Impassioned Destruction, an exhibit at the Old State House, utilizes unconventional art styles and vibrant colors typically not associated with the 18th century to perpetuate the subject of property destruction. “Impassioned Destruction: Politics, Vandalism and the Boston Tea Party” presented by Revolutionary Spaces, dives into the contemporary relevance of disruptive activism through the lens of one of the United States’ most iconic acts of rebellion — The Boston Tea Party.

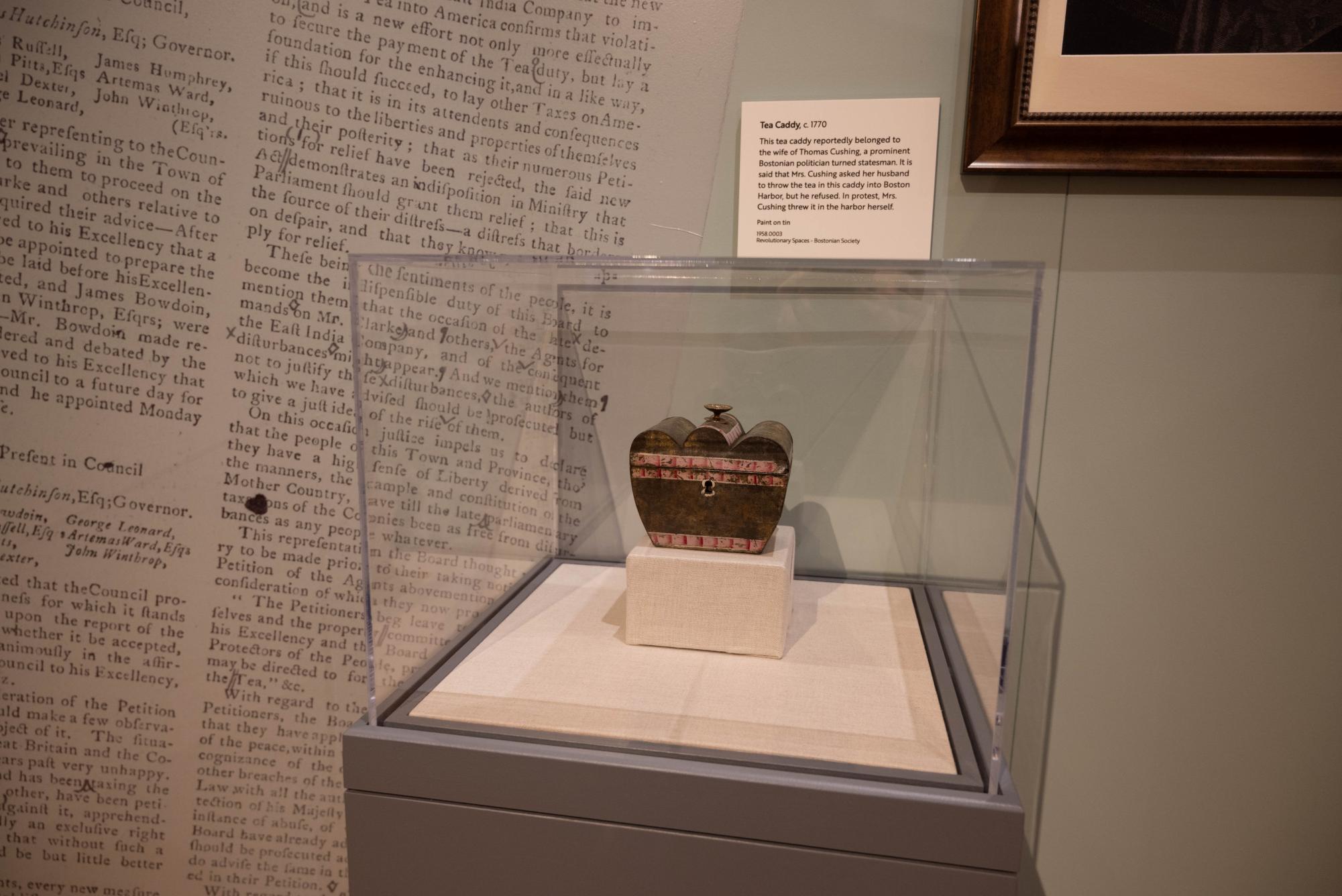

On Dec. 16, 1773, the Sons of Liberty threw 340 crates of tea into the Boston Harbor as a means of protest against the British government’s unfair taxation. The Boston Tea Party took nearly a century to disentangle itself from the ridiculed nature that embodied it at the time. Since then, Americans have utilized vandalism as a form of protest, with the modern day Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection being a notable example. The exhibit encourages visitors to reflect on instances of property destruction in relation to the Tea Party and ponder the justifiability of actions in the pursuit of a cause.

“The bigger goal of ‘Impassioned Destruction’ is to encourage people to think more broadly and critically about their own histories; we can be proud of America and American heritage while still not swallowing the mythology that created our founding,” said Matthew Wilding, director of interpretation and education at Revolutionary Spaces.

The exhibit walks through the cause and effects of the Tea Party.

“The core question I’ve always had about The Boston Tea Party is why do people blanket celebrate it, when, if they are asked, they usually say property damage is bad,” Wilding said.

As visitors progress through the interactive display, they confront the revelation; iconic figures of the American Revolution and United States history held opposing views on this celebrated act of protest.

“The exhibit isn’t always clear. Visitors see the Boston Tea Party and think ‘I know this story;’ however, you continue through and realize George Washington and Benjamin Franklin were against the Tea Party, and it is interesting to think this huge event is celebrated, but these heroes that we have didn’t like it,” said Emily Yurkus, a visitor experience supervisor at Revolutionary Spaces.

Property destruction in the United States, exemplified by events like the Boston Tea Party, remains a tactic for protestors. Upon entrance, the visitors are met with the question: “Do you believe that the participants of the Boston Tea Party were justified in destroying the tea on December 16, 1773?”

On Jan. 14, the vote was yes.

“One of the most interesting parts is to see how the different voting exhibits change. Most days it is some mixture, some days it is all yes and some days — very rare days — they have all been no,” Yurkus said.

The exhibit explains in detail the amount of tea destroyed. With so much destruction, it took over a generation for this act to be turned into an origin story of the country. It was, after all, renamed the “Boston Tea Party” rather than “The Destruction of the Tea.”

In 1773, Parliament passed the Tea Act, a law which granted the British East India Company a monopoly on tea sales in the American colonies. This reaffirmed Parliament’s power to tax the colonies without representation.

The Tea Party marked a notable chapter in Boston’s history, and by comparing events in the other colonies, it becomes clear that Boston’s response was exceptional in terms of its intensity.

“This was an era where property destruction and mob life was part of Boston,” said Malcolm Purinton, an assistant teaching professor of history at Northeastern.

About halfway through the exhibit, another voting station is placed with the question: “Do you believe that participants of the Boston Tea Party were justified in destroying the tea on December 16, 1773?” Despite being the same day and only a few feet from the prior voting station, this one was balanced with an equal number of participants voting yes and no.

In modern day, the Boston Tea Party is recognized as a proud uprising against a tyrannical government. In the exhibit, central figures vocalized it as inappropriate. Only after generations did the event become reimagined.

King George III viewed the destruction as an act of rebellion and in turn passed the Intolerable Acts, or Coercive Acts. This was a series of acts aimed to both assert control over the Massachusetts colony and punish Bostonians. The acts included the Boston Port Act, the Massachusetts Government Act, the Administration of Justice Act and the Quartering Act. Attempting to serve as a warning to other colonies, these acts ultimately became known as the Intolerable Acts due to their perceived infringement on liverities.

“People always talk about the actual events, but you don’t hear about them before or afterwards with the reactions and punishments from the British government,” Yurkus said. “The British government hit the colonists pretty hard with the Intolerable Acts because it literally closed the ports, and Boston is surrounded by water, so it is their way of life. In a way, it dissolves their colonial government; it goes from a little representation to none.”

The exhibit also explores other instances of property destruction in the United States.

“We have a pretty tight criteria for how we select the instances of property destruction, which [is] the main objective needed to be property destruction and not the killing of a person. The people involved need to have expressly said that they supported the property destruction,” Wilding said. “We tried to broaden the political spectrum. As you can see, the events go from a populist conservative movement to a far-left radical movement. Causes from labor movement, religious action and tax policy action were also covered.”

Events mentioned include the Stamp Act Riot of 1765, the Ursuline Convent riots of 1834, the Reading Railroad Strike of 1877 and the Bombing of Gulf Tower of 1974, with the final incident being the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection.

“As staff, before this came out, we knew Jan. 6 would be in here, and a lot of us expected the worst. We are talking about a celebrated moment in American history and then Jan. 6, which people have vastly different interpretations 0f,” Yurkus said.

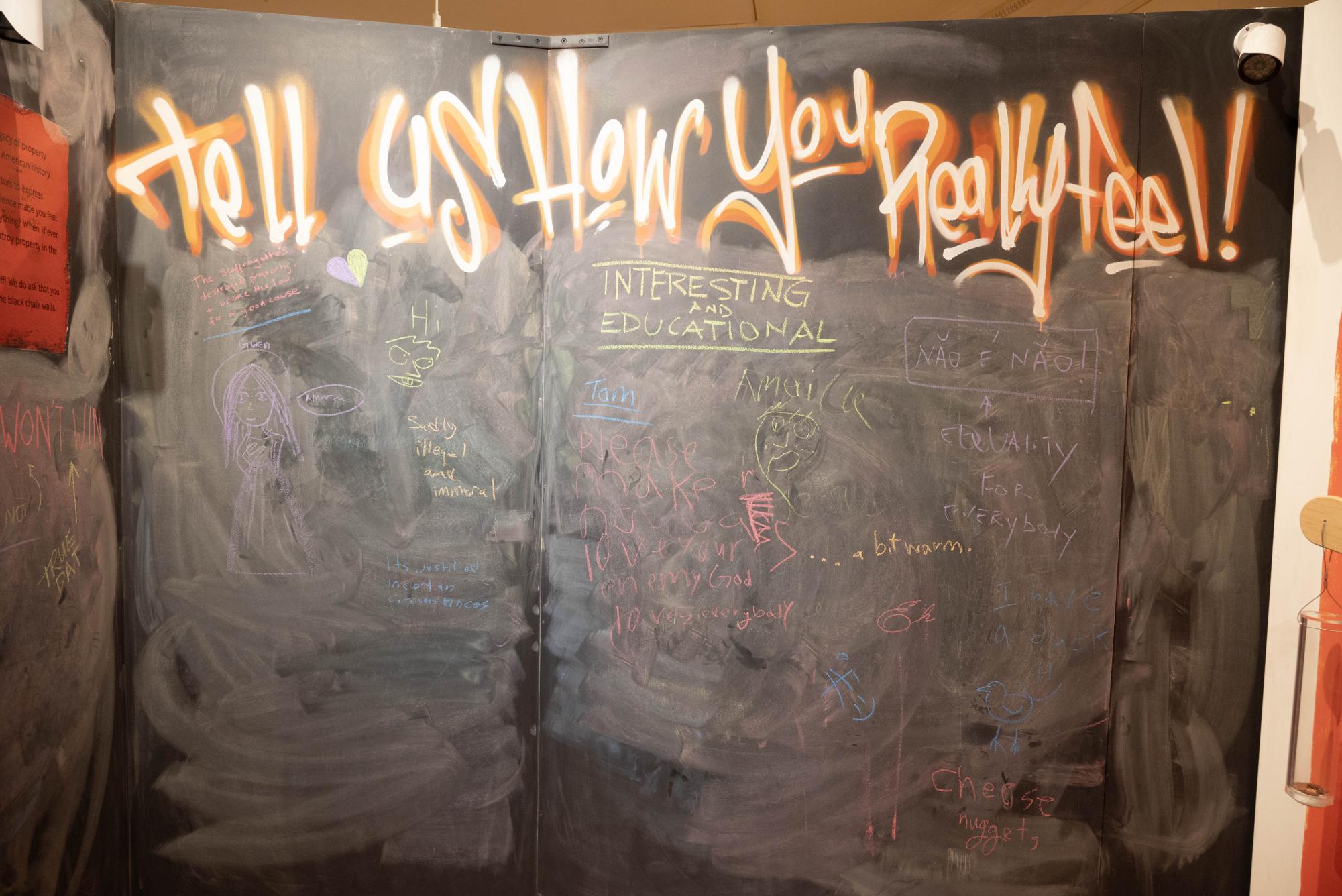

The exhibit ends with a chalkboard for visitors to share their thoughts. Yurkus said visitors use this to express their emotions.

At the end of the exhibit, the question was posed again: “Do you believe that the participants of the Boston Tea Party were justified in destroying the tea on December 16, 1773?”

It was a unanimous yes.