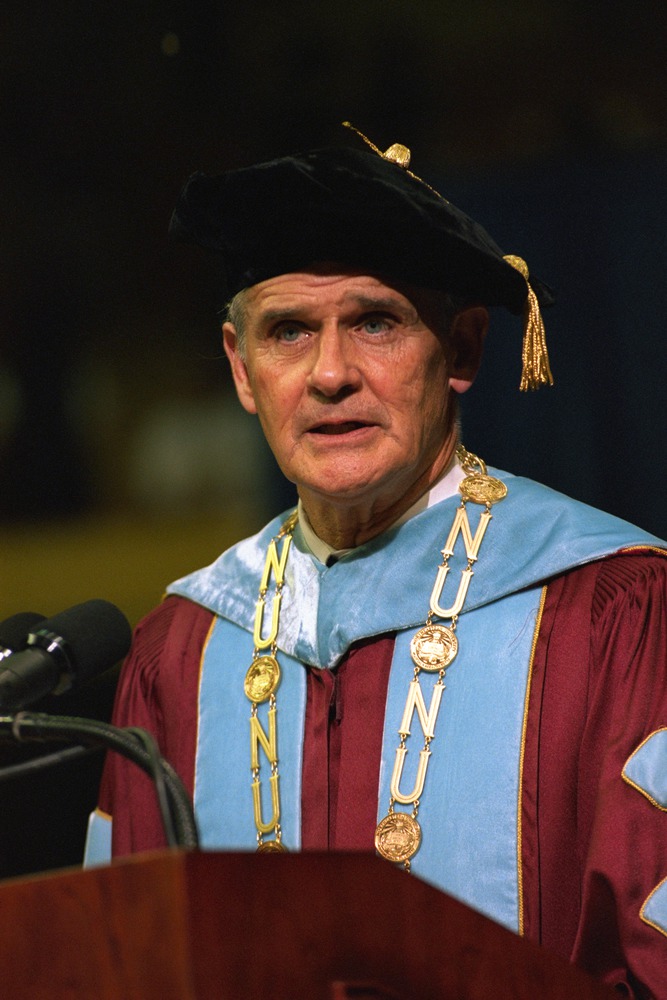

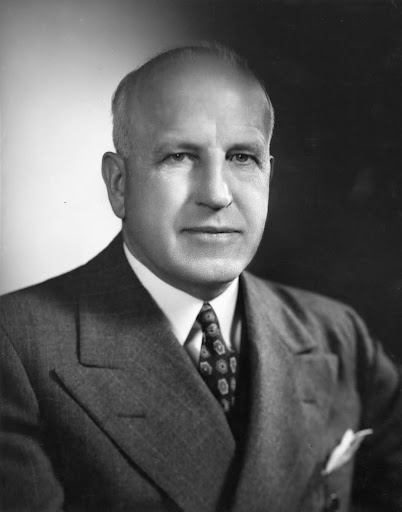

Every Northeastern student who has walked through Krentzman Quad has passed Ell Hall. Yet, few know the story of the man it honors: Carl Stephen Ell, Northeastern’s second president, who transformed Northeastern from a small, YMCA-affiliated institution into a global university pioneering cooperative education.

Ell served as the president of Northeastern from 1940 to 1959. Known as “Mr. Northeastern,” his long career began in 1910 when he joined the university as a civil engineering professor. At the time, the university was operating out of the local Young Men’s Christian Association, or YMCA, according to a biography in the Northeastern Archives collection.

While studying for his bachelor’s and Master of Science degrees at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, or MIT, Ell taught his first daytime civil engineering class at the YMCA Co-operative School of Engineers, which eventually became Northeastern University, as one of seven faculty members. He conducted a class with eight students in the attic of the building, where students frequently banged their heads on the ceiling because it was so low, according to the transcript of a speech dictated by Ell in 1958.

“In those days, we just simply had no land, no equipment and no money,” he once told a group of alumni, according to his 1981 obituary in The Boston Globe, which described him as “the president who built Northeastern.” “But we did have one great asset, we had ourselves.”

Ell quickly climbed the leadership ladder at Northeastern. After two years of teaching classes, he became the head of the Department of Civil Engineering in 1912. Then, in 1914, he became the assistant dean of the School of Engineering, and in 1917, he was appointed dean of the College of Engineering. As dean, he spearheaded organizing and developing Northeastern’s engineering program and helped establish the evening engineering program, according to a memo from the Northeastern University Public Relations Office in 1949.

“Northeastern,” Ell said, according to the Globe’s obituary, “is a new type of college or university. It is one designed specifically to meet the needs of that large group of young men who have ability and ambition but are limited to financial resources.”

Early life

Born in Staunton, Indiana, on Nov. 14, 1887, Ell was the son of Jacob and Alice Ell. He received a Bachelor of Arts from DePauw University in 1909. Ell then moved to Massachusetts to receive his Bachelor of Science from MIT in 1911 and his Master of Science in civil engineering from MIT in 1912. He married Etta May Kinnear on June 10, 1913. Together, they had one daughter.

Ell received his Master of Education from Harvard University in 1932. Throughout his life, Ell was awarded five honorary degrees, including from Boston University and Emerson College.

“I’m just a farmer from Indiana,” Ell told Northeastern News, now The Huntington News, in 1958, near the end of his presidency. “A kid from the crossroads who wanted to learn and is having a lot of fun doing it.”

Building Northeastern

Ell’s presidency was marked by a dedication to making higher education accessible to everyone. He believed that someone’s character and work ethic should determine their success, not their race, class or family.

As a kid who grew up on a small farm in Indiana, Ell understood the struggle of balancing working while attending college. He believed Northeastern should help bridge the gap between the lower-middle class and higher education. This belief guided his leadership through his many roles at Northeastern, and he oversaw impressive university growth throughout his tenure.

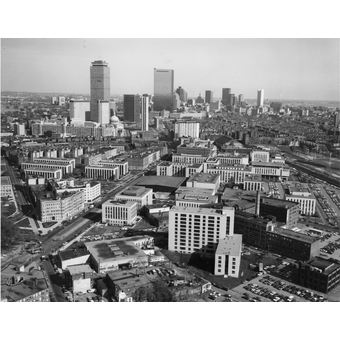

Appointed the university’s president July 1, 1940, Ell grew Northeastern’s assets from $2 million to $30 million during his term and added 19 buildings to Northeastern’s campus.

Though construction was halted during World War II, Ell continued actively raising money for the day it could resume. Following the war, the “Student Center building was erected in 1947, followed by the Library Building, the Godfrey Lowell Cabot Physical Education Center, Hayden Hall [and] the Graduate Center,” according to a 1958 article in the Boston Globe Magazine.

Student enrollment increased from 5,000 to 18,000 during Ell’s tenure, the most significant increase since the university opened in 1898. Ell was also responsible for the creation of three colleges at Northeastern: the College of Business Administration in 1922, now called the D’Amore-McKim School of Business; the College of Liberal Arts in 1935, now the College of Social Sciences and Humanities and the College of Education in 1953 whose programs now primarily exist in the College of Professional Studies.

In 1943, Ell greenlit the enrollment of female students to compensate for the men enlisted in the military during World War II.

Before becoming president, Ell served as vice president from 1925 to 1940. He played an integral role in Northeastern’s first land purchase during this time. On Aug. 20, 1929, Northeastern purchased an acre of land behind the YMCA for $126,092.90. The coal trestle and cinder dump referred to as “no man’s acre” was the first in a string of land purchases that would lead to Northeastern’s expansion across Huntington Avenue.

Advocate for the co-op program

Ell believed in the value of students combining practical experience with the theory they learned in their college classrooms.

“The cooperative idea is the correlation, in the most effective way, of college training and practical experience in business and industry,” he wrote in a statement about Northeastern’s co-op engineering program, initially printed in the School and Society journal in 1927.

Ell explained how Northeastern’s co-op program reflects the American value “that a man should be evaluated for what he is and what he can accomplish, rather than who he is and where he came from — socially, racially or economically. In keeping with that tradition, all capable men and women should be given the opportunity to prove themselves and develop their capacities to the utmost.”

Establishing traditions

Perhaps Ell’s most beloved contribution to Northeastern was his installation of the husky as Northeastern’s mascot in 1927.

During the 1926-27 school year, when Ell was vice president of the university, student demand for a mascot increased significantly as more Northeastern athletic teams were established. In a speech Ell delivered in 1958, he recalled how students wanted the university to “adopt a dog — any dog — which would make its home here around the University and invade corridors and classrooms occasionally.”

Unfamiliar with the idea of a mascot, Ell was confused by the idea that “some homeless dog” would come live at Northeastern as the mascot, he said in the same speech. Despite his skepticism, he figured if Northeastern was going to have a mascot, it should have a “good one” that reflected the “qualities found in Northeastern students.”

In February 1927, Leonhard Seppala, a famous dog sled driver from Alaska, was in Poland Spring, Maine, for a dog sled race competition with his 12 Siberian huskies. Ell was inspired by the opportunity to bring home a “real sturdy, dependable, working dog” as Northeastern’s mascot. After making an appointment with Seppala, he traveled to Maine to visit, where he took his first dog sled ride. He discovered that the husky was the perfect mascot to represent Northeastern. For the price of $100, he purchased a husky.

On March 4, 1927, Seppala brought the chosen dog to Boston, where they were met by a parade of students eager to welcome the newest member of the Northeastern community at North Station. Led by the Northeastern band, the parade took Seppala and the husky “through Scollay Square, up Boylston Street and Huntington Avenue where the Husky was presented Northeastern and inaugurated as King.”

“This original King Husky I was found to be the most unusual animal,” Ell said during the 1958 speech. “He always appeared to be the monarch of all he surveyed — beautiful, dignified and striking; very friendly in his attitude towards men, but afraid when women came near and rather wild when he took to the open.”

Today, a golden statue of King Husky I stands in Ell Hall. Northeastern students often rub its nose for good luck.

Beloved by the community

Ell’s accomplishments speak volumes, but the quality of his character spoke louder, according to those who worked with him. In a special edition of the Northeastern News celebrating Ell’s career at Northeastern following his retirement announcement, faculty members said Ell was the epitome of a true leader.

William White, who was a Northeastern vice president during Ell’s presidency, said “[Ell] symbolizes the very essence of Northeastern University and its Co-operative Plan; the deep-rooted conviction that our American democracy will succeed only if higher education is truly open to all regardless of race, creed or financial limitations.”

“He has the great quality as an administrator of giving something today and then telling you, ‘Do it your own way,’” said Harold Melvin, dean emeritus of Northeastern who retired in 1957. “This is the mark of an outstanding leader — faith in those who work with him.”

“He’s never too busy for us,” said Marjorie Prout, who served as the administrative secretary of the Office of the President during his presidency and after his retirement.

Leadership during turbulent times

World War II raged during Ell’s tenure as president. On Jan. 1, 1945, the Globe reported that Ell “urge[d] education for an enduring peace” to combat conflict among Americans.

“After this war, education programs must be such that students who graduate from our scientific and technical school will be able to participate intelligently in an effort to create enduring peace in a democratic social order,” he told the Globe. “Man should use the products of science for constructive and not destructive ends in that democratic social order.”

Commitment to making higher education accessible

As the Boston Sunday Globe described April 19, 1981, Ell was dedicated to making higher education accessible to everyone.

“The only way we can have a democracy is to educate the maximum number of people,” he said. “How nice would it be, in theory, to run a school on the basis of training only the top percent? Where would our society go then? You’ve got to think about the other 90%.”

As of the last decade, 52% of Northeastern University’s student body come from families with incomes in the top 10% nationwide, according to New York Times research and data from Opportunity Insights, The News previously reported. Additionally, 7% of the student population come from families among the top 1% of earners.

Ell also had strong opinions on universities receiving subsidies following the war.

“Northeastern University believes that [a] federal subsidy for higher education should be a last resort,” he said Nov. 6, 1945, during his annual speech to the university corporation at the Omni Parker House. “Northeastern also believes colleges and universities have no right to make demands upon the public for gifts or tax-supported appropriations unless every effort is first made to use their educational plants to the fullest capacity and, where feasible, for day and evening classes.”

Today, Northeastern utilizes several federal grants to assist its students financially with tuition costs. The university offers grants, including the Federal Pell Grant, Federal Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grant and Massachusetts State Grant, to eligible undergraduate students with financial needs. Additionally, Northeastern offers federal loans to graduate students through the Federal Direct Graduate PLUS Loan.

A legacy of dedication

Ell’s dedication to and love for the Northeastern community was unparalleled, documents and memos reviewed by The News show.

Ell spoke to student reporters about his love for his job in an issue of the Northeastern News published Jan. 31, 1958, commemorating his retirement.

“I don’t want to stop working,” Ell said. “We have developed a great institution — well-organized, well-manned, with a splendid curriculum and with students who want to get ahead. I want to make it possible for them to get ahead.”

Ell explained how he found joy even in the challenges he faced as president.

“The plan of combining theory and practice has always been a great challenge. I’ve had fun doing it,” he said. “Everything has come naturally to me. I’m no genius, but I do things as they seem right to me.”

Furthermore, his dedication to Northeastern prevailed over the more lucrative job opportunities he was offered.

As the Boston Globe Magazine reported Oct. 19, 1958, Ell decided to take a job at Northeastern when “the country was still in the firm grip of the Great Depression and Northeastern had no land, no buildings or reputation. Vice Pres. Ell was offered the presidency of a large, prosperous and well-known university in the Midwest. Fortunately for Northeastern, he turned down that offer.”

Retirement

Ell retired in 1959 and transitioned to a role as a chancellor at Northeastern’s Boston campus. In 1981, he died at 93 after 70 years of devoted service to Northeastern University.

Two years before his retirement, he addressed the Northeastern University Corporation in a 1957 speech, where he remarked on the mission he saw for the university: giving students from all walks of life an education.

“The great advances of our time have not been brought about by mediocre men and women but by distinctly superior men and women,” he said in the speech preserved in Northeastern’s archives. “Northeastern, therefore, has before it the opportunity and the challenge to help young people from the middle class to discover and to develop their talents to become uncommon men and women, and to make, each in his own way, a contribution to human progress.”