Column: Despite historic ‘Parasite’ Oscar win, the Academy remains biased against foreign films

February 25, 2020

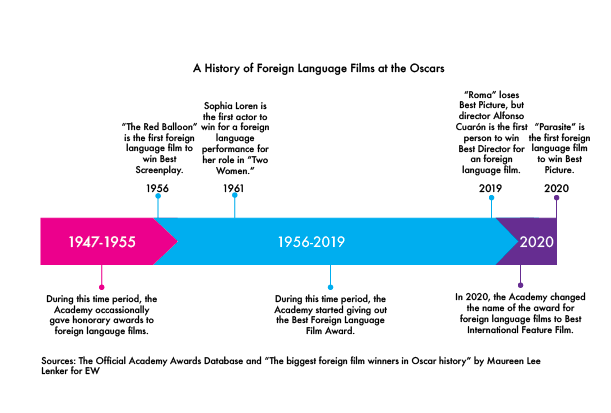

Bong Joon Ho’s cinematic masterpiece “Parasite” won Best Picture at the 92nd Academy Awards ceremony on Feb. 10, which marks the first movie not in the English language to win the coveted award. The film follows a poor family that plots to become employed by a wealthy family by posing as unrelated skilled workers.

Highly acclaimed by critics, “Parasite” presents a satirical social commentary on class inequality in South Korea. By the time the Oscars rolled around, it had already won the Palme d’Or — arguably the most prestigious award in the film industry — at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival, sweeping the competition in a unanimous vote.

The movie’s Best Picture win gave the Oscars fresh legitimacy. The Academy, the organization responsible for awarding Oscar nominations and trophies, has been dogged by allegations of sexism and racism in recent years. A foreign film winning the biggest award of the night is surely a sign of progress.

However, the fact that it took this long for a non-English language film to snag Best Picture shows that there is still a long way to go before the Oscars, and Hollywood as a whole, becomes truly inclusive of foreign film industries.

The cards were stacked against “Parasite” from the beginning. The movie is almost entirely in Korean, and in general, Americans don’t like reading subtitles. From a commercial standpoint, it is unusual that it got the level of support it did from domestic movie-goers. Furthermore, the Academy is made up of mostly Americans working in the American film industry.

The Academy members seemingly have had an implicit bias against foreign movies for years. In the 92 years of the Academy Awards’ existence, only 12 non-English language films have ever been nominated for Best Picture.

Instead, foreign movies are often relegated to the Best International Feature Film category. While the category gives important, much-needed recognition to movies made outside of the United States, there are still systematic problems with the way nominations are chosen and how the category itself is viewed by the Academy.

One of the criteria for Best International Feature Film nominations is that the movie should primarily be in a non-English language. However, due to Britain’s colonial past, usage of the English language is widespread in many countries. Nigeria’s very first submission to the Best International Feature Film category, Lionheart, was disqualified from Oscars consideration this year because the film is primarily in English.

The entire situation, in addition to essentially barring Nigeria and similar countries from ever competing in the category again, showcases how the Academy retains archaic views on what the word “international” means.

Shawn Shimpach, associate professor of communications at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, sums this notion up succinctly. “The Academy seems to have inherited a sort of a 19th-century colonial mindset, in that there is a center in which they imagine themselves — Hollywood — and then there’s a periphery, where they imagine other industries,” he said in a phone interview with Vox. “They have inherited these 19th-century categories of how you identify these differences. The one they have chosen is language — cultural difference signified through linguistic difference.”

The category also suffers from a systematic problem. The very existence of a separate category for international films makes it hard for foreign movies to garner other, more prominent nominations like Best Picture. It seems likely that the Academy has not given some foreign films Best Picture nominations because they were already nominated for Best International Feature Film. One notable example of this is the Mexican film “Roma,” which was a frontrunner for Best Picture at last year’s Oscars, but fell short to Peter Farrelly’s “Green Book.” This might partially explain why non-English language movies are rarely nominated for Best Picture, even if those same movies sweep prestigious non-American awards like the Palme d’Or.

One could argue that since the Academy is headquartered in the United States, the American film industry should be the primary focus. However, the Academy should reflect on its role as a prominent institution with global recognition and decide how they are going to recognize exceptional filmmaking — regardless of where it occurred.

“The Oscars are not an international film festival. They’re very local,” said Bong.

He’s right. But he doesn’t have to be.