Activists conflict on prostitution policy

Cherie Jimenez joined other activists in advocating for the Nordic model at a summit held by the Coalition for the Abolition of Prostitution, or CAP International, in Mainz, Germany, earlier this month.

April 18, 2019

18-year-old Cherie Jimenez was in a rush to get married, but not completely by choice: There was a baby on the way. By the time she was 19 — her child only months old — her husband had become abusive.

At 21, gathering her courage and belongings, Jimenez decided to leave. Months later, though, the strain of single parenthood brought her back to square one, and she was out of options again.

When a friend suggested that she prostitute herself, the choice seemed like a second chance at freedom. It wasn’t. Jimenez didn’t break out of the system until she was in her late 30s.

Now, almost two decades later, Jimenez leads operations at the EVA (Education, Vision, Advocacy) Center, a program that has helped hundreds of women in their struggle to escape a cycle of poverty and prostitution. Since she founded the Center in 2006, Jimenez has repeatedly called for governments to introduce what some call the “Nordic model” of enforcement, which would shift liability away from the prostitutes and towards people soliciting or facilitating their services.

Last fall, her efforts and those of other activists appeared to make some headway. In November, Democratic Rep. Kay Khan introduced a bill to the Massachusetts State House that would remove legal penalties for prostitutes themselves, a key policy point of the Nordic model. While that bill and similar ones are unlikely to pass, its introduction suggests that legislators are beginning to shift their approach in the battle against prostitution.

Jimenez said that changing the way people think about prostitution — legislators and voters both — is essential to stopping it. Prostitutes are victims, not criminals, she said.

“You can have someone that started at 15, and now they’re 30, and they got caught in these systems. They might be looked upon, at 30 now, as complicit in their victimization,” Jimenez said. “Prostitution for a lot of people is just a continuum of violence that started probably early on, so you have layers and layers of this … harm, exploitation, violence, poverty, marginalization.”

For many — particularly uneducated women and members of ethnic minority groups — prostitution is easy to fall into not because it’s an attractive option, but because it’s the only option, economically speaking. Jimenez said that after being hit by a “perfect storm” of problems, she saw prostituting herself as a necessary step.

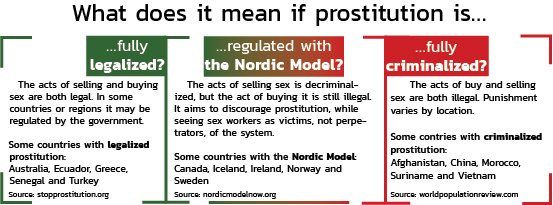

Many activists debate the pros and cons of the different methods of legal approach to prostitution.

“It doesn’t take a lot, when you’re kind of stuck, for someone to say, ‘Oh, I know what you can do,’ and introduce you into it,” she said. “You think you can make a considerable amount of money doing it, you’re kind of disconnected anyway. It’s a whole set of factors that make you think ‘Okay, I can do this.’”

Marie-Eve Sylvestre, a professor of civil law at the University of Ottawa, said for many people that find their way into sex work, the factors are similarly complicated.

“In some cases … it’s actually a choice,” she said, “It can be a choice based on constraints and the economic context … In some cases, it’s a choice along with different options of work that are also degrading.”

Research seems to support the fact that not everyone enters the system for the same reason. In India, for example, researchers found that women chose sex work because it gave them more freedom and autonomy over their bodies, higher earnings and a more flexible work schedule than other employment opportunities. A small study conducted in London in 1984 found that significant portions of prostitutes interviewed cited earning potential, opportunity for social interaction, independence and lack of employment as reasons for entering the industry.

Jimenez said once you make the decision to enter the industry, it’s incredibly difficult to leave. Prostitution is not a problem because prostitutes don’t want to stop; it’s a problem because prostitutes aren’t given the choice. According to a 1998 study, 92 percent of women in prostitution say they want to leave but can’t because of lack of money or food.

Other activists argue that the Nordic model, first adopted in 1999 by the Swedish government, made it more dangerous for women who choose to involve themselves in the system. Desmond Ravenstone, an activist who has worked for full decriminalization of sex work for over thirty years — once even running for president on a “sexual freedom” platform — said that sex workers are put in danger when clients are afraid of legal repercussion.

“For people who do sex work for survival and for sustenance, it makes them work harder and in more risky situations,” he said. “They will take clients who they otherwise would not take, because they’re desperate for money, and they will forgo very necessary screening processes to determine the potential risk that a client might pose.”

Sylvestre agreed with this sentiment, adding that sex workers under the Nordic model often start working in less-policed areas to increase their chances of successfully finding a client. She said this can put sex workers — particularly ones from marginalized populations, who she said work on the street more frequently — at even more risk of violence.

Ravenstone said that in some areas, end-demand legislation does not stop police officers from harassing sex workers. Instead, he said, it simply changes their methods of mediation. Ravenstone and Sylvestre said sex workers in some end-demand areas are rounded up by police and driven away from the places they work.

The difference in opinion between activists calling for full decriminalization and those pushing for the Nordic model is fundamental — and it is perfectly illustrated by a difference in terminology. Ravenstone considers sex work a legitimate profession: He and his allies see no harm in it as long as violence is not involved. Jimenez and those who share her beliefs would assert that prostitution — never “sex work” — is an inherently violent system.

“It’s just the fact that [you’re] using your body, using and selling part of your body,” Jimenez said. “We’re whole people. You cannot sell part of your body and remain whole … Just in that act, it is harmful.”

Jimenez said that when you look at the type of people the system exploits, the inherent injustice in the system is even more clear.

“Who is usually caught in these systems? It’s usually the most marginalized and poor women. Especially now, and I know because I’ve talked with hundreds coming through here. [It’s] the most vulnerable of women,” Jimenez said. “Who are the people purchasing sex? Usually people of entitlement, money, access.”

Jimenez said end-demand style bills like the one proposed in Massachusetts, which would usually be followed by programs that help people exit systems of sexual exploitation, are essential to ending the cycle of harm. Typically, she said, outside help goes a long way.

For Jimenez, that help came in the form of someone showing her how to apply to Another Course to College, an adult education program run by the University of Massachusetts. Jimenez said that while returning to school was difficult for her then, women who try to leave prostitution today often face even more obstacles than she did.

“It’s harder for young women, especially now, [with] everything that’s going on in our communities,” she said. “Finding a place to live, you can’t just go get an apartment. If you’re 18, and you’ve aged out of [The Department of Children and Families], where are you going?”

Jimenez added that as housing costs have increased, educational requirements for most jobs have expanded as well, and colleges have become less accessible.

Because no end-demand bills have passed in Massachusetts, Jimenez and her colleagues at the EVA Center — many of them also survivors of sexual exploitation — try to mitigate these problems themselves. As part of its exit program, the EVA Center offers a safe house for nine women and their children and allows survivors to rely on its “solidarity fund” as they work to find employment. Until lawmakers more seriously consider their argument, their hope is that they can continue to help people get out, just as someone helped Jimenez more than a decade ago.

While Sylvestre supports a full decriminalization model, she said that regardless of the legality of sex work, programs need to be put in place to offer resources to people trying to break out the industry.

“Whenever a woman is exploited, feels exploited, and doesn’t want to be in that position anymore, and [she’s] looking for help to do something else, then [we] should be supportive,” she said.