Study suggests police-worn body cameras are effective

Northeastern University Police Department members received an award for raising more than $2,000 to support veteran readjustment efforts. / Photo by Paxtyn Merten

January 31, 2018

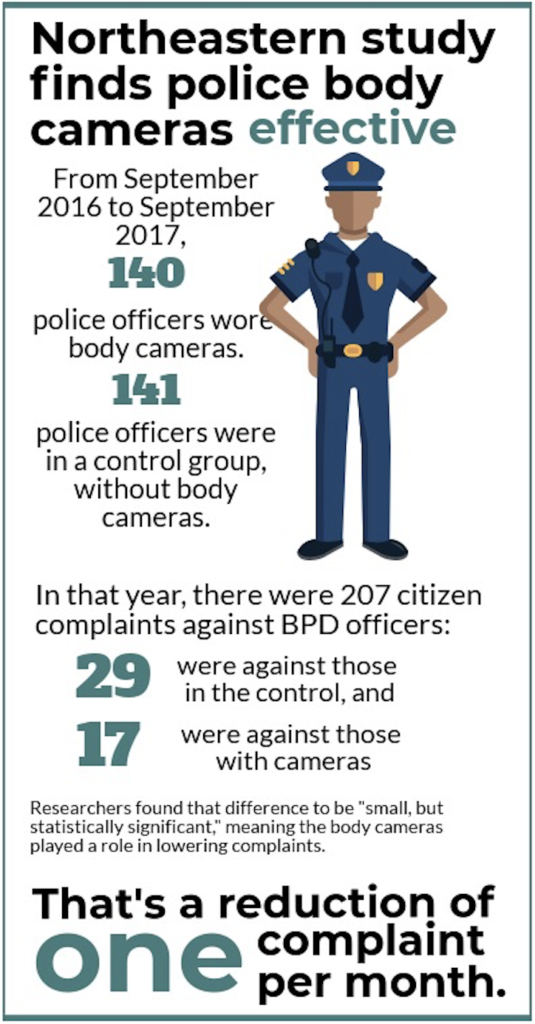

A Northeastern University study released in early January suggests that body-worn cameras result in a “small, but statistically significant” decrease in police misconduct complaints. The study has underscored civil rights advocates’ promotion of body cameras, but those familiar with the issue approach it with caution.

The study was based on a body camera pilot program in which the Boston Police Department randomly selected 140 officers to wear cameras and another 141 officers for a control group. The study, which lasted from September 2016 to September 2017, produced results that have independent groups like law firms and civil rights organizations advocating for wider implementation of the cameras.

During the pilot program, there were 207 citizen complaints made against BPD officers. Twenty-nine were against the study’s control group of officers without cameras, and 17 were against the camera-wearing officers.

The issue comes during an era in which police misconduct has been under intensified scrutiny nationwide. Boston is behind many major U.S. cities in police accountability improvements; the list of cities with some kind of body camera program includes Atlanta, Chicago, Denver, Houston, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Phoenix, San Francisco and Washington, D.C.

Body cameras were a key subject in an Oct. 24 debate between then-mayoral candidates Mayor Martin J. Walsh (D) and former City Councilor Tito Jackson (D-7). WGBH, which hosted the debate, said their polling revealed that 78 percent of likely Boston voters favored the use of the cameras, while 12 percent opposed.

“Once the [Northeastern] study comes back, we’ll make the decision on what the next step is,” said Walsh, who went on to win the election. “It could be to have them.”

“There was great interaction in the community,” Walsh said. “There were a couple suggestions where there were incidents in neighborhoods where actually police officers called for somebody with a body camera to come. So that’s all positive.”

Walsh’s office declined to comment on the matter last week, saying the mayor will wait for the full report’s release in June.

Jack McDevitt, a principal investigator on the Northeastern study and the associate dean for research in the NU College of Social Sciences and Humanities, said he also wouldn’t comment on the study until its full release but that he thinks there are ways for police to improve conduct aside from cameras.

“Things like additional training and more strict protocols can improve conduct,” he said, “not just cameras.”

He attributed a significant drop in BPD conduct complaints after 2013 — there were 360 complaints in 2013, compared to 207 during the pilot program — to investment in officer training.

Howard Friedman, a Boston lawyer whose firm brings civil suits on behalf of victims of police brutality and other civil rights violations, strongly favors body cameras being implemented in the city.

“It would provide more information about what police are doing,” Friedman said. “When police misconduct occurs, the public has a right to know what happened, and we have the technology to do that.”

Friedman said the cameras are a needed piece of evidence in cases where defendants have no other chance to have their account heard.

“Without cameras, these incidents turn into a swearing contest between the officer and the suspect, and when it’s the officer’s word against a civilian, the officer wins every time,” he said. “People should be able to see what really happened.”

Friedman criticized BPD for failing to implement an officer early intervention system, which would flag officers with a relatively high number of complaints.

“They were supposed to do that in 1992,” he said. “You’d think they would’ve had time to do that by now. That system would flag officers with a large number of complaints, without the complaints needing to be proven. So an officer with 15, 20 complaints, somebody would say, ‘Hey, maybe there’s an issue here.’ … There are still problem officers patrolling the streets of Boston.”

Rahsaan Hall, the director of the racial justice program at the American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts, said body cameras would be a good step, but only if certain precautions were taken to protect people’s privacy.

“We need to make sure that the video that is captured is not intrusive to people’s privacy,” Hall said. “We need to protect video that may be taken inside people’s homes, that may put people in compromising positions. There would need to be a strong policy that keeps citizens protected.”

Hall specified that he would hope to see precautions taken against the cameras being used for biometric scanning or facial recognition. He said tape not being used in a complaint case should be destroyed in “a reasonable amount of time.”

An ACLU position paper supplied to The News by Hall suggests limiting officer discretion in turning off cameras, disciplining officers who violate policy and requiring officers to write a report before seeing footage.

Like Friedman, Hall said he doesn’t see the cameras as the be-all-end-all in police conduct improvement.

“The ACLU sees the cameras as important, but not as a panacea for all policing issues,” he said.

John Farrell, a Northeastern University Police staff sergeant in the crime prevention unit, said body-worn cameras would not foster an improved relationship between police and citizenry.

“If their reasoning is that they don’t trust their police officers — whom they vetted and hired — to consistently uphold the constitutional rights of the civilians whom they are sworn to protect and serve and these [cameras] will better ensure that officers behave in a manner consistent with what is expected of them, then that will not bring about a healthy communal relationship in the long term,” Farrell said in a Jan. 27 email to The News.

Farrell said treating cameras as a revolutionary source of accountability is risky, because they present only one point of view of an incident and can leave out important angles or sounds. He favors a less quantifiable, more trust-heavy approach to improving police-citizen relations. He said it takes hard work from both parties, but his NUPD has found success.

“In order to attain and maintain safe and secure communities, there must first exist the honest desire on the part of the police and community members to engage with one another and work together on building stronger communities,” Farrell said. “Like with all good interpersonal relationships, it takes continual work to keep it healthy and strong. It is to be expected that there will be ups and downs in communal relationships. There will be good and not so good times and there will be compliments and complaints.”