on the pill. Some refused to give it to you. So even though it was legal, it wasn’t as accessible as it is now.”

For those in college right when the pill was approved, the topic was sort of hush-hush in some circles, but as time went on, Barth said it became more acceptable to talk about.

“What I can remember is that it wasn’t as talked about at the beginning of my college experience, but as we matured, and as we started to become more participatory in this process there was more discussion among women, not so much with the males on campus, but mostly discussions of which physicians would be more amenable to prescribe the pill,” Barth said.

Donna Doherty, an English major who graduated in 1971 and the first female sports editor for The News, said she recalled finding a source for birth control from another woman on The News. At the time, the staff was divided into two divisions, to account for the co-op cycle. The woman was in the other division, she said.

“To tell you the truth, my friends and I really didn’t talk about it. I got birth control from, actually it was a woman who was a Division A co-op student who worked for the same paper and … she was the person who told me about this doctor in New Haven that you could go to for birth control,” Doherty said. “It was always that it would be a friend, probably no adults unless you had a really cool hip doctor.”

One of the biggest birth control stories The News staff covered in the late ‘60s was reproductive rights activist Bill Baird coming to speak to first-years. Baird spoke to a packed hall of first-year students Sept. 9, 1969, according to a Northeastern News article. He was arrested and jailed after he handed a Boston University college student a condom and a package of over-the-counter contraceptive foam in 1967. Three years after he spoke at Northeastern, the appeal of his conviction culminated in the 1972 U.S. Supreme Court decision that established the right of unmarried people to possess contraception.

For Maxine MacPherson, a 1974 graduate with a political science degree, Baird’s appearance at Northeastern was the first time she had witnessed a discussion of birth control.

“We were in the auditorium and it was packed with freshmen and he did not speak about abortion, but he did speak about availability of birth control,” MacPherson said. “At that time, it was pretty much the pill and that was it. He was not allowed, as I remember it, to tell us where to get it. … And we were not allowed to get it on campus. They could tell you that birth control was available at the health center, but they couldn’t tell you where or dispense it.”

MacPherson, who held a number of positions on The News over her years there including news editor, managing editor and editor-in-chief, was a representative on the student council her first year. The university was against Baird coming to speak, MacPherson said, and the administration made a rule banning abortion ads in the Northeastern News.

“The head of the student council thought we should address that. Eventually what the student council did is they put out a book about birth control,” MacPherson said. “The faculty, of course, were not happy with it because it was really against the rules.”

While birth control was becoming socially acceptable and available, many still considered abortion taboo. Of course, there were a handful of years where the birth control pill was legal while abortion still wasn’t, but that didn’t mean abortions didn’t happen.

Barth said she recalled a woman she met while volunteering who had come to the United States to go to school. The woman got pregnant and attempted a coat-hanger abortion, a dangerous method of attempting to terminate a pregnancy. The woman’s roommate called Barth hysterically as the woman hemorrhaged in their dorm. The woman was taken to the hospital and survived a hysterectomy, Barth said, but she never saw her again.

“This was not uncommon. I had friends who went to Canada for abortions. Somebody went to Sweden,” Barth said. “This is just speaking from my own experience, nobody I know decided to have a child. Nobody wanted to continue at college and have a child.”

Mary Gelinas, an English literature major who graduated in 1971, remembers wandering Kenmore Square while she was in college, afraid she was pregnant, and said the experience was very isolating and terrifying.

“I was by myself. I don’t remember talking to anyone about it,” Gelinas said. “I was just on my own kind of, ‘what am I going to do?’ I don’t even remember talking to Nedda [Barth] about it, and she would have been the person I would have spoken with.”

Roe’s overturning earlier this year was virtually impossible to miss, making headlines for days and spurring national protests. The same wasn’t true of the original case’s decision, MacPherson said.

“I had my own experience with abortion and that’s why I remember, but I don’t remember it being discussed quite as much in the early times,” MacPherson said. “When Roe v. Wade, when the Supreme Court made that decision, I remember that there was a women’s group on campus that celebrated that. I shouldn’t say it wasn’t a big deal, but it wasn’t the number one topic.”

While abortion and birth control were big issues in society at the time, they were far from the only ones. The late ‘60s and early ‘70s also saw the Vietnam War, the Black Panther movement and the Civil Rights Movement.

Such turbulent times pushed a change on Northeastern’s campus, alumni told The News.

“Northeastern was at the beginning, when I came in ‘65, pretty conservative,” Barth said. “And then, as the years went by, it became more political and Northeastern became one of the most political campuses in Boston. I mean, we took on the role that really no other college, as far as I know, really undertook. We had rallies and we had speakers and we had so many different opportunities to conduct dialogue that I don’t think many other colleges did. And it was interesting how in five years it totally changed.”

Northeastern was no exception to the radical changes facing the nation. For Gelinas, the turbulence created an exciting and illuminating time to be in college.

“The whole country was just kind of in a turmoil about a lot of social issues. I would say for me at first it was quite shocking, because I came from, in hindsight, a very sheltered environment,” Gelinas said. “There I was, in the midst of all this — it was a period of drugs, sex and rock and roll, so it was both exciting and terrifying on some level. … I would say it opened my eyes in a very important way.”

Woodstock happened the summer before MacPherson started at Northeastern, creating an interesting societal backdrop for her to start college. MacPherson is from a small town in New Jersey and her father was a government employee.

“He said to me as he dropped me off at … Speare Hall … ‘please don’t demonstrate against the government,’” MacPherson said. “And I said, ‘Well, I have no intention of doing that.’ My first demonstration was Oct. 15. I think I got to campus around the 17th of September.”

The area surrounding campus was ripe with protests, many of which reporters for The News covered.

“I would think that it was one of the most turbulent times on campuses ever,” MacPherson said. “But at the same time, the best time to be there.”

For many of the previous editors who spoke with The News, their Northeastern experience was an eye-opening one, forcing them to interact with people from different backgrounds and to confront the topics of the day.

“I credit my time at Northeastern, and at The News, with me growing up as a woman and a woman with opinions and a woman who cared about politics and this thing called ‘women’s lib,’” Peters said.

What was the Northeastern News’ role 50 years ago?

The Northeastern News, as it was known then, was radically different from today’s Huntington News. It was still school supported, published in print every week and worked out of the student center.

While Northeastern as a whole was largely conservative, the staff of the newspaper was much more liberal, Barth said. They covered issues important to them, and the one-time features editor said the staff felt a sort of calling to do so.

“A lot of people took really bold steps. It was important to have The News go forward,” Barth said. “It was not, it was not easy. It was a difficult time, but we were empowered. We felt we were the vanguard, we were the youth.”

The News had no shortage of topics to cover. From the usual Mayor of Huntington Avenue to stories about riots and protests on Hemenway Street, they ran the gamut.

“It was a very tumultuous time. It was probably the most exciting time, either good or bad, to be on a college campus where you really had the freedom, within parameters of course, to write about what was going on,” Barth said.

In 1970 specifically, Barth remembers classes taking a backseat. Classes were pass/fail because of the widespread war protests and she said many of the newspaper’s staff didn’t go to classes anymore, instead staying and working in The News’ offices on the top floor of the student center.

The paper was usually published weekly, but at times the frequency increased to respond to the important stories of the day.

“We went daily at one point during the moratorium right after Kent State, when all these universities were gonna shut down. … We had a 14- to 16-page paper that went out daily and included photography and everything. I didn’t even go to class,” MacPherson said.

Among all the other issues The News was covering, birth control and abortion made at least an occasional appearance. At one point, at an editorial meeting, the staff decided not to run an ad related to abortion.

“I was not the editor, but I remember it being brought up at an editorial meeting and people decided it wasn’t worth it because it wasn’t an issue on campus,” MacPherson said. “People were too involved in other things. The ad that was finally run was probably one column inch by two column inches. I think it was a little tiny ad.”

As far as she remembers, the ad was for a clinic in Brookline that had opened previously to give out birth control and information. Since the passage of Roe, abortions were legal and the ad had a small mention to abortion, MacPherson said.

After the paper ran it, MacPherson said she remembers getting a call from the president’s office.

“They said that ‘did I know there was a rule against running the ads,’ and I said, ‘I believe the rule had to do with the fact that it was illegal to have an abortion but since Roe v. Wade passed, wasn’t it now legal.’ … And they said, ‘Well, the university is really opposed to this, and has been, we could take your papers back,’” MacPherson said. “We all kind of looked at each other, it was just an idle threat. We had heard the threat before. That was always what the university held over The News.”

Under the jurisdiction of Northeastern, the Northeastern News received funding and office space from the school. The paper also had an adviser, and those who spoke with The News said the adviser stayed out of content issues but was a great advocate for the paper.

Gelinas said that the staff of The News felt the work they were doing was important.

“At that point, because I believed I wanted to be a journalist, it just felt really like an important job,” Gelinas said. “I think there was a sense we are all part of something bigger than ourselves. Which I think it is an important part of what the Northeastern News then did, that we were a part of something bigger that was important.”

Across all the editors who spoke with The News, one thing remained consistent: Northeastern News was the center of their lives and the staff was like a family.

“The News became our lives. The News truly did become the central part of my college experience,” Barth said. “It became a real family. There was not a time that we were not at The News. Weekends we would maybe go someplace to get together to discuss because there was so much to discuss — where to go, what to do with, how to handle, and to whom we should speak. … It really was probably the most pivotal point in my college career.”