In letters penned over a century ago, Northeastern’s first president warned colleagues of the threat a future leader with too much power could pose to the university.

During his tenure as president from 1898 to 1940, Frank Palmer Speare — also Speare Hall’s namesake — restructured Northeastern’s administration and founded the law school in 1922. But the university’s survival after he stepped down from the top position was at the forefront of his mind, The News found through a review of his letters in Northeastern’s archives.

“If one of our men should become bull-headed, domineering, dictatorial, unreasonable, hot-headed and animated by sledge hammer methods,” Speare wrote in a 1923 letter to Galen D. Light, who served as the secretary of Northeastern at the time, “this man could do irreparable damage as he would be quick-tempered, obstinate, brazen, outspoken and undiplomatic.”

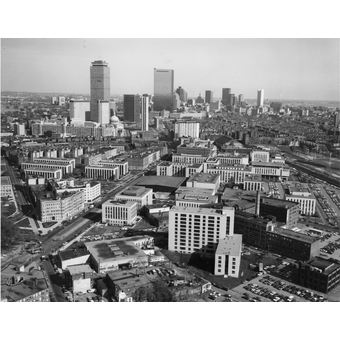

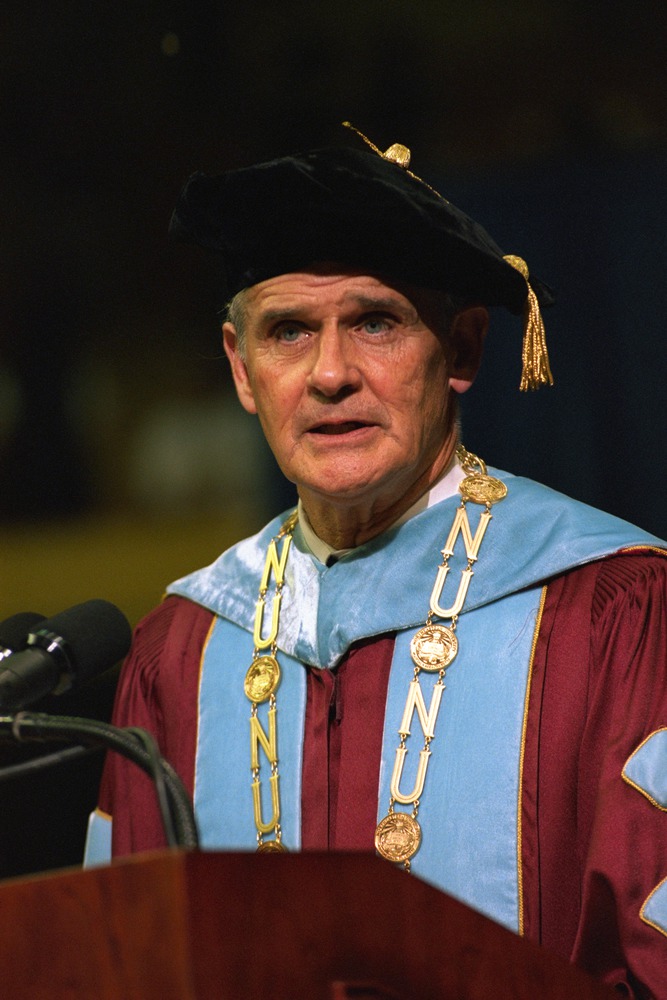

Today, Northeastern — which has operated under the leadership of President Joseph E. Aoun for nearly 18 years — manages 13 campuses across Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom. It’s undeniably a powerhouse — boasting state-of-the-art research centers and a renowned co-op program that drew 98,373 students to apply for the fall 2024 semester.

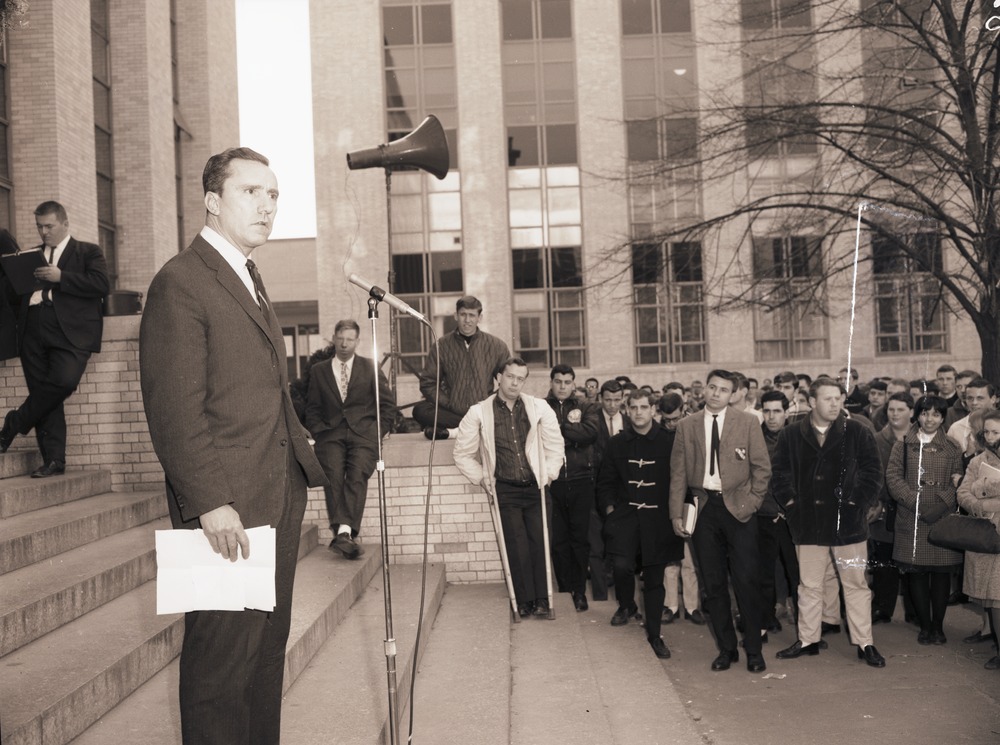

Despite its booming success now, Northeastern had humble beginnings. When it was founded in 1898, the university was called the “Evening Institute for Younger Men” and hosted night classes in the YMCA of Greater Boston on Huntington Avenue. As a commuter college, Northeastern was an outlier among its peer academic institutions in Boston like Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which were older and more traditional.

To establish Northeastern as an influential university, Speare led a significant reorganization of Northeastern’s administration by simplifying its leadership model. He reshaped the existing nine administrative units into three and appointed one director to each unit. Speare envisioned the three unit directors would lead the university and report to the president, according to his 1923 letter.

The second part of Speare’s plan involved reducing how much unit directors were paid. Prior to the new plan, there were two directors: Ira Flinner, headmaster of Huntington School, an all-male preparatory college that also operated out of the YMCA, and Carl Ell, head of the engineering unit, who became the university’s second president in 1940. The men’s great successes were reflected by their high salaries, which were “largely disproportionate to the others and in fact dangerously prohibitive,” Speare wrote in 1923. His new plan would distribute money more equally among the three unit directors.

Speare was proud and protective over his new plan, which he methodically outlined in the 1923 letter to Light.

“I am of the opinion now that the present form of contract will have a wonderfully beneficial effect upon our entire organization and will enable us to keep our costs at the minimum and claim the maximum of service with the lowest possible financial risk or burden to be assumed by the directors of the Association or others,” Speare wrote.

Speare also recognized the dangers associated with the reorganization and outlined in extensive detail all of the ways in which it could possibly go wrong. Speare even requested that Light return the letter after he read it so Speare could “file it in the archives for future reference as bearing upon conditions which may or may not arise as a result of the signing of the contracts.”

Speare’s main concern was that the ambition of the inexperienced directors would impede their ability to efficiently run the university together. Although Speare would continue as Northeastern’s president for another 17 years after the reorganization in 1923, his fears about new leadership ran deep.

Speare detailed the weaknesses of Ell and Flinner, his directors, and the possible dangers they could pose as leaders.

“Another individual is apt to be secretive, very dictatorial, super-sensitive, worries over detail, is thoroughly honest, right-intentioned and as much hurt by criticism or reproof as a spoiled child,” he wrote. “Any of these tendencies might become overdeveloped and lead to trouble.”

Speare explained to Light how the former administration was set up in a way in which he was able to either “mold the men into a harmonious whole” or “remove [them] wholly” from the position they occupied.

But with Speare’s proposed plan, this power-checking would become “more difficult,” he explained.

“It can be readily seen, therefore, that this group must be handled with the utmost care, must be watched, counselled, guided, encouraged, checked, stimulated, soothed, and kept very busy in order to preserve harmony,” he wrote.

Speare told Light that he would “stand by [the directors] and with them just so long as they are right.”

“Should they take the wrong turn of the road, however, and undertake to do things which I do not stand for, I shall assert myself to the utmost and openly oppose their propositions,” he continued. “The perfect harmony which has reigned here for the past twenty-nine years can be continued if the men are animated by the same objectives which have led me, but self-seeking, egotism, bad temper, intolerance, bigotry and selfishness can never enter in and the good work go on as heretofore.”

With that, Speare concluded his letter, which The News found in the Snell Library archives over 100 years later: