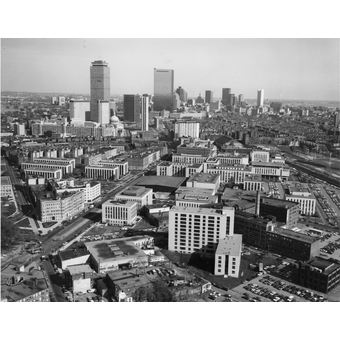

In 2023, the United States Supreme Court struck down affirmative action in college admissions, fueling feelings of frustration and isolation in Black students at Northeastern. Though Northeastern is still reckoning with a 35% drop in Black student enrollment seen in the Class of 2028, the university made notable leaps in the late 1960s to appeal to Black students, The Huntington News found through a review of archives from Asa S. Knowles’ presidency.

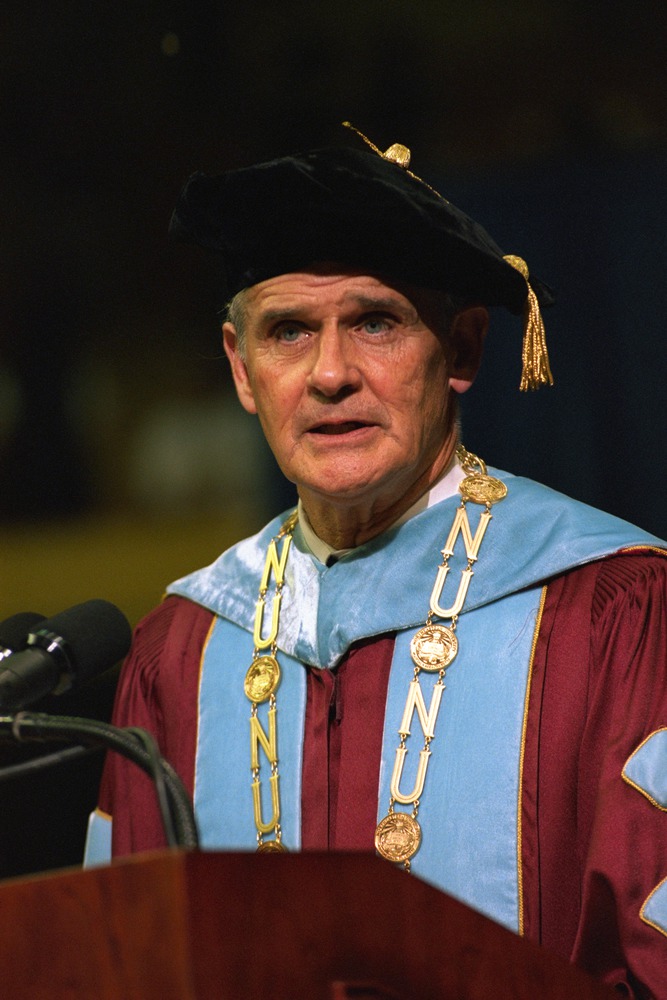

Knowles, Northeastern’s third president from 1959 to 1975, encouraged Black students to advocate for changes at the university that would benefit them and Northeastern’s educational mission. During his tenure, Knowles oversaw the implementation of a Black studies program at Northeastern, the establishment of the African American Institute and an increase in Black student enrollment.

Northeastern’s John D. O’Bryant African American Institute was established in 1969 after a little over a year of deliberation between Knowles, faculty and Northeastern’s Black Community Concerns Committee, according to documents in Northeastern’s archives. The organization was initially titled the Afro-American Institute and was renamed in 1993 in honor of John D. O’Bryant, Northeastern’s vice president of student affairs from 1979 to 1992. O’Bryant was also the first Black president of the Boston School Committee and served from 1977 to 1990.

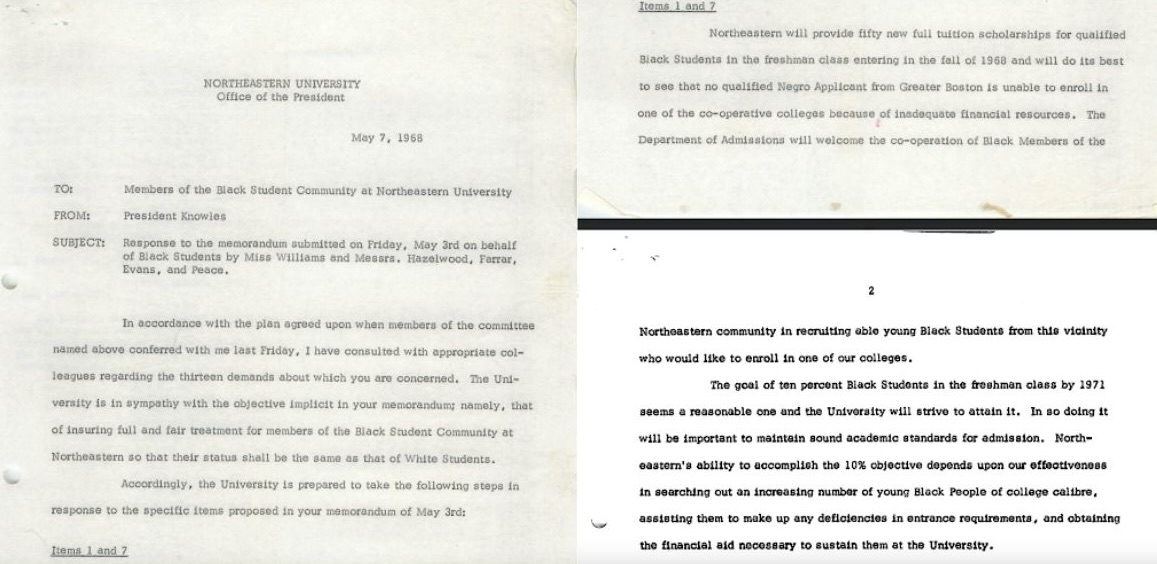

“Northeastern will provide fifty new full tuition scholarships for qualified Black students in the freshman class entering in the fall of 1968 and will do its best to see that no qualified Negro applicant from Greater Boston is unable to enroll in one of the co-operative colleges because of inadequate financial resources,” Knowles wrote in a May 7, 1968 letter to “Members of the Black Student Community at Northeastern University.”

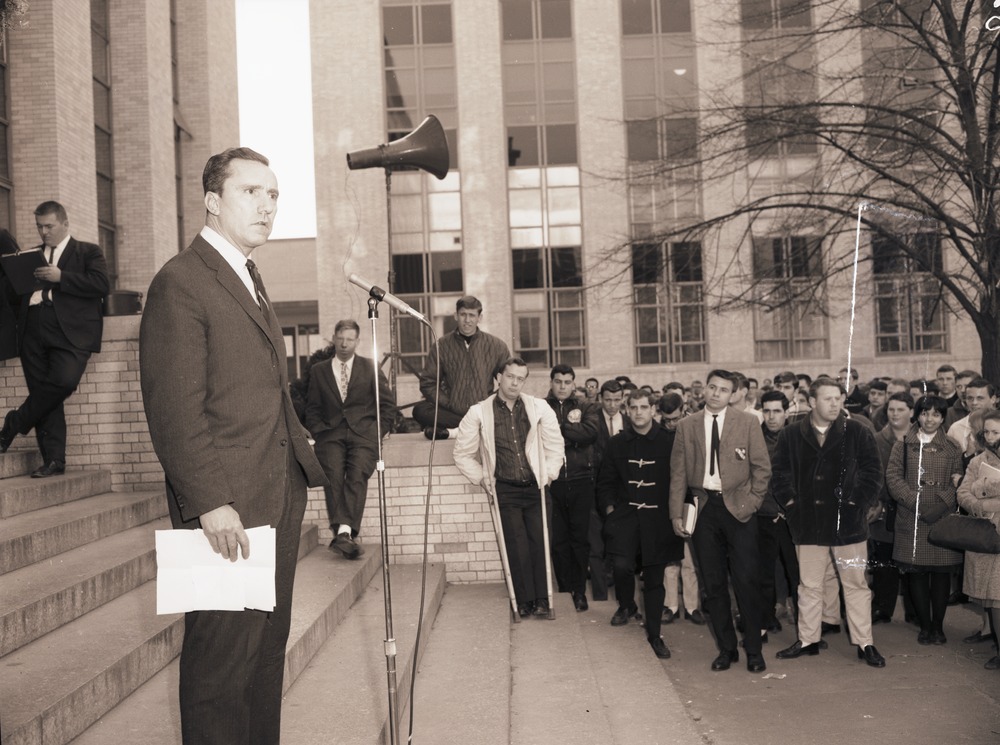

The letter came in response to a list of 13 demands made four days prior by Black students. One demand called for the formation of the Committee on Black Community Concerns — a committee of faculty, administrators and African American students that would ensure the university upheld its commitments to the Black community. Another demand included a goal to increase Black student enrollment to at least 10% of the incoming freshman class by 1971.

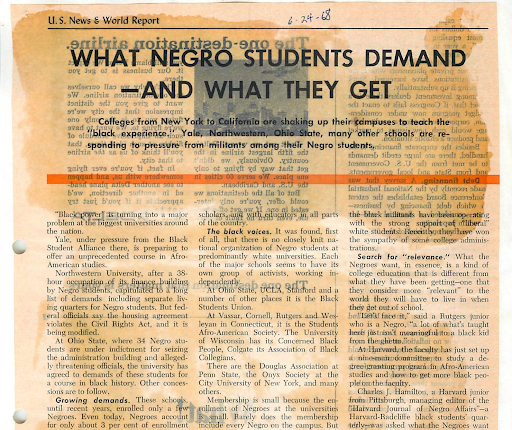

The 13 demands proposed by Black students were designed to ensure full and fair treatment of Black students at Northeastern and encourage success after their graduation. During this time, many Black student groups at other universities were also submitting demands to improve opportunities for Black people in higher education, invigorated by the ongoing Civil Rights Movement.

By 1968, the Civil Rights Movement had sparked the creation of national legislation that greatly improved racial equality. Two such pieces of legislation were the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, sex or national origin and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which made voting easier for people of color in the South by undoing Jim Crow laws. However, following Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination April 4, 1968, conflicts intensified and the movement saw a reinvigorated push, particularly on college campuses. University of San Francisco was the first to implement an African American studies program in 1968.

At Northeastern, Knowles was adamant about achieving his goal of bolstering Black student enrollment.

“The goal of ten percent of Black students in the freshman class by 1971 seems a reasonable one and the University will strive to attain it,” Knowles wrote in his letter.

But today, only 5.1% of Northeastern’s 2028 graduating class identify as Black — half of the target goal set for the freshman class 53 years ago.

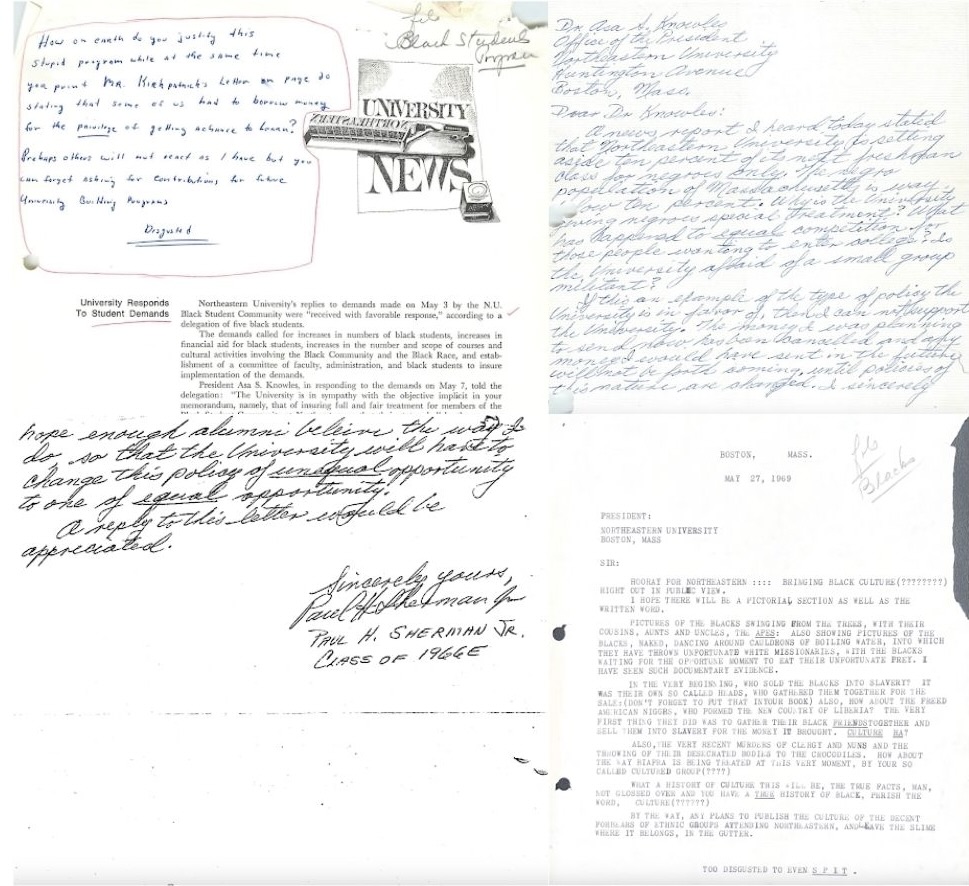

In the late 1960s, Knowles’ aspirations to increase Black student enrollment did not bode well with many in Northeastern’s community, The News found.

“Why is the University giving negroes special treatment? What has happened to equal treatment for the people wanting to enter college? Is the University afraid of a small group [of] militants?” Northeastern alumni Paul H. Sherman, a 1966 graduate, wrote in a letter to Knowles. “If this is an example of the type of policy the University is in favor of, then I can not support the University. The money I was planning to send now has been canceled.”

Several other letters made their way to Knowles’ desk, some using racial slurs and provocative language.

“I sincerely hope enough alumni believe the way I do, so that the University will have to change this policy of unequal opportunity to one of equal opportunity,” Sherman wrote.

Sherman’s sentiment was echoed 55 years later by the Supreme Court decision to remove affirmative action. The majority decision, delivered by Chief Justice John Roberts, established that colleges can no longer consider race when admitting students, saying universities’ admissions have wrongly deduced that “the touchstone of an individual’s identity is not challenges bested, skills built or lessons learned but the color of their skin.”

Despite facing public scrutiny at the time, Knowles defended the university’s decision to prioritize Black student enrollment.

“Northeastern is located on the edge of Roxbury next to the ghetto area and it cannot ignore the problems of this area,” Knowles wrote in a May 10, 1968 letter addressed to Sherman. “Two of the great problems are for better education and for equal opportunities for Negroes. The University’s relationships with its Negro students have been very friendly and the students have been very appreciative of any programs we conduct to help the community.”

Northeastern kept reports tracking Black students’ academic performance in order to most effectively support their success. A 1968 report compiled by John A. Curry, then the director of admissions who would later become president in 1989, tracked 80 Black high school graduates who enrolled in a special summer tutorial program. The report showed that 35% of the 80 students were in “academic difficulty” as defined by a quality point average — average quality points earned per credit hour — of 1.4 or lower.

“This author prefers the point of view that 65% of the 80 students, a large number of whom otherwise would not have attended college are functioning at a better than failing level,” Curry wrote in the report.

Given the backlash from some people on campus, Black students who began to make a home at Northeastern had a few wishes for how to make their community feel more welcome.

On Feb. 14, 1969, the Black Student Committee submitted a proposal for the establishment of an “Afro-American Cultural Center and a Black Studies Department which would offer courses leading to a major and degree in Black studies.”

After several months of deliberation between the Black Student Committee and Northeastern’s Faculty Senate, an agreement was reached to establish a noncredit Black studies program in which the Black Student Steering Committee would have full control over course material, staff and operation of the Institute.

“Black perspectives and accomplishments have not been given their rightful place in American education,” Northeastern’s Faculty Senate wrote in a letter to the Black Student Committee. “The University’s best interest, and that of the wider society is served by cooperation with you.”

On March 7, 1969, Northeastern’s Board of Trustees approved the use of the Forsyth Annex Building for an Afro-American Cultural Center. The African American Institute was later moved to what is now John D. O’Bryant, adjacent to West Village F. The Forsyth Annex is currently used for the Latinx Student Cultural Center.

In their official proposal to the university on May 20, 1969, the Black Student Committee wrote the following explanation detailing the importance of Black studies:

Black Americans have incurred many injustices at the hands of white society. They are far too numerous to list here, but one that stands out from the rest is the systematic and ruthless elimination of all materials related and relevant to black people in both public and private, so-called educational institutions.

Black perspective and accomplishments have all but been excluded from American textbooks.

What is the role of the University in this “Crisis in Black and White?” All we ask of the University is that it do its job. It must educate whites as well as blacks (blacks foremost however) in course matter that should have been a normal part of the University curriculum for the past 300 years.

Dr. Morris Abram, president of Brandeis University, recently stated that “It is not the job of the University to cure all the ills that society has inflicted upon black people.” Perhaps not, but as one pensive student later responded, “If it is not the job of the University to heal the wound at least it should be able to soothe the pain.”

Northeastern University did not create the racial pit that engulfs the nation, per se, but in not establishing a curriculum in “Black Studies” it would sub-consciously partake in its perpetuation, as it has unwillingly done for the past 60 or so years of its existence.

Knowles and Northeastern staff agreed.

“In their planning for the proposed Institute, the Black student community group members conducted themselves in an exemplary manner,” Knowles said in a May 30, 1969 memo to university staff. “They have followed and are continuing to follow all the proper channels to accomplish their goals.”

The Black Student Committee was able to accomplish a majority of their goals with cooperation from Northeastern staff, but as the decline in Black student enrollment for the Class of 2028 demonstrates, the fight for racial equality in higher education is far from over.

“The diversity of students plays a big role in how people of color feel belonging on campus,” Shania Rimpel, a fourth-year biology major, told The News in October. “It’s important to show students of color that there is a space where they can find each other and so it makes the transition easier.”