By Hsiang Yu Wu, news correspondent

Nearly 400 years ago, Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijnand and Johannes Vermeer created art to comment on the social strata of Holland. Now, that art makes its temporary home in Boston.

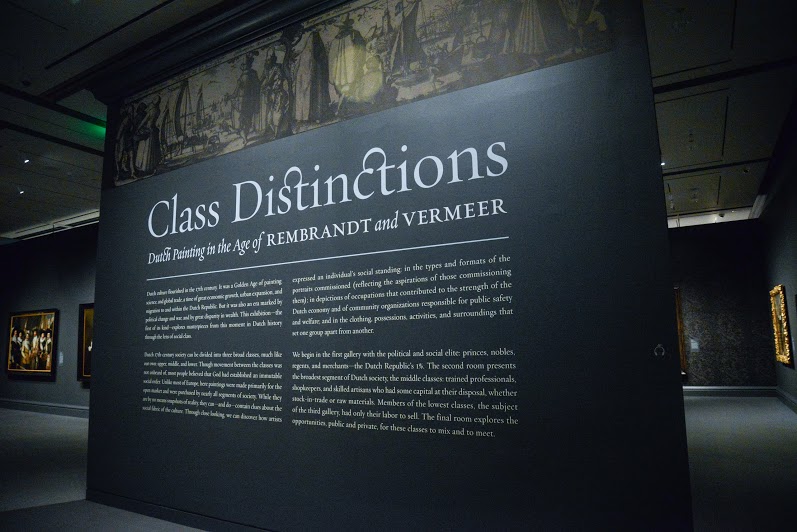

Class Distinctions: Dutch Painting in the Age of Rembrandt and Vermeer previewed at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) on Monday. Reflecting the observable class differences in 17th Century Europe from the Dutch painters’ perspective, the exhibit shows an early form of socially motivated art. The exhibit opens Oct. 11.

Ronni Baer, senior curator of European paintings at the MFA, said she wanted to approach art from the past with applicability to the present. By focusing closely on the depicted people’s behavior, clothes, movement and background, class distinctions reveal themselves across the centuries.

“[The paintings] help tell the story in the way that no other painting could,” Baer said. “Many pictures require close looking, encouraging the viewer to differentiate between a mistress and a maid, or to distinguish a noble from a social-climbing merchant.”

The exhibition includes 75 Dutch masterpieces provided by museums across Europe and North America. Forty-eight different artists are represented and 24 paintings make their US debut. In addition to showcasing the works of Rembrandt and Vermeer, the exhibition features portraits, genre scenes and landscapes from their Dutch contemporaries, including Jan Steen, Frans Hals, Pieter de Hooch, Gerard ter Borch and Gerrit Dou.

The exhibition is divided into four main categories: art of the upper class, art of the middle class, art of the lower class and the intersection where the classes met.

“We looked carefully at what paintings we wanted to consider,” Baer said. “We traveled to see them all. We had to make sure they were the quality and the condition that we wanted for the exhibition and that they helped tell a story in a way that no other painting could.”

Dutch painter Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt’s “Maurits, Prince of Orange” depicts life of the upper class, as William of Orange’s royal descendent stands in golden armor with a silken sash. Though not always to this extreme, the upper class is depicted wearing the highest quality clothing and enjoying life’s luxuries in the featured 17th Century art. Scenes showing men studying sciences in leisure and the women reading and writing in their studies communicate a higher distinction of life.

The paintings of the middle classes, comprised mostly of goldsmiths, craftsmen and shopkeepers, show daily life. One masterpiece of the middle classes is Rembrandt’s “The Shipbuilder and his Wife.” A shipbuilder works on his navigation as his wife comes into the room to give him a note. Most portraits of the period did not depict men and women interacting, making this painting unique because of the moment shared between husband and wife, according to Baer.

Another portrait shows a mother training her daughter in domestic living, as seen in de Hooch’s “Interior with Women beside a Linen Cupboard,” showing both strict gender structures of 17th Century Europe and artists’ fixation with domestic living, Baer said.

Baer went on to explain that although middle class people appear well-dressed, the quality of their clothing is not comparable to the luxury of the upper class.

The lower-class paintings are usually scenes of poverty and hard physical labors. Ter Borch’s “The Knifegrinder’s Family” emphasizes darker hues. A man carves a knife under a wooden roof as his wife sits in the frame of a dilapidated building tying a sack together, a scene that would never be seen in any upper strata.

The final room of the exhibition presents the situations that place the various classes together. Ochtervelt’s “Street Musicians at the Doorway of a House” shows the perspective of a middle class family who provides charity to beggar children. A woman reclines in a chair as her maid deals with the urchins. The little girl gives charity to the poor street musicians dressed in drab rags.

“The classes, how the people lived, where they were, it is all there,” Jack Curtis, an attendee from Brookline, said. “And so I think after this people will look at paintings in a different way.”

Aside from the paintings, the final room features a selection of decorative arts over the three classes. On each table, there are different glasses, pitchers and linens that people can find distinct and identifiable to each of the classes.

“The exhibition is wonderfully conceived and beautifully presented,” Curtis said. “It really answers the question of what do paintings tell us about the time.”

Photos by Scotty Schenck