By Thomas Herron, sports columnist

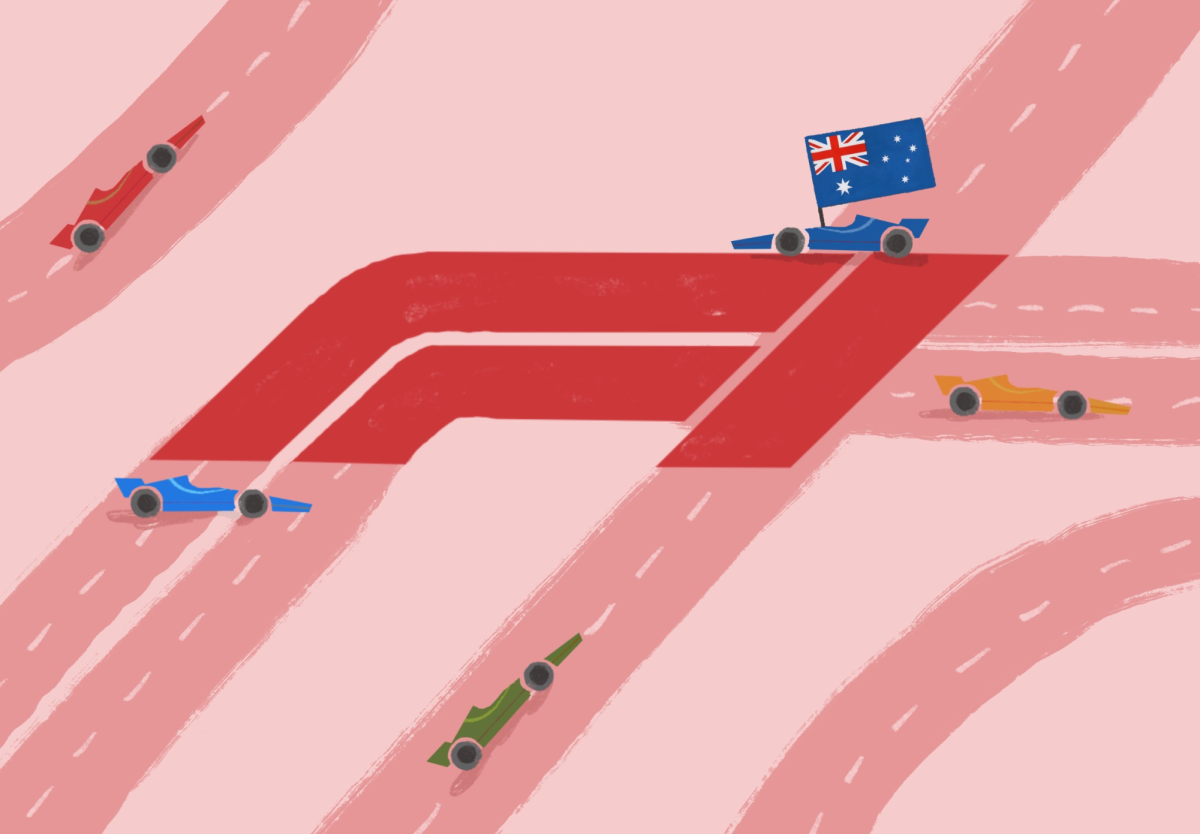

For almost every school with an athletic program, whether it is a top-tier organization that is competitive in every sport or a small school that only offers a couple of sports, athletics bring in substantial sums of money. The interest in college sports is obvious: The NCAA brought in $1.06 billion dollars of revenue in 2017 through ticket sales, merchandise and TV air time.

It is no secret that the NCAA profits off of student-athletes, and in theory a lot of that money goes back to their schools. But why doesn’t this money make it back to the players who inspire interest in the programs?

Student-athletes should be paid. The way the United States economy works makes it clear that athletes should see some sort of monetary gain from the money they bring in to schools, conferences and the NCAA as a whole. It feels like a basic principle of capitalism; if their work brings money in, they should see some of it — right?

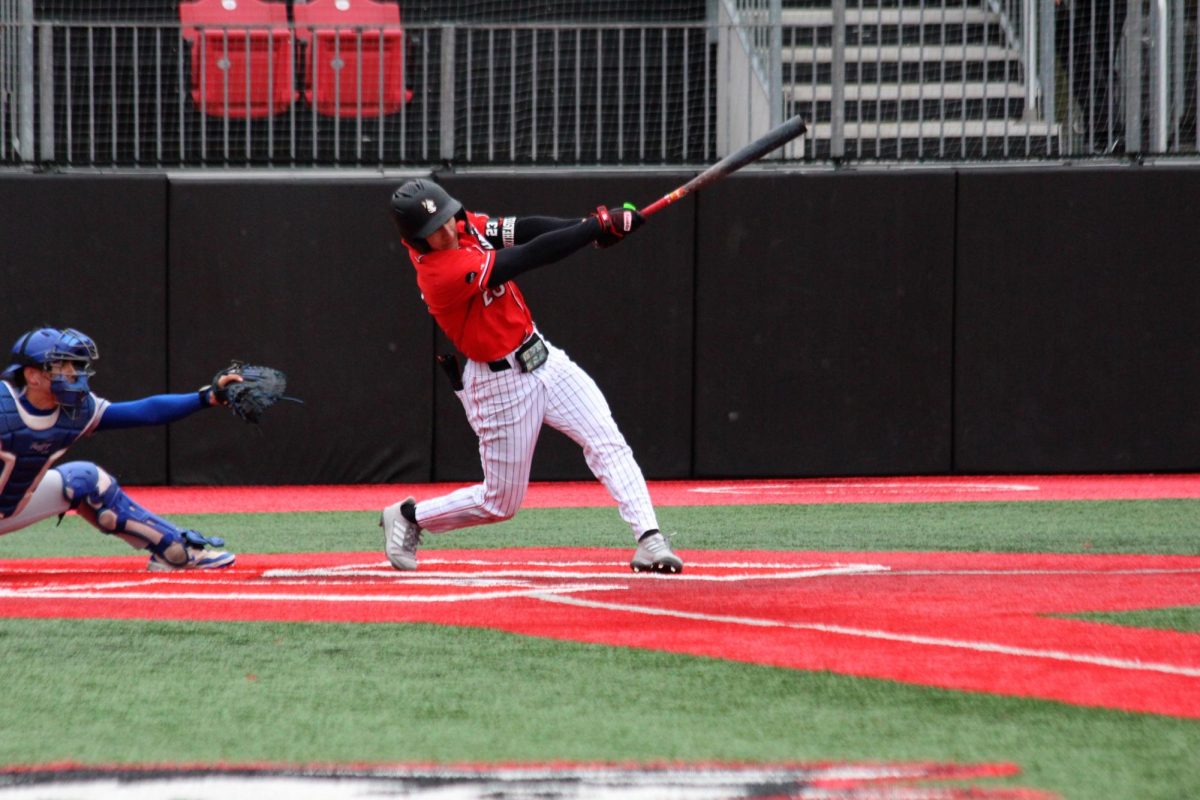

The argument that student-athletes do get paid in the cost of tuition, room and board, books, etc. is bogus. For some athletes that is true, but it’s still not remotely a fair trade. Even at the most expensive schools, cost of attendance is about $70,000. Some college athletes double that annually in jersey sales alone, so full rides — which are much rarer than popular belief — can be scraps of someone’s worth.

Take Johnny Manziel for example. Manziel attended Texas A&M University for three years and played for two seasons. He brought in $150,000 in sales of jerseys with his number on them at the university’s bookstore alone. Not to mention the NCAA’s online store and the money the team’s performance raked in through appearances in prestigious games and marketing revenue.

Manziel received an athletic scholarship and since football is a “head count” sport, all scholarships are full-ride. He was at A&M for three years, and as a Texas resident his total cost of attendance would have been $27,452 per year, coming out to a total of $82,356. This pales in comparison to the estimated $44,620,000 he generated for the school’s athletic department. The school paid him approximately 0.19 percent of his worth.

But what about everybody else? Only about a third of NCAA athletes ever see an athletic scholarship, and the average scholarship award for athletics is less than $11,000. An $11,000 average scholarship isn’t great, especially for athletes who can generate millions in revenue single handedly.

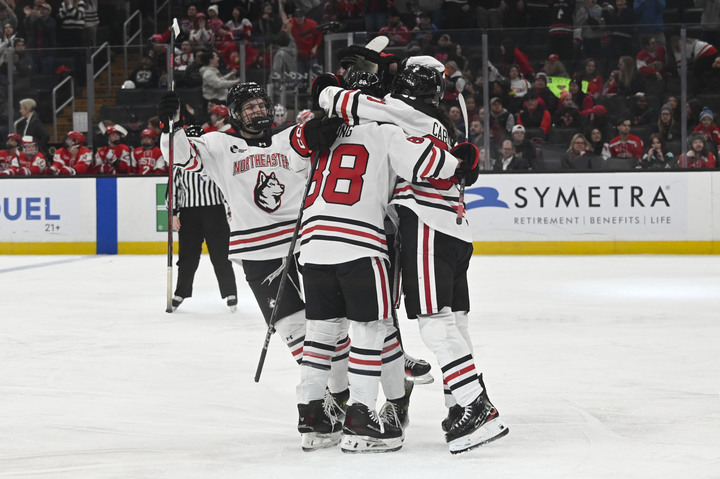

College athletes are putting their bodies on the line to play for their school. Even if they do not all have a revenue-generating level of star power, they all play their part in the success of a program and the resulting monetary gain.

When the NCAA partnered with EA sports to make a video game based on college football, it featured characters that closely represented real-life players. Robert Griffin III was on the cover of NCAA Football 2013, so it’s hard to believe the nameless Baylor quarterback who looked and played exactly like him — and wore his number — wasn’t based on him. For the NCAA to not allow players to get a payout from this and their likeness is borderline theft.

Just because you list Robert Griffin as “QB, #10” doesn’t mean kids aren’t still picking Baylor to play as him. And if that’s a reason that the game sells and the NCAA and EA sports — two for-profit organizations — are making money, why in the world shouldn’t Griffin see some of it?

The fact the game was discontinued should make it clear that the NCAA knows it’s wrong to make money off these players without letting them see any of it. The NCAA football video game has discontinued, but adds to a bad track record of the NCAA exploiting their top student athletes.

Failing to pay student-athletes results in the violations we see now, with student-athletes accepting payment from sports agencies trying to recruit them. ASM Sports violated NCAA rules when it paid future #1 pick Markelle Fultz $10,000.

The crazy part is the $10,000 Fultz received illegally is a tiny fraction of his value, but to see any sort of compensation for the money he generated, he had to break the rules.

College athletes should not be paid millions, or even relatively similarly amounts to the level professional athletes are compensated. But if a single athlete such as Manziel can be proven to bring in millions of dollars, and is not being compensated for any of it, he should at least be allowed to pocket some autograph money.

If the NCAA were to adopt some sort of fractional payment system for athletes who generate substantial revenue, it could lessen the likelihood that athletes accept under-the-table payments from fans and agents, and therefore avoid some of the problems we’ve seen unfold recently.