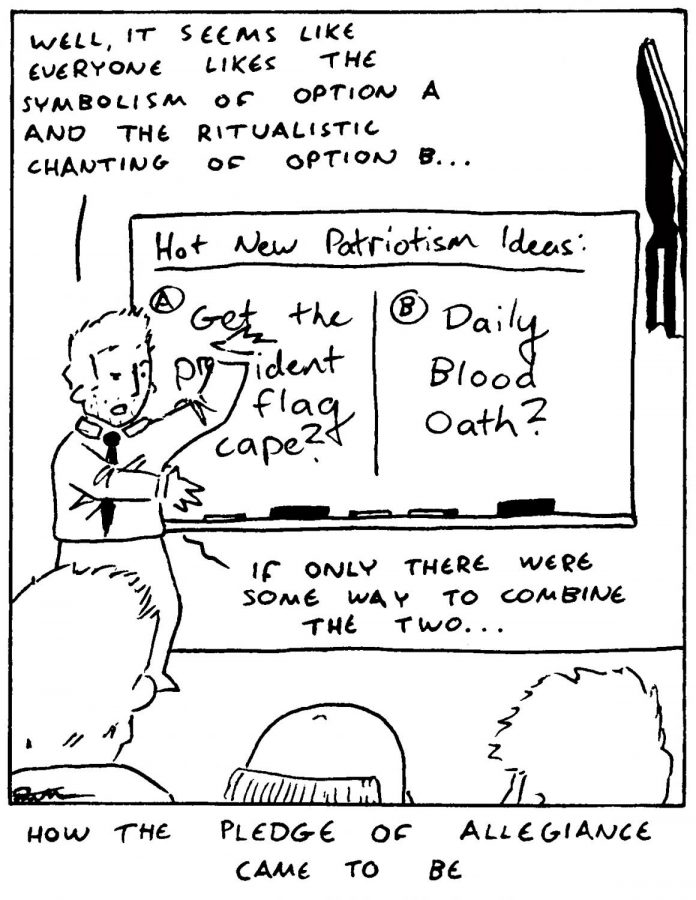

Column: Where does the Pledge of Allegiance belong?

Stand up, place your right hand over your heart and recite the Pledge of Allegiance…why?

February 2, 2019

She casually endorses religion, was born in 1942 and says things that are somewhat controversial. She isn’t your grandmother. She is the Pledge of Allegiance.

“The Pledge of Allegiance attempts to communicate a sense of patriotism regardless of what the country has done for the person saying it,” NU graduate student Katie Woods said.

Woods, a second-year graduate student pursuing a master’s degree in public history, studies how society constructs historical memories and ideas about this nation. She previously worked at Facing History and Ourselves, a nonprofit that promotes a curriculum to help students examine injustices and better understand their roles as citizens.

Although Woods acknowledges that the pledge “has a pleasant idea of liberty and justice for all,” she said “the reality is quite different than that.”

For 12 years, the Pledge of Allegiance began my every morning. Stand up, place your right hand over your heart and recite: “I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation, under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

I repeated the words drowsily and half-consciously, wishing I was still in bed. I thought very little of the words. I believed they were devoid of any relevant meaning, belonging to centuries bygone. Truthfully, in my mind, the 15-second chant was just 15 fewer seconds spent listening to my teacher talk.

Last July, I traveled to Sydney, Australia, for my first semester of college. Prior to each class, public event or community gathering there, a speaker would acknowledge the history of aboriginal people and their land. Pledges varied, but followed a form something along the lines of this: “I acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land on which we are meeting. I pay my respects to their Elders, past and present, and the Elders from other communities who may be here today.”

In 2010, the Federal Parliament formalized the practice.The president now recites the acknowledgment of country before all sittings, quorums and adjournments of the Senate. Reconciliation Australia, an organization which promotes justice and equity for aboriginal people, defines the acknowledgment of country as an “an opportunity for anyone to show respect for Traditional Owners.”

Two rituals, starkly different. Both take place in countries with democratic governments, powerful economies and perceived freedom. There is something bewildering about expecting students to say an oath in a seemingly “free” country, especially in one built by dissidents. Yet, in the United States, we do. Although a 1943 court decision ruled that students could not be forced to recite the Pledge of Allegiance, it still is a widely adopted custom.

According to the Massachusetts Commonwealth Title XII, Chapter 71, Section 69: “Each teacher at the commencement of the first class of each day, in all grades, in all public schools, shall lead the class in a group recitation of the ‘Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag.’”

The Australian model differs in that students are not expected to hymn along with the instructor. Rather than suggesting a “group recitation,” Australian students can take the time to silently reflect on the words being offered.

When I first experienced the Acknowledgement of Country at the University of Sydney, I attempted to compare it to the Pledge of Allegiance. My initial instinct was to question my patriotism. How could I ally myself with a country that ignores it’s brutal past? Meanwhile, Australia gives credit where it’s due. The most reassuring aspect of the Pledge of Allegiance is the last two words: “for all.” The question is, should that “all” be defined, as it is in Australia?

My answer to that question is based in my own experiences. It is not up to the government, but up to the students to recognize whose liberty they are standing up for. It is up to the history teacher to follow the pledge or the acknowledgment with a diverse and inclusive education to reveal to their students who that “all” refers to.

“It’s important that students understand the context. Teachers should have a larger discussion about what the pledge stands for,” Woods said.

I realize the United States is missing more than just an acknowledgement of all the communities who have been oppressed. Let’s face it, the list would be too long to fit into 15 seconds. Historical empathy takes years to develop. What is needed is the freedom to think and decide for ourselves. The government can say things but we shouldn’t have to.

The pledge may exist, but students should not be expected to recite it. Although the concept may seem far-fetched, it is possible for “freedom to” and “freedom from” to exist in tandem.