When asked how they consume the news, 16-year-old high school student Emma Israel, 22-year-old community college student Aubrianna Rin and 18-year-old Northeastern business administration major Alexis Matthews all said the same thing: Instagram.

These three Gen Zers are not alone. Roughly 50% of the generation relies on social media for the news. Instagram, the Meta-owned social media company, is the primary source of social and political information for half of those born from 1997 to 2012, according to Statista. A recent change to Instagram’s algorithm, however, may keep this crucial voting block in the dark this election season.

Instagram announced in February that it would stop “proactively” recommending political content to users, an update that also applies to Threads, a newer Meta app that is less popular with Gen Z. What Instagram did not announce to its users is that “political” and “social” content would be limited by default.

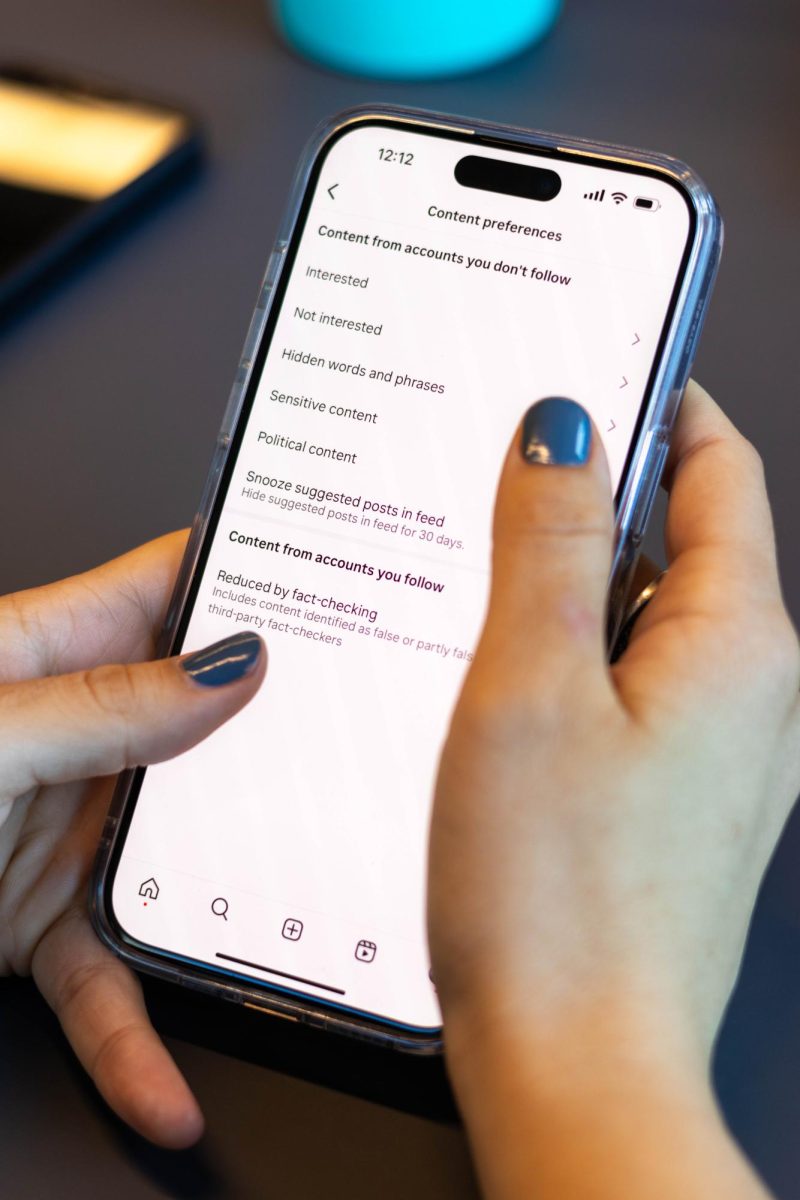

In mid-March, Instagram users noticed a new feature in their content preferences: a little blue dot next to the words “limit political content from people you don’t follow.”

“When I finally went into my account settings, I noticed Instagram had been limiting political information in my suggested content,” Rin said.

Some users are now accusing the company of censorship during an important presidential election year in the United States. Others worry this update will impact how young voters stay informed in the digital age.

For years, Instagram has had presets for various content preferences that apply to the main feed, Reels, the Explore page and suggested users. Users can manage the amount of sensitive content on their feed, flag specific posts as interested or not interested and even limit content through words and phrases.

Preventing Instagram from limiting “political” and “social” content is as easy as pressing a button. What concerns many users about the update is that Instagram did not properly announce this setting would automatically go into effect.

“If I knew Instagram was implementing this change, I would’ve turned off the limitations sooner,” Rin said.

Instagram co-founders Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger never intended for the app to be a prominent news platform when they initially created it in 2010 as purely a photo-sharing service. Meta has since received heavy criticism from users for allowing political content to dominate peoples’ feeds.

“One of the top pieces of feedback we’re hearing from our community right now is that people don’t want politics and fighting to take over their experience on our services,” Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg said during an earnings call in January 2021.

In a February 2024 press release, Meta announced why the newest update occurred: “We want Instagram and Threads to be a great experience for everyone. So we’re extending our existing approach to how we treat political content – we won’t proactively recommend content about politics on recommendation surfaces across Instagram and Threads.”

Meta has also accumulated significant blame in recent years for Instagram’s role in spreading misinformation and growing online extremism during the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections. The company has since been “working for years to show people less political content,” Dani Lever, a spokesperson for Meta, told TIME in March. However, political content creators are worried about Meta initiating this update without a direct notification during a pivotal election year.

“You can’t just essentially put a blindfold on people who may not realize it. A lot of people don’t even know that this is a thing that’s been applied to their preferences,” said Johanna Toruño, a popular artist and Palestinian advocate on Instagram, in an interview with NBC News in March.

Meredith Clark, an associate journalism professor at Northeastern and the founding director of the Center for Communication, Media Innovation & Social Change, explained that exposure to the media is historically crucial to facilitating public opinion and social change. Social media is the latest chapter in influencing the political climate and systemic progress, she said.

“With social media, I see the ability for people who ordinarily wouldn’t be heard to have their voices heard more often and louder than they might have been in previous media eras,” Clark said.

Instagram is known for being a mecca of diverse voices, as users can access nearly unlimited information and opinions. In the marketplace of ideas, having more voices results in a “richer” debate and discussion, Clark said, and that a “social movement requires a vision that is clear enough for multiple parties with different interests to commit to.”

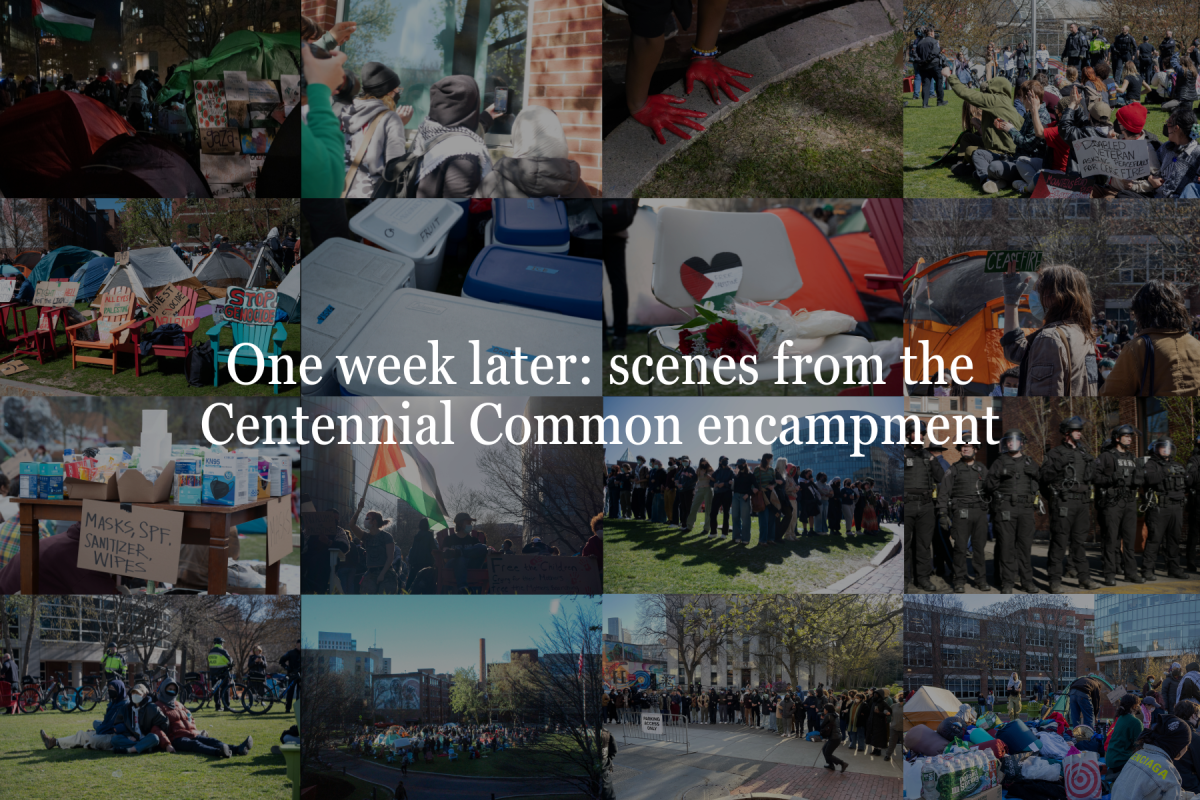

Social media’s ability to share information and unite different people over common issues can be seen across the world, from Twitter’s #MeToo to Instagram’s #BLM, Clark said. She went on to say that a lack of access to political content threatens how Americans work toward social progress.

“Social media can disseminate information at a scale that is not possible with other media tools,” Clark said. “It allows people and messages to cross boundaries — physical boundaries and political boundaries.”

The update to Instagram’s algorithm also threatens how Gen Z consumes media and how advocates promote their causes. Many interest groups and political organizations, such as Greenpeace or March for Our Lives, utilize Instagram to inform the public and update members.

Mimi Yu, a third-year computer science and political science combined major and treasurer of Northeastern’s Feminist Student Organization, said that limiting political content on Instagram will negatively impact the organization’s advocacy efforts. The club hosts discussion-based meetings for various societal issues women face, as well as volunteering and fundraising initiatives.

“Our main way to contact members is through Instagram,” Yu said. “It’s the easiest way to reach the student population.”

Even though political content creators and their followers have concerns about what will be censored, Meta has yet to clarify what exactly constitutes political content beyond its broad definition: “potentially related to things like laws, elections, or social topics,” according to NPR.

“The content that we post is not inherently political … but I think the very nature of being feminist is political,” Yu said. “If anything that could be seen as a divisive issue is limited on Instagram, that’s concerning because it’s our main way of reaching our audience.”

This is a broad concern among Instagram creators whose posts may be flagged as political, as many users are unaware of the change to their algorithms. Several notable publications, such as the Washington Post and The New York Times, posted instructions for turning off limitations on their Instagram accounts.

“Successful social movements require [media],” Clark said. “Without it, people don’t get the messages they need to understand what’s happening, why it’s happening and how they can either be a part of it or what it might mean to resist it.”

Social media has become integral to Gen Z’s political socialization. In the digital age, social progress can begin with a post on Instagram.

“Given the current presidential election, it’s really important for young people to be more politically active than ever,” Yu said. “For us, that advocacy looks like social media.”