City councilor proposes program that would allow for an optional extra year of high school

Photo courtesy Creative Commons

Hoping to improve college retention and graduation rates among former Boston Public Schools students, City Councilor Michael Flaherty has proposed instituting an optional 13th year of school.

April 2, 2019

Hoping to improve college retention and graduation rates among former Boston Public Schools students, City Councilor Michael Flaherty has proposed instituting an optional 13th year of school.

“As we know, we live in a competitive global economy that requires our students to have efficient skills to access and fully participate in this economy – and as a result, we need to advocate for collective methods to close the achievement gap in our education system,” Flaherty said in a statement March 22.

Flaherty said he hopes to provide Boston’s students with another way to prepare for life after high school, whether they plan to pursue a traditional four-year college, vocational school or a community college by giving students the chance to stay at high school for one additional year to take college preparatory classes.

“Essentially, what I am presenting is to have a discussion on Year 13 so that we could have an additional resource to close the achievement gap,” Flaherty said.

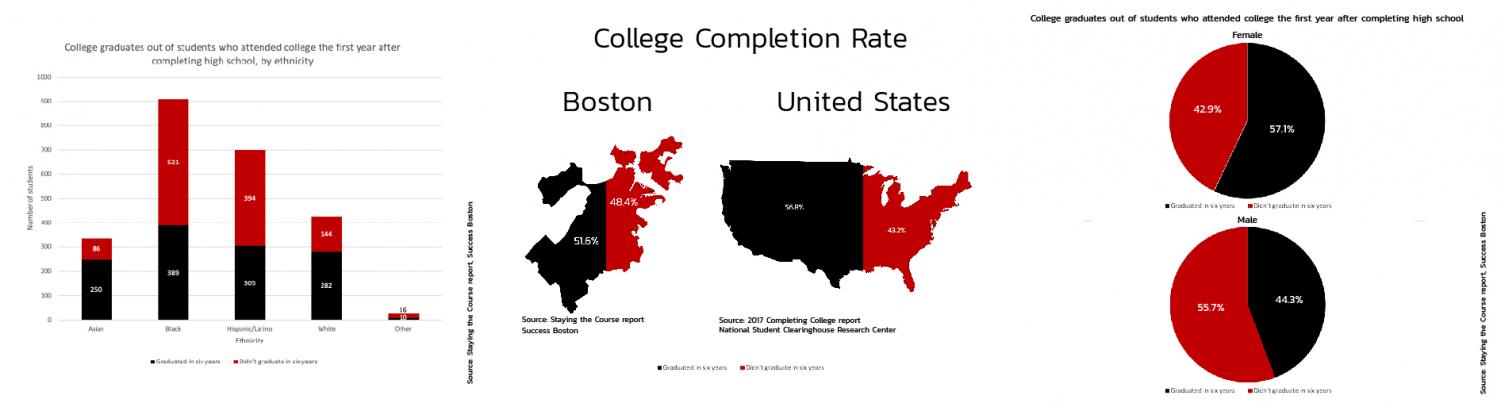

Currently, almost half of Boston’s high school graduates do not earn a college degree within six years of graduation, while even Boston’s best students struggle to earn degrees.

The Boston Globe’s Valedictorian Project revealed a handful of unsettling trends surrounding the outcomes of the Boston Public Schools’ high-achieving students. Over a quarter of Boston’s valedictorians who graduated between 2005-2007 did not attain a bachelor’s degree within six years of graduating high school, and roughly 40 percent of them make less than $50,000 per year.

Success Boston, a citywide college completion initiative, found that most male and minority students didn’t graduate college within six years after finishing high school.

The Globe cited financial turmoil and personal trauma as some reasons why valedictorians could not finish college, but some students interviewed in the report blamed BPS for their struggles in college and difficulty breaking into Boston’s lucrative tech sector.

If Flaherty is able to secure adequate funding and support for his proposal, Boston’s graduates could wind up finding more success in college: According to a 2007 study of students who had a one-year gap between high school graduation and college enrollment, students with the gap year were found to have 2.3 percent higher college GPAs. Additionally, low-achieving students were found to be more impacted by a gap year, a potentially valuable trend for some of Boston’s students struggling to adjust to college.

The study also noted the impact that a student’s motivation can have on their grades. Many colleges now encourage students to take a year off to regain their motivation and recharge following the stresses of high school and college applications. Middlebury College encourages all their accepted students to consider a gap year.

Greg Buckles, Middlebury’s dean of admissions, said its students who take a year off “hold a disproportionately high number of leadership positions on campus” and earn higher grades in a message to accepted students.

Elie Codron, a first-year international relations and economics combined major at Northeastern, spent his gap year taking rigorous classes in Israel and even with a packed schedule, he said his gap year helped him prepare for college.

“Whenever people ask me if I should take a gap year, [I say] it was a great decision,” Codron said. “It helped me become more mature, think about life differently and [gave me] a new outlook on life.”

Codron, who took classes from 7 a.m. to 11 p.m. some days, said his gap year gave him skills for both college and life after school. He said it gave him the chance to consider “the type of person I want to be” and gave him a great advantage when starting at Northeastern.

“Now that I’m in college, I know that I already have a plan for the future,” Cordron said.

Flaherty’s proposal would give students a similar chance to reevaluate their life goals while gaining additional skills to prepare themselves for college. A study conducted by Temple University and the American Gap Association found that 73 percent of students who had taken a year off felt better prepared for college. That same study also found that parents’ level of education is a large barrier to students who may hope to take a gap year, finding that 81 percent of gap-year students had parents who both had at least a bachelor’s degree.

In contrast, the United States Census found that just 35 percent of Americans over 25 have a bachelor’s degree or higher.

A separate study conducted by the Centre for Analysis of Youth Transitions, funded by the United Kingdom Department of Education, found that students who had taken gap years were more likely to be from families of higher socioeconomic status and more likely to be a native English speaker. About one third of BPS students are classified as English learners.

Given that taking a gap year seems to be a privilege mostly available for students coming from families with college degrees, Flaherty’s proposal could help close the achievement gap by opening up more options to students coming from families without any previous college graduates.

The main roadblock to Flaherty’s proposal will likely be funding. Flaherty’s 13th year proposal would be available to any graduating student of a Boston public high school, and since 71 percent of Boston’s class of 2017 planned on continuing their education, he could find his proposal too expensive to pass.

“The viability of this idea, like others that could be helpful to students, may hinge on whether the legislature takes action to fix the broken and inadequate funding levels for public education, particularly in urban school districts,” said Jessica Tang, president of the Boston Teachers Union in an official statement.