Northeastern’s Planning and Real Estate Committee is developing a “Decarbonization and Resiliency Plan” to mitigate Northeastern’s carbon emissions and it is set to be completed this year. The plan will outline a clear decarbonization timeline to target building emissions and energy inefficiency, marking another step in the university’s efforts to implement climate solutions and initiatives across its network of campuses.

Decarbonization, the process of reducing or eliminating carbon emissions, is essential to combat the climate crisis. Over the next 30 years, Northeastern has committed to working to eliminate carbon emissions from building operations across its 13 global campuses.

The Decarbonization and Resiliency Plan will complement existing sustainability initiatives, including the Climate Justice Action Plan, and will align with plans outlined in the university’s most recent Institutional Master Plan, or IMP.

Currently, the Planning and Real Estate Committee, or PREF, is focused on achieving greenhouse gas reduction goals, improving campus energy efficiency, replacing carbon-intensive energy sources and offsetting any unavoidable emissions from building operations, according to the university’s decarbonization website and IMP. To achieve these targets, Northeastern will reduce the intensity of energy use in its buildings and transition to clean energy sources.

“This plan has been a long time in the making,” said Matthew Eckelman, associate professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

Eckelman is one of several faculty members contributing to the university’s decarbonization efforts. He leads research focused on evaluating building materials’ potential to act as carbon sinks — materials that store carbon rather than release it into the atmosphere.

On the Boston campus, PREF is first tackling the city’s stringent building regulations. One of its newest and strictest regulations, the Building Emissions Reduction and Disclosure Ordinance requires every building in the city to report its energy use and meet climate targets.

This poses a challenge to Northeastern, as its Boston campus is home to several buildings that were constructed more than a century ago. These structures often have poor insulation and outdated HVAC systems and would most likely have to be retrofitted to upgrade their energy performance.

To address this, the university is investing in the renovation and replacement of some of its oldest structures.

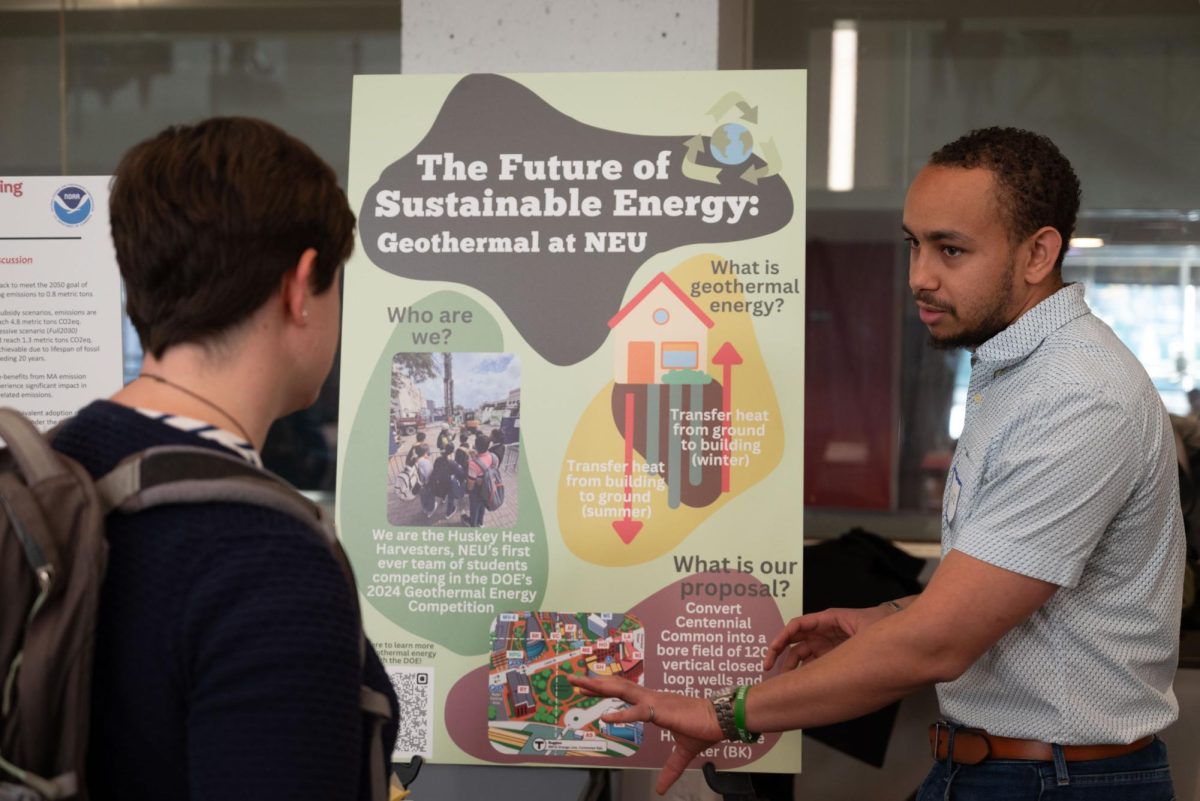

Currently, Northeastern is in the process of undertaking a massive overhaul of the historic Matthews Arena, the 115-year-old multipurpose athletic facility home to the school’s hockey and basketball teams. As part of the reconstruction, several geothermal wells are being drilled into the parking lot, replacing the fossil energy and steam-based heating and cooling.

Other campus buildings, including White Hall, Forsyth Building and Burstein and Rubenstein halls, could also be subject to demolition and reconstruction in the coming years, according to the IMP.

However, the university must be strategic when it comes to constructing new buildings in order to avoid embodied carbon, the greenhouse gas emissions produced during construction. While a building may be more energy efficient in the long run, the construction process is highly energy intensive.

“Initially, as we invest in new renewable energy facilities, there is a certain energy cost to it. That’s why it’s really important to be sure that those facilities will be able then to deliver a lot of energy so this initial cost is compensated,” said Magda Barecka, an assistant professor of chemistry and chemistry engineering who leads the Barecka Lab on campus. Her lab is working to enable a smooth transition toward a carbon-neutral economy.

The university is converting many of its older buildings to no longer run on steam, instead relying on alternative HVAC technologies and “high-pressure” steam, according to Eckelman and the IMP.

Right now, PREF’s decarbonization plans are on track to be completed by fall 2025, as laid out in the IMP.

“It’s very well-developed in terms of options they’ve looked at. They’ve already begun implementing it, but you can’t do everything at once. In many ways, the technologies already exist to do what we want, but it’s a matter of having the time to do them. You can’t decarbonize a building when you’re holding classes in it,” Eckelman said.

As they work toward finalizing this plan, students appear to be generally satisfied with the work completed so far.

“I think it’s important that the administration is passionate about the same things as students. I think a lot of students do care about this issue, but it’s hard to improve [student] involvement,” said Caroline Bayer, a fourth-year environmental studies and history combined major.

Although Bayer is actively involved in environmental organizations on campus, like the Husky Environmental Action Team, or HEAT, she wasn’t familiar with the decarbonization plan until recently.

“Most people don’t even know this plan exists,” said Orla Molloy, a fourth-year environmental studies and political science combined major and the vice president of outreach for HEAT.

Molloy first learned about the university’s decarbonization plans at a Student Sustainability Committee meeting, where she serves as one of two student co-chairs. In the past, students have been directly involved in projects like the Climate Justice Action Plan, which incorporated a student steering committee.

However, the Decarbonization and Resiliency Plan is still in its early stages, so it is possible a formal student committee could be established in the future.

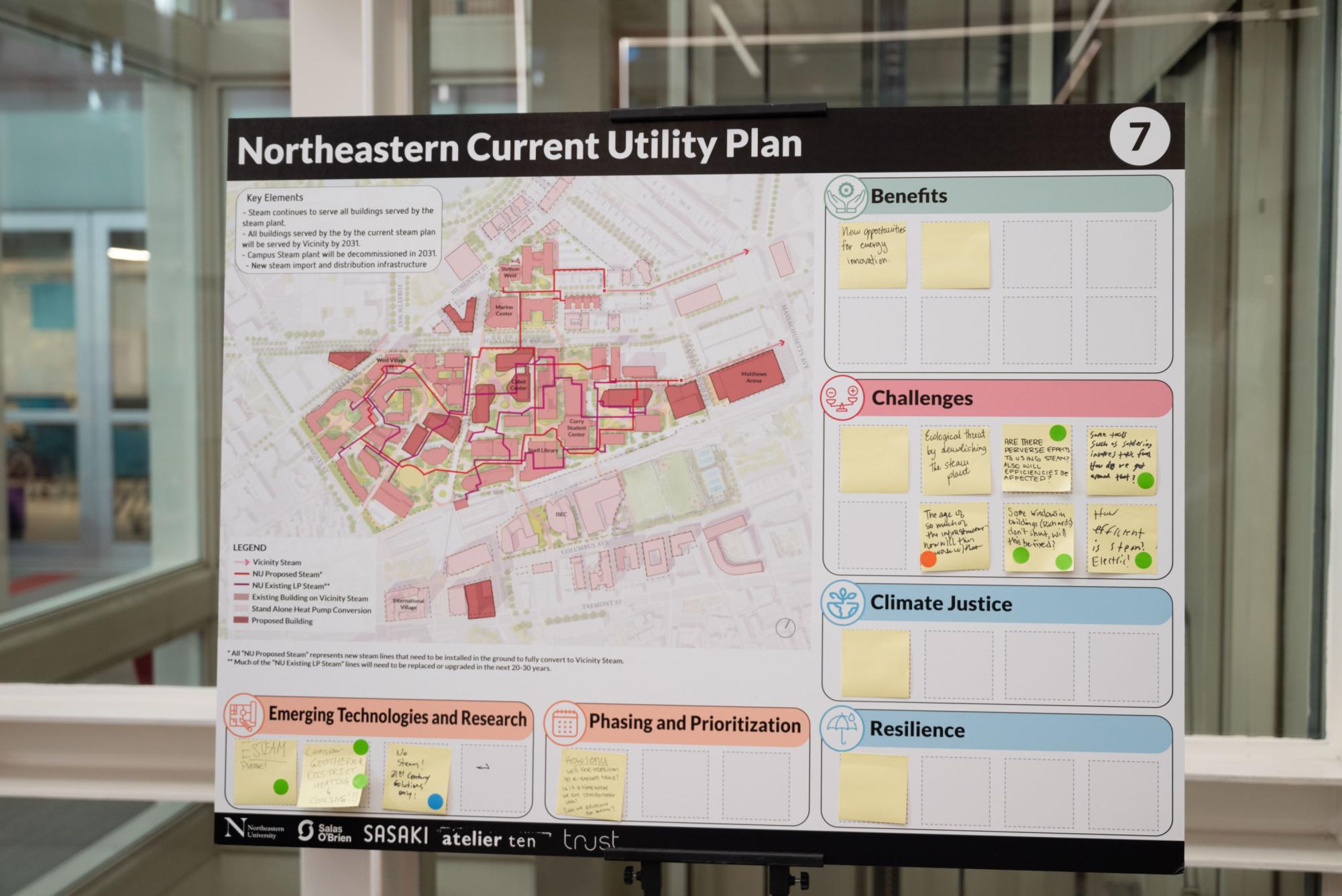

For now, events like the Decarbonization Community Forum, which took place in November 2024, have been open to all, providing more information on the university’s specific decarbonization while welcoming public feedback.

“I think Northeastern is being really receptive to how students are perceiving the plan and I think they’re doing a great job reporting that feedback back to Planning Real Estate and Facilities,” Molloy said. “[Although] we’re not part of those sessions, I think they’re doing a great job of making us feel like our voices are heard in this process.”