Archives project complicates women’s suffrage history

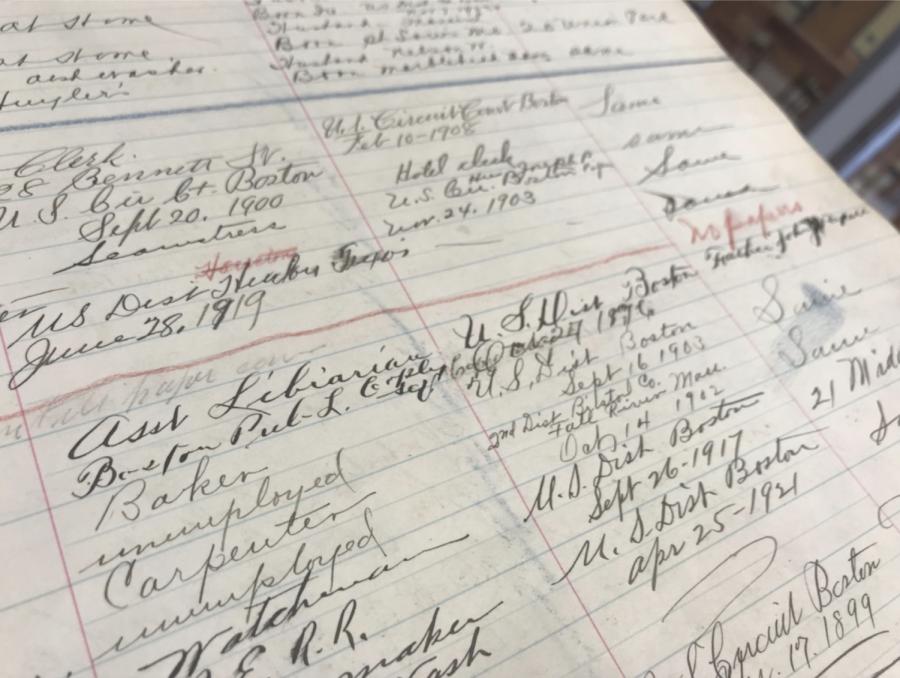

The City of Boston has countless voter registration documents from the 1920s. A team of Simmons graduate students have been working since 2021 to digitalize these archives. Photo courtesy of City of Boston Archives.

December 2, 2022

In 2021, a small team of Simmons University graduate students began work on the Mary Eliza Project, which involves the digitalization of extensive, difficult-to-work Boston voter registration records from the summer and fall of 1920.

The project, a collaborative archive transcription effort between Simmons University and the City of Boston, seeks to make the records more accessible while also developing a more complete narrative of the suffrage movement in Boston.

“Before this project, you’d have to come into the archives to access these records. We have 166 books [filled with hand-written registration information] that are ostensibly organized by ward,” said Marta Crilly, an archivist for reference and outreach with the City of Boston who holds a leadership role in the transcription and research effort.

The city was divided into 26 wards during the election of 1920, Crilly said.

These records represent the first election after the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which gave women the right to vote for the first time in 1920. The research team is looking to both make these records easier to navigate and answer questions about the population that exercised this ability as soon as it was granted. The time-intensive transcription work has not come without its challenges.

“It’s hard to tell too what the women told the clerks and what the clerks recorded. The registration entries are filtered by the people who were writing them down,” said Erin Wiebe, a dual-degree masters student in archives management and history at Simmons University who has worked on this project since its beginning. “I think there’s a lot that gets lost in that transaction.”

This has necessitated additional research into the historical context by the students involved. One highly fundamental area of challenge proved to be the reporting of birthplace within the ledgers.

“The geography in Europe and the Caribbean are recorded differently in the register books. Clerks would record birthplace differently than we would now. The countries they’re recording sometimes no longer exist or are spelled differently,” Wiebe said.

Due to the nature of citizenship and voter laws in the early 20th century, understanding the geography of the time period is crucial to the transcription effort and answering questions about the population of women registering.

“In 1920, women got their citizenship through their husbands. If your husband was naturalized, you would have access to vote. Most of the women who were denied by clerks were reported as having ‘no papers,’” Crilly said.

In addition to presenting their own identifying paperwork at the registration booths, women were expected to have paperwork for their husbands or, in some cases, their fathers, to substantiate their citizenship. Even after the ratification of the 19th Amendment, this fundamental right of American citizens was far from equally accessible to male and female populations, said Laura Prieto, the alumni chair in public humanities and a professor of history and women and gender studies at Simmons. Prieto is another leader of the project and oversees much of the transcription work done by graduate students.

Nationality-based concerns impacted the demographic of this initial wave of female votes, which is of high interest to the research team at the heart of the Mary Eliza Project. They continue to use the archives as a means of better understanding the types of women mobilized by the 19th Amendment.

“Were women of color registering to vote in 1920 in Boston?” Prieto said. “We started with the wards that were most ethnically and racially diverse at the time to try and answer that question.”

This question proved central in the earliest stages of transcription and research.

Wards 6, 8, 13, and, most recently, 1, which cover much of today’s South End, Roxbury, West End, Fenway, Beacon Hill as well as the East Boston neighborhoods, had the most racially diverse residents during the early 1920s. Transcription of the data for women registered in these areas is complete and can be viewed in a spreadsheet format on the project’s website.

The goal of identity-based research questions, like this one focused on racial background, was to complicate the understanding of the female suffrage movement as it is largely taught and understood.

“A lot of the popular narratives of women’s suffrage in America are focused on the political leaders who were chiefly white women and white straight women. This project is a way to reveal the stories of black, immigrant, working-class women who were registering right alongside these more well-known women,” Wiebe said.

The project’s namesake, Mary Eliza Mahoney, encompasses these women who are not often talked about but contributed immensely to this political movement.

“Mary Eliza, we felt, was kind of an emblem for a lot of the research we were trying to do,” Crilly said. “She was a Bostonian. She was born in the West End. She was … one of the first African American nurses … and one of the first American Nurses Association’s Black members. She did a lot of activism … but she was also, in a lot of ways, an average person. … She was a working woman.”

Providing identity to the Boston women in this first wave of female voters, a group little is known about, continues to be of great importance to all of the individuals working on the research team.

“We named our project after Mary Eliza because we wanted to make these questions of race and class central,” Prieto said. “We wanted to make it clear that we were considering all women, who were the grassroots, who were there to claim the right to vote.”

Work on the remaining 23 wards continues and the website is updated regularly with voter data upon the completion of each ward. Ongoing transcription of the Women’s Voter Registers is supported by a grant from the Community Preservation Act and overseen by the Boston City Archives.

Due to the nature of this grant, the publication of data for all 26 wards will be complete by the spring of 2024. Other findings and research developments can be found in blog posts also available on the site, including discussions of “The Queer History of Women’s Suffrage” and occupation-specific groups who were mobilized to vote, including “The Women Artists of Boston’s Ward 8.”

“The blogs that we’ve written are public and written for a general audience, not historians,” Wiebe said. “There are so many different ways that people can use this data set, it’s not just for historians or genealogists. It’s for them but also people who want to know who signed up to vote on their street or in their apartment building in 1920.”

The researchers said they are excited by the multifaceted applications of the project and encourage exploration of the results they have released on the City of Boston website.

“[These archives have] something [of interest] for everyone, it felt like a sort of straightforward transformation into a public spreadsheet that anyone could use,” Prieto said.