For Laura Gersch, election night last year was “horrifying.”

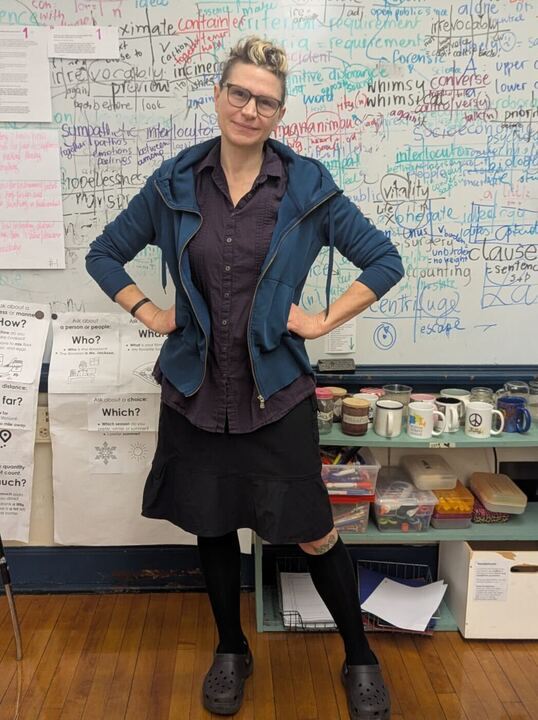

Gersch, a 10th grade English teacher at Boston International Newcomers Academy, or BINcA, a Boston Public School in Mattapan for English learners, spent the night anxious that she would wake up the next morning to news that Donald Trump had been announced as the 47th president of the United States. Her anxiety wasn’t for herself — it was for the safety of her students under the new administration, many of whom are immigrants and refugees.

Gersch’s fears quickly materialized. During Trump’s first week in office, his administration swiftly enabled immigration authorities to make arrests in schools, churches and hospitals, formally considered sensitive locations safe from arrests. Videos of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids in Boston began circulating on social media and soon reached Gersch’s classroom. As a teacher and immigrant herself, she has taken on the responsibility of keeping her students focused despite the impending dread of new policies.

“I tell them school is a safe place. We’re going to be okay. We can protect you,” she said. “All of which is not true.”

Every day, Gersch navigates teaching English to students from over 40 countries in the wake of political instability under Trump’s presidency.

“I think this is just very confusing for some students,” said Katrina Newfell, a high school program specialist at BINcA. “It has been very obviously upsetting.”

Cynthia Carvajal, the Director of Undocumented and Immigrant Student Programs at the City University of New York, reiterated a similar sentiment.

“The combination of the first Trump administration, the COVID pandemic and now the second Trump administration can be so emotionally and mentally debilitating for young immigrant folks who are just trying to get an education and participate civically, economically or socially in this country that they call home,” Carvajal said.

Despite the stress another Trump presidency brings to her students, Gersch refuses to shy away from political discussions.

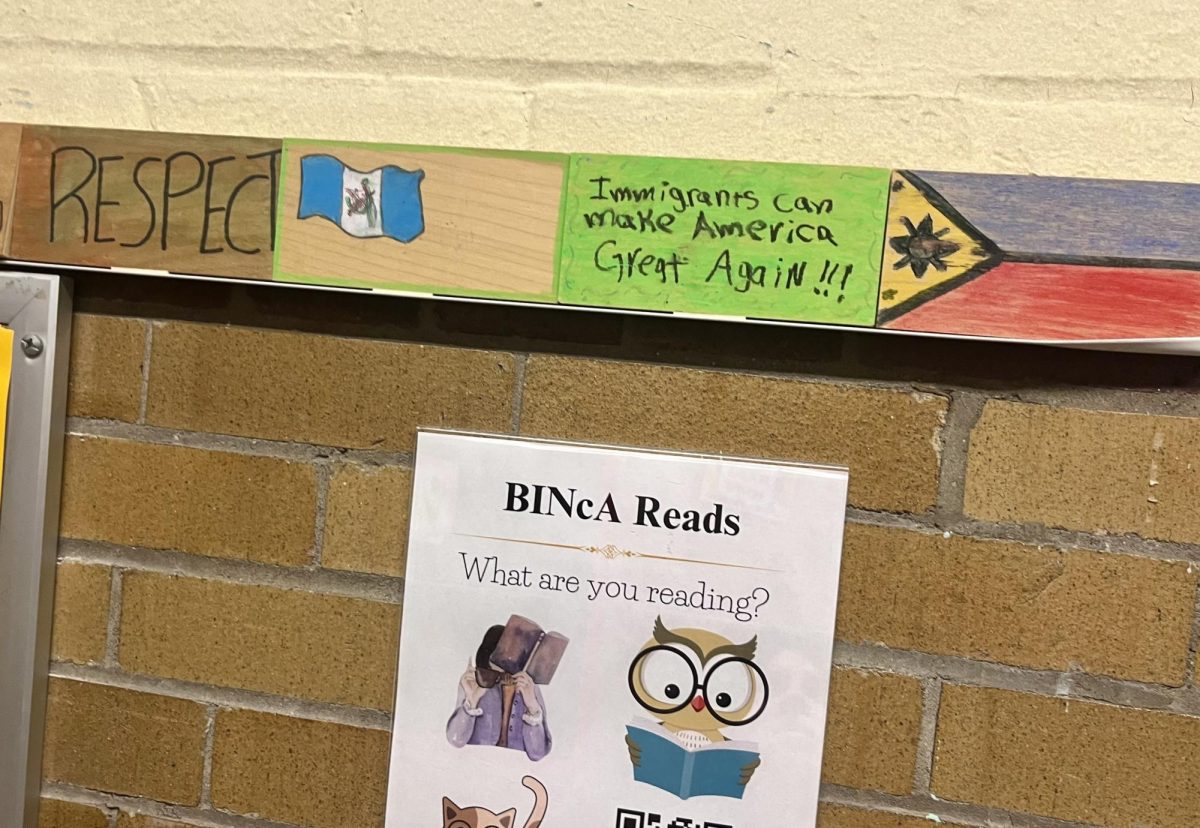

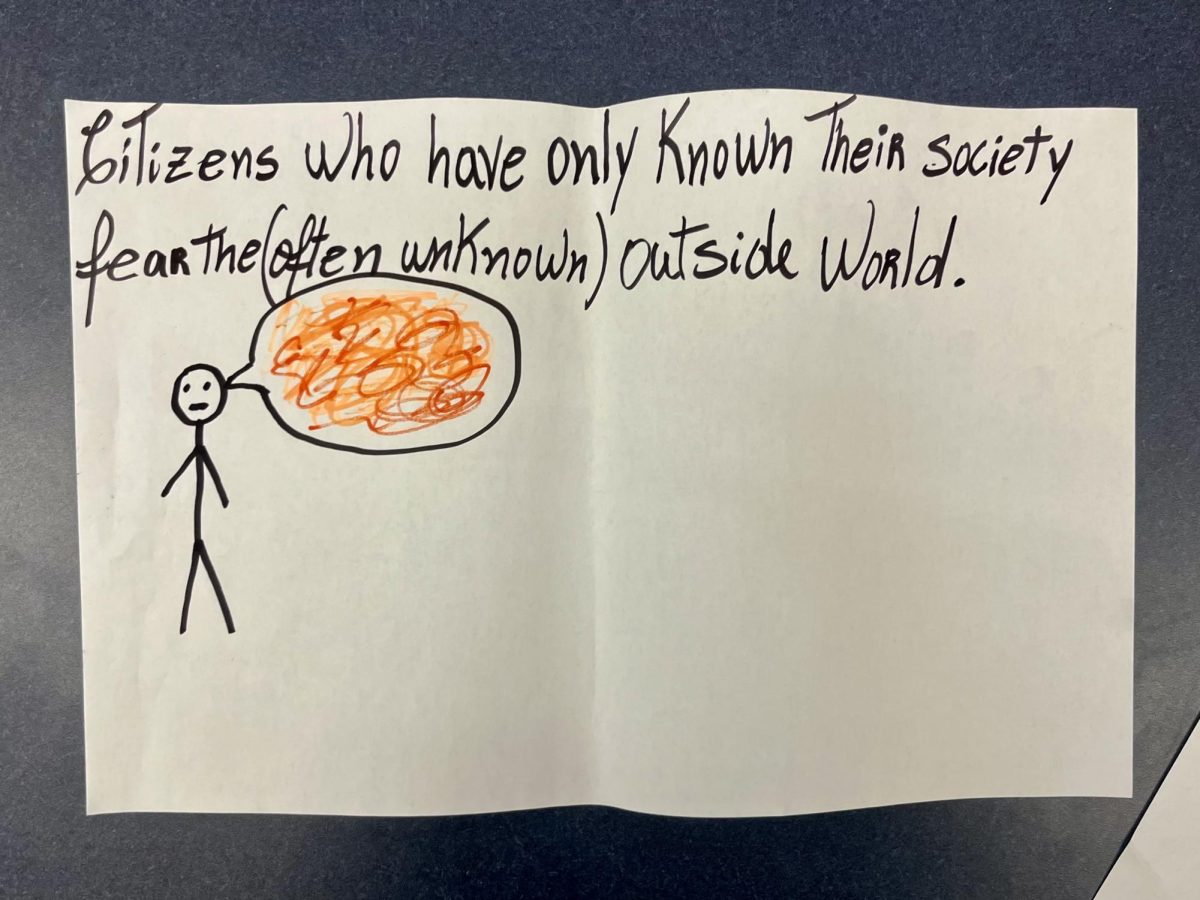

A recent project in Gersch’s class asked students to identify the elements necessary to recognize a dystopian world, a nod to Ray Bradbury’s 1953 novel “Fahrenheit 451,” the class’s current assigned reading. “Citizens who have only known their society fear the often unknown outside world,” wrote one student in cursive sharpie.

Now 51, Gersch spent her childhood hopping from country to country. Born in Munich, a city she still considers home, she came to the United States to study anthropology at the University of Massachusetts Boston. Unlike many of her students, she was not running from places overrun by war, gang violence or political turmoil.

“Many of the students who are here aren’t here because they think the United States is awesome. They’re just here because the place where they’re coming from is dangerous, scary, not manageable or all of the above,” she said.

Gersch began her career in translation and interpretation but yearned for less solitary work. She soon recognized that teaching was a powerful way to learn about others, particularly with multilingual students who could teach her about unfamiliar places. With English, Spanish, Italian, German, French and Haitian Creole already under her belt, she is focused on mastering the remaining languages spoken by her students, like Ukrainian, Arabic and Vietnamese.

Gersch embraces honesty with her students. She often tells them that getting a job or pursuing higher education can be more difficult for migrant students, especially if they’re undocumented. But she also encourages them to pursue their goals.

Though she can be tough with her students, she is patient and fair.

“Ms. Laura The Logical,” reads a sign near her desk.

Her day begins at 5 a.m., where she completes her daily Duolingo lesson. After school, she organizes a Haitian Creole class for staff in the building, where students themselves teach. By 8 p.m., she is able to grade work and finish any additional administrative tasks. On the rare occasion she must miss a day of school, her students know well in advance and have pre-prepared material to tackle.

Although she didn’t initially envision herself teaching, there is nothing she’d rather be doing.

“We’re in it together,” Gersch said. “In spite of all the pressures that come from the outside, we all have to endure this similarly.”