Over the past several decades, Northeastern has expanded its empire by buying up smaller universities around the country and accepting students into alternate admissions programs such as Global Scholars and N.U.in. But the elite institution — where a mere 5.2% of applicants accepted to the Boston campus in fall 2024 — was much more inclusive several decades ago, Northeastern alumni say.

“Northeastern [was] a working class, working man’s university. That term was around [but] I don’t think they’d ever dare use that word,” said Paul Cioto, 70, who was a student at Northeastern from 1972 to 1977.

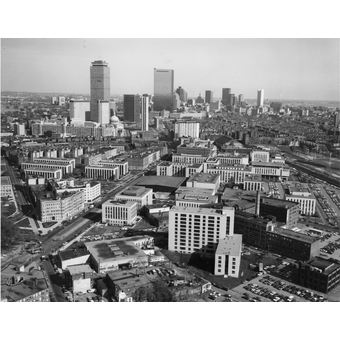

Cioto was one of five alumni who spoke with The Huntington News and attended Northeastern when it was a commuter school, with parking lots scattered around campus for students to use. As the institution worked to establish itself, parking lots were turned into buildings, residence halls and state-of-the-art research centers for the university.

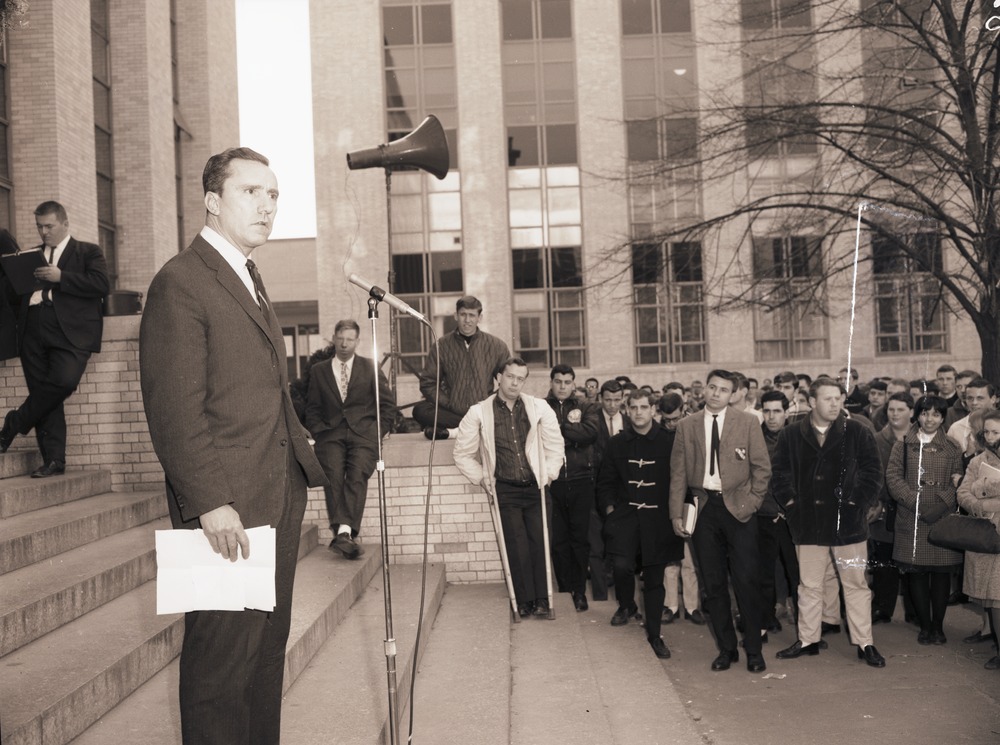

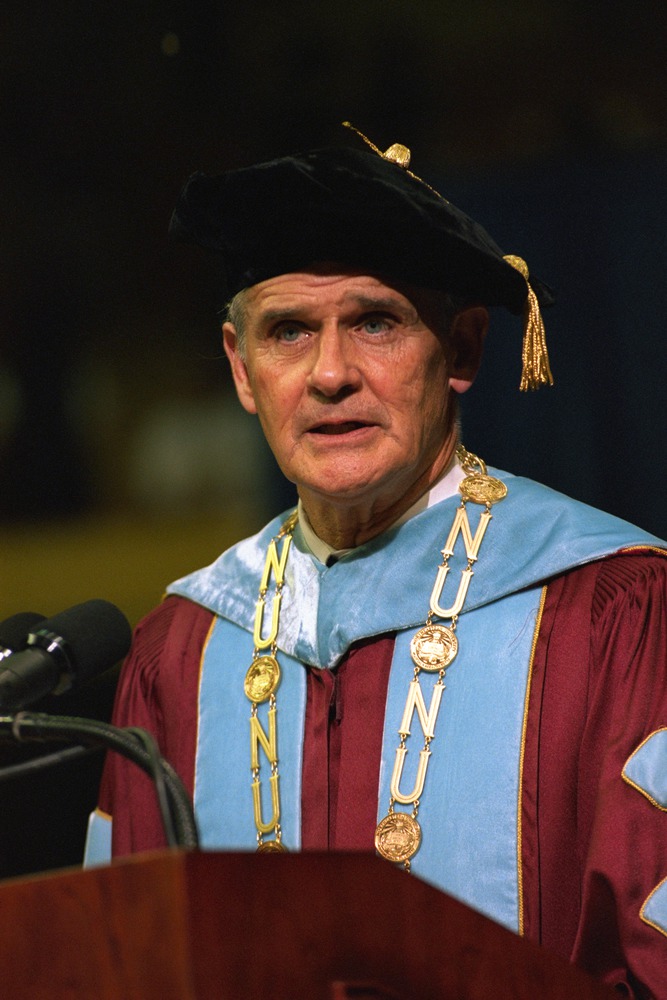

William Fowler attended Northeastern as a student from 1962 to 1967 before becoming a distinguished professor emeritus of history in 1971, eventually retiring in 2017.

“When Northeastern was founded by the YMCA, its mission was to provide education for young men. Then World War II comes along, they’re short of men, so they admit women,” Fowler told The News. “And whether by intent or not, it aimed at a certain social economic class of people. First, young men, then young men and women.”

Today, Northeastern has expanded to cover 73 acres of land in Boston with more than 19,000 undergraduate students.

While the Boston campus itself has grown, some alumni said the admissions process has become much more competitive.

“Northeastern was bigger than it is today,” said Dan Kennedy, who graduated in 1979 and now teaches journalism in the College of Arts, Media and Design. “It was the largest private university in the country. One of the ways that they move toward their current model of onward and upward is that they shrunk. They became more selective. There aren’t as many students here as there were back in the ‘70s.”

Kennedy recalled how Northeastern was seen as an attainable university for those who wanted to get a college education without financial stress.

“We were all first gen[eration],” he said. “Northeastern, at that time, was an alternative to a public university. The public universities like [University of Massachusetts] were in pretty bad shape at that time, meanwhile Northeastern offered an outstanding education and the tuition was quite low, and housing costs were quite low and they were not terribly selective.”

The commuter aspect of the school appealed to many students, especially those from the Northeast.

“Northeastern was predominantly a destination school for New England, New York and New Jersey … It was never on the radar of [West Coast] students,” said Susan Conover, who graduated from Northeastern with her bachelor’s degree in criminal justice in 1997, her first master’s degree in 1998 and her second master’s degree in 2003. She now works as an administrative coordinator in the College of Arts, Media and Design.

The socioeconomic class of students coming to campus shifted dramatically when the administration changed its focus to attract a different demographic, alumni said.

“What’s really changed is that there were always some students who really shouldn’t be here and they’re not here now,” Kennedy said of the university’s increase in academic rigor. “They were put in a position where they had a hard time succeeding and a lot of them didn’t get their degrees and now that type of student tends to not get admitted in the first place.”

With its increased selectiveness, Northeastern’s acceptance rate has plummeted, reaching an all-time low of 5.2% of students accepted to the Boston campus for the Class of 2028.

The increase in Northeastern’s prestige brought more international students to campus as well. Today, Northeastern has over 20,000 international students, the second most of any university in the country in the 2022-23 academic year.

“It’s become much, much more diverse in terms of geography — much more international,” Fowler said. “The students are much, much more diverse. When I was there as a student, we’re pretty much all men and women, white, African American [and] working class.”

Matt Carroll, who studied at Northeastern from 1973 to 1979 and then returned to the university as a journalism professor in 2016, said the main difference he sees in students now is the time spent on technology.

“Obviously, students have phones now. So every spare second, they’re on their phone or whatever. But I think students then are kind of like students now,” Carroll said.

Throughout Northeastern’s history, the co-op program continues to be what sets the institution apart from its competitors.

“I got a very fine education, wonderful teachers, but it was co-op that really had a monumental effect on my life,” Fowler said. Cicoto agreed that the program is “still the main attraction Northeastern has to offer.”

Today, the co-op program allows students to access full-time work opportunities across the globe. However, the jobs used to be New England-based, and students would hold them for 10 weeks, or one of their quarters, Cioto said.

“Most of my friends had co-op jobs in New England, not necessarily around Boston,” said Cioto, who completed his co-op experiences at Brockton Enterprise and The Boston Globe.

Fowler was one of the few students from the 1970s who went to Washington D.C. for his co-op, working for the National Archives.

“I went to Washington and I was unusual,” Fowler said. “Well, that wasn’t unusual when I was a faculty member talking to students. They were going everywhere.”

Northeastern used to feel like a smaller bubble than it is today, alumni said, with students rarely traversing beyond Ruggles Station or Matthews Arena.

“It was sort of an island in the middle of the city, and speaking of myself and my fellow students, we had very little contact with the city,” Fowler said. “We drove, parked in the gravel parking lot, went to classes, then went home, so we didn’t move about the city.”

As masses of students began to travel from across the country to attend Northeastern, they found it harder to live on campus with limited housing and began searching elsewhere, most notably in Mission Hill, Carroll said. This angered many of the locals who had lived there for generations, he said.

“It was always this tension with people living in the neighborhood,” Carroll said. “Northeastern driving up rents [and] they keep buying up residential buildings and turning them into this, that and the other thing. It’s an issue now and it’s always been.”

All five alumni said they have noticed the remarkable transition of Northeastern’s aspirations over time.

“After I graduated and [was] reading the alumni magazine, it just seemed like Northeastern just developed this obsession with improving its ranking in the U.S. News and World Report list of the best colleges in the country,” Cioto said. “They were almost obsessed with improving their image as a high class academic, upscale institution.”