By Sophie Cannon, managing editor

A whirlwind of clothes hitting the floor, limbs tangled in bedsheets too small for the dorm-sized beds and an ad-free Spotify playlist in the background. As depicted by the many romantic comedies and teenage television shows, this is a common scene of the college-aged love life.

What is missing from this impassioned event? The discussion around sexually transmitted infections, or STIs, and use of contraceptives. Unfortunately, this is not just the case in the movies, as many students are also either not aware of the risks that come with unprotected sex or the fact that STIs are on the rise in their demographic.

There were a reported 2 million cases of STIs between the years of 2015 and 2016, according to a new Center for Disease Control (CDC) report comparing rates of STIs between those years. Of those cases, 1.6 million were chlamydia, which is most often found in young women. Syphilis, which is most often found in men who have sex with other men, saw a 36 percent increase in young women over the one-year period the report covered. As STIs rise, many do not know the types of questions to be asking, nor the places to go to ask those questions and get information on STIs and sexual health.

“What’s interesting about Northeastern is that there is such a diverse group of students with various backgrounds of STI knowledge,” said Kathrine Gilmore, treasurer of NU Sexual Health Advocacy, Resources and Education, or NUSHARE, and a fifth-year communication studies major. “For whatever reason, sexual health programming kind of stops when you get to college. We don’t have a women’s center on campus, and most colleges do. We don’t have anything sectioned just for sexual health.”

With the rise of STIs in the college demographic, the lack of a reliable resource center for testing, sexual health questions and advice exacerbates the problem and makes it harder for students to become informed or deal with an existing STI. While the University Health and Counseling Services, or UHCS, is a resource, many students do not know what the office provides in terms of STI education and testing. UHCS does offer STI testing, however according to a poster in a locked back room in UHCS, each STI test costs $25 and must be paid for out of pocket. After being contacted by email and by phone, UHCS declined to comment.

“UHCS is not open with the fact that they charge, so every year we have to research what they charge,” Gilmore said. “When we talk about resources, people are surprised that they even offer it.”

University spokesperson Matthew McDonald said in an email to The News that the health of Northeastern students is the university’s highest priority.

“University Health and Counseling Services provides the university’s more than 20,000 undergraduate and graduate students with confidential, compassionate, and high-quality care throughout their college experience,” McDonald said. “Preventative care, including sexual health counseling and STI testing, is available to students through UHCS.”

The rise in STIs affects the city of Boston as a whole, where college students make up a large portion of the population during the school season. Samantha Johnson, a program manager for the prevention and screening division of the Boston Medical Center, noted the rise in STIs in her college-aged patients.

“We have seen an uptick in chlamydia and gonorrhea,” Johnson said. “They have always been very common, especially inside colleges. Tight-knit groups, such as in college, have that as the most common form of disease. These diseases can pop up if you are not getting tested between partners.”

Another effective way to prevent the spread of STIs is through barrier-method contraceptives, most commonly the condom. This too comes with an unfortunate stigma, as many sexually active couples do not use contraceptives aside from the oral pill or intrauterine device, which do not protect against STIs. According to Men’s Health magazine, in the most recent National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior less than half of men ages 18 to 24 used a condom the last time they had penetrative sex.

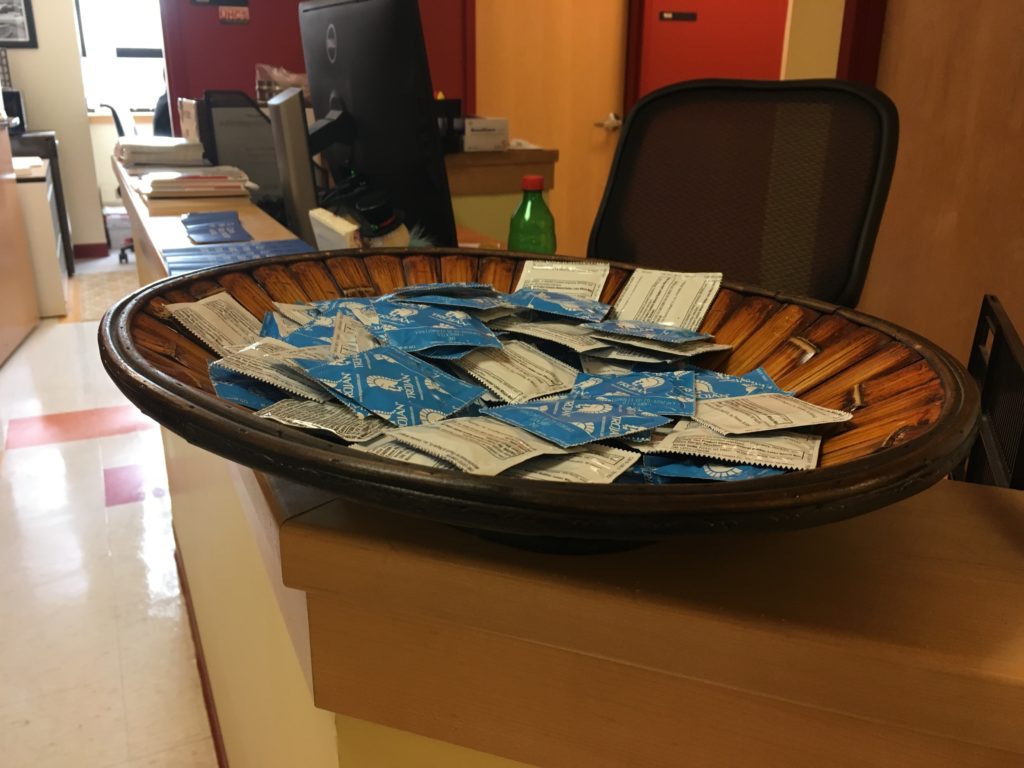

“We are strong proponents of the condom,” said Colin Thompson, co-coordinator of the campus health advocacy group Peer Health Exchange and a fourth-year environmental science major. “It covers the bases, it is cheap and accessible. But there is the social stigma. It’s hard to walk into the drug store and buy condoms or reach into a bowl to get them; it’s become a joke almost. We have to focus on ending the stigma and shifting the conversation and making it a more common conversation.”

The image of a nervous teenage boy or girl at the drugstore counter asking for condoms is just as common of a scene as the steamy college dorm room, and is yet another barrier to getting rid of STIs on campuses nationwide. While stigmatized, condoms are also often discarded because one partner does not want to use them.

“We have a lot of guys that don’t enjoy using them so they don’t wear them,” Johnson said. “Women also don’t know how to negotiate with their partners on the condom front. In our field we do condom negotiation workshops where we teach and empower partners to be able to advocate for their own sexual health needs. When you come in to get tested at a public health clinic, they provide that. Unfortunately, not everyone goes to a public facility.”

Bridget Brunda, a fifth-year health science major and another co-coordinator of Peer Health Exchange reminds her mentees that condom use is not just for traditional penetrative sex, something else she said students have a misunderstanding or lack of education about.

“All types of sex, including oral, come with the risk of STIs,” Brunda said. “Even making out can transmit herpes. We need to think about how we are conducting ourselves.”

Providing those barrier methods, specifically condoms, to Northeastern students is also a challenge within itself.

Gilmore, who was an RA for a freshman dorm last year, tried to provide condoms to her residents during a sexual awareness program she planned. UHCS and her RA supervisor refused to fund her program, making it all the more difficult to provide contraceptives to the student body free of cost and stigma.

“I did a sexual health program and wanted to have condoms to back that up,” Gilmore said. “[UHCS] told me absolutely not, and made me very uncomfortable so that I didn’t even grab a handful for myself.”

Gilmore added that for the individual student who wants to go to UHCS for free condoms, they have now moved the bowl from the lobby to behind a door.

“If you want them you have to go in as if you have an appointment, and then go back out. It’s the extra burden and embarrassment just to be safe,” she said.

Without proper sexual health education, turning the CDC report’s results around for the next yearly study proves very difficult. Sexually active students must know when and how to use protection, feel comfortable enough to advocate for condoms, have the finances available to get tested if on campus or the knowledge of where else to go for free. Then, with every change of partner or health condition, do it all over again.

“We try to foster introspective thought, but it can be difficult in our age group,” Thompson said. “Public health has always been hard to instill any form of behavioral change. If they don’t want to change, they won’t. What we focus on is telling them about the contraceptives, but you should be going and using the knowledge of yourself and your body to make the most informed decision.”