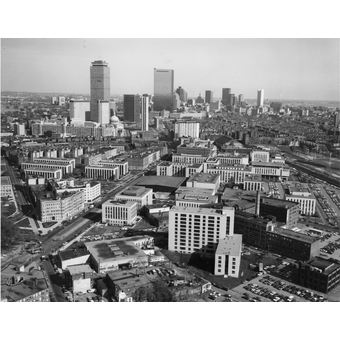

When the world is burning, people look to influential institutions to offer words of advice and reassurance. As Northeastern has grown from a commuter trade school to an international education network over the past 127 years, the seven presidents who have guided the university since its establishment have found it necessary to comment on pivotal world events, The Huntington News found through a review of archives.

Most recently, President Joseph E. Aoun and other top university officials have released statements regarding the wars in Ukraine and Gaza. But 83 years ago, the university’s statements on war looked very different.

Northeastern in World War II

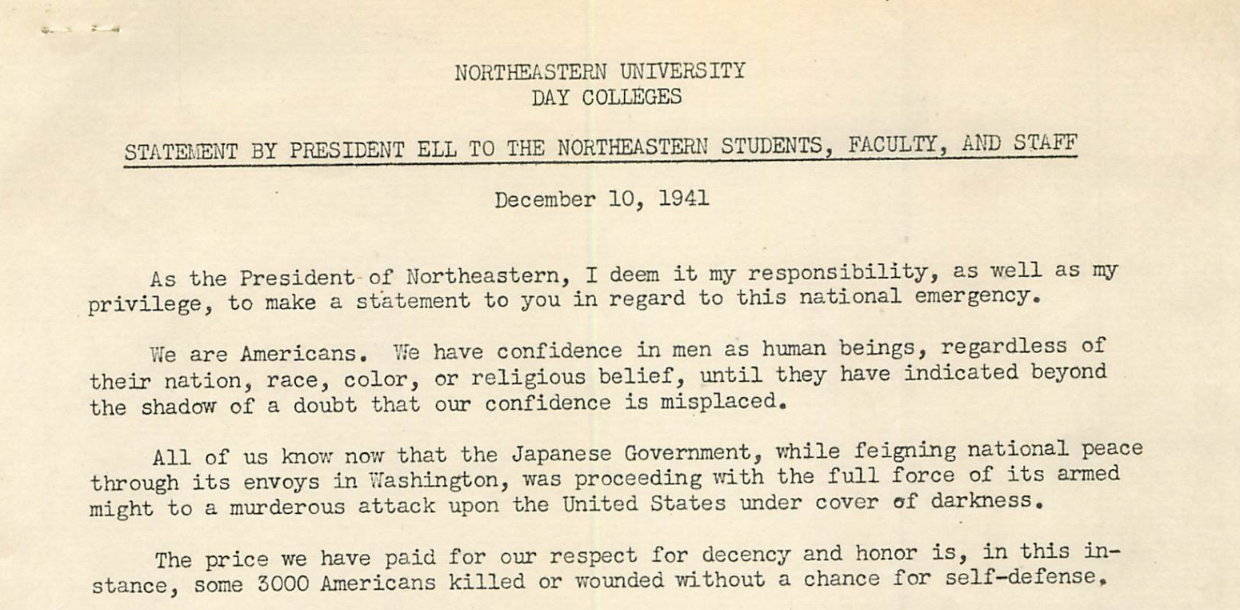

On Dec. 10, 1941, three days after the Imperial Japanese Army attacked Pearl Harbor, Northeastern President Carl Ell released a statement to students, faculty and staff.

“We have confidence in men as human beings, regardless of their nation, race, color or religious belief, until they have indicated beyond the shadow of a doubt that our confidence is misplaced,” Ell wrote, going on to say that Japan’s government betrayed that confidence.

More than 3,500 people were killed or injured in the attack on Pearl Harbor, including 2,335 service members and 68 civilians, and another 1,178 were wounded, according to the U.S. Department of Defense. The next day, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt asked Congress to approve his declaration of war, and the same day, the United States declared war on Japan.

Americans were preparing for a war on two fronts. The Germans declared war on the United States Dec. 11, 1941, the day after Ell’s statement to the university community.

“The idea that a president of a university would put out a statement is a little different than, say, thinking about Russia invading Ukraine,” said Laurel Leff, a retired professor of journalism and affiliate in Jewish Studies at Northeastern.

Leff has written several books about American history and journalism during the Holocaust.

“Every single man attending Northeastern University faced the fact that they were probably going to be sent overseas, whether it was to the Pacific or European theatre, so the idea that the president would feel obligated to say something and acknowledge this moment, I think, is different than anything that has happened before or since,” she said.

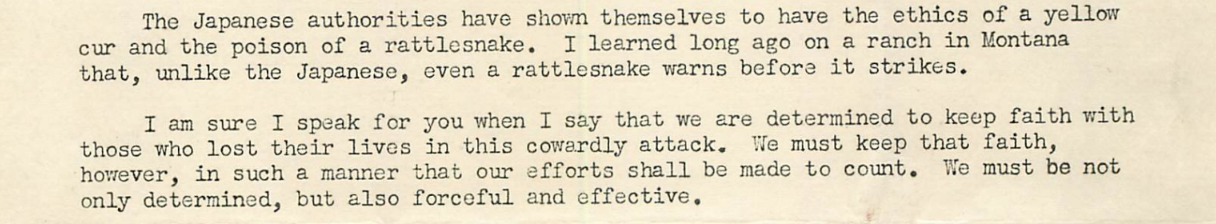

Further in his statement, Ell criticized the Japanese people, using language that academics today recognize as racist.

“There’s a horrible racist comment,” Leff said. “It’s not at all surprising — one of the interesting contrasts in the American press coverage of what was happening in Europe versus what was happening in Japan is that the racist part of our anti-Japanese sentiment was very front and center even in mainstream newspapers.”

Though Ell’s sentiment initially seemed to be addressed toward the Japanese government, his comparison to a rattlesnake lacks any such distinction: “I learned long ago on a ranch in Montana that, unlike the Japanese, even a rattlesnake warns before it strikes.”

As publications across the country spread the news in the days following the attack, some, like the Chicago Tribune and Los Angeles Times, refer to the Japanese as “Japs” on their front page, a term that is today recognized as a slur. Though the war was being fought on two fronts, racial undertones dominated coverage of the Pacific Theater.

“The Germans were quite horrible, but they’re not seen as horrible in racist terms,” Leff said, explaining that more Americans are of German descent than any other nationality. “They attacked us, which also probably colored things somewhat, but there is this underlying racism which makes us view the two theaters of operation somewhat differently.”

Upon Roosevelt’s issuance of Executive Order 9066, over 117,000 first- and second-generation Japanese Americans were forcibly relocated and placed into concentration camps across the United States. Thousands of people lost their homes and businesses because of “failure to pay taxes.”

“It is easier to kill your enemy if you portray them as not like you,” Leff said. “Asians who didn’t have emotions during Vietnam or crazed Jihadists after 9/11.”

With servicemen fighting overseas in Europe and Asia, Northeastern began admitting women in 1943. Thirty-three women enrolled in 1943, and in the next few years, Northeastern instituted an accelerated program that resulted in several graduating classes of 1944 and 1945.

In the years leading up to World War II, Northeastern opened a Civilian War Training Program, which allowed groups of reserve military students to complete their college educations before moving on to national service.

Earlier that year, in January 1941, the university started an engineering Defense Training Program “designed to meet the shortage of engineers with specialized training in fields essential to the national defense,” according to a page from Northeastern’s veterans library.

By 1943, Northeastern was authorized and funded by the United States War Department, now the Department of Defense, to expand the program into the Engineering, Science and Management War Training Program.

By the end of the war, more than 5,000 Northeastern students fought in the war and more than 200 died as the university moved to support national defense.

In the years after the war, Northeastern sought a more formal and permanent relationship with the Department of Defense and applied to form both U.S. Air Force and U.S. Army ROTC units on campus. The department initially turned down the application, but it was ultimately accepted and formed by 1951, attracting more than 800 students that year and quickly becoming the largest ROTC program nationwide with more than 2,800 cadets.

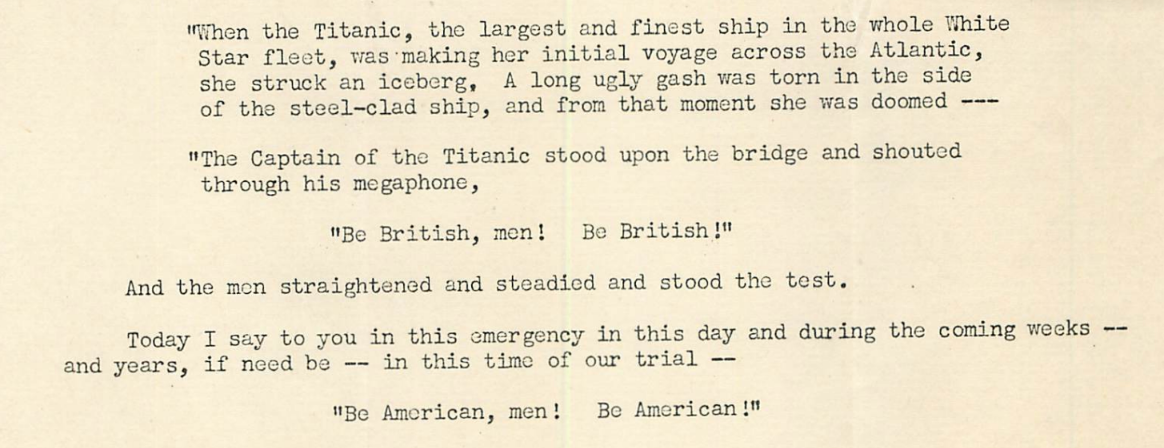

In his statement, Ell recalls the crew of the Titanic, who manned their stations after their captain shouted, “Be British, men! Be British,” now calling on Northeastern men, “In this time of our trial – Be American, men! Be American!”

“I think part of that is coming from the British stiff upper lip,” Leff said. “Still, the comparison to the Titanic is a little bizarre, but that just may be because the Titanic doesn’t loom as large in my life experience as it did obviously for President Ell.”

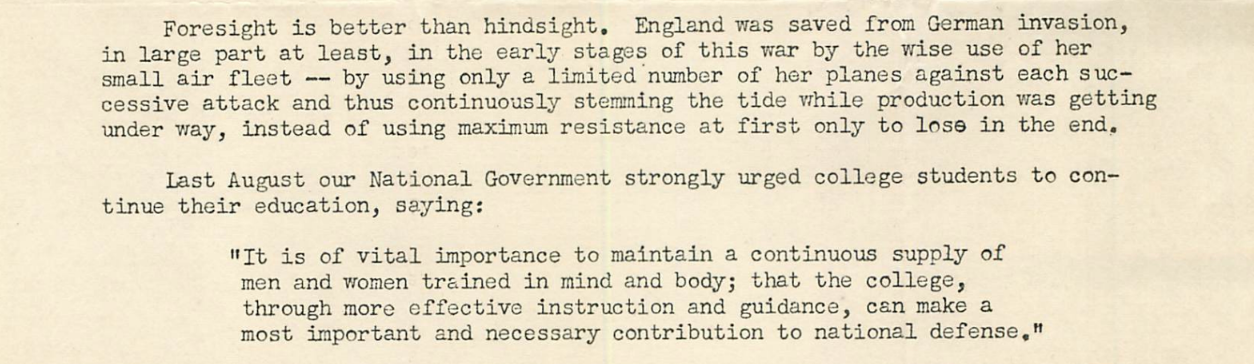

At that point German Luftwaffe were bombing England across the country, including in metropolitan areas like London and Coventry. German bombers killed 43,500 civilians over nine months of bombings.

“Now we know we won, we know we were able to gear up our production and produce Navy destroyers relatively quickly,” Leff said. “But at that moment in December 1941, it probably felt like we could lose, and so the idea that even if you are losing or sinking like the Titanic, you still need to stand strong, and where you would feel that most strongly in 1941 would be from the British and the whole British experience of the last two years.”

Northeastern in Vietnam

In 1968, Northeastern’s student body leaned more conservative, with the university’s focus on professional education rather than liberal arts studies. At the time, the university also had the largest voluntary ROTC chapter in the country. This meant Northeastern students were slower to participate in protests for the anti-war movement compared to other Boston schools.

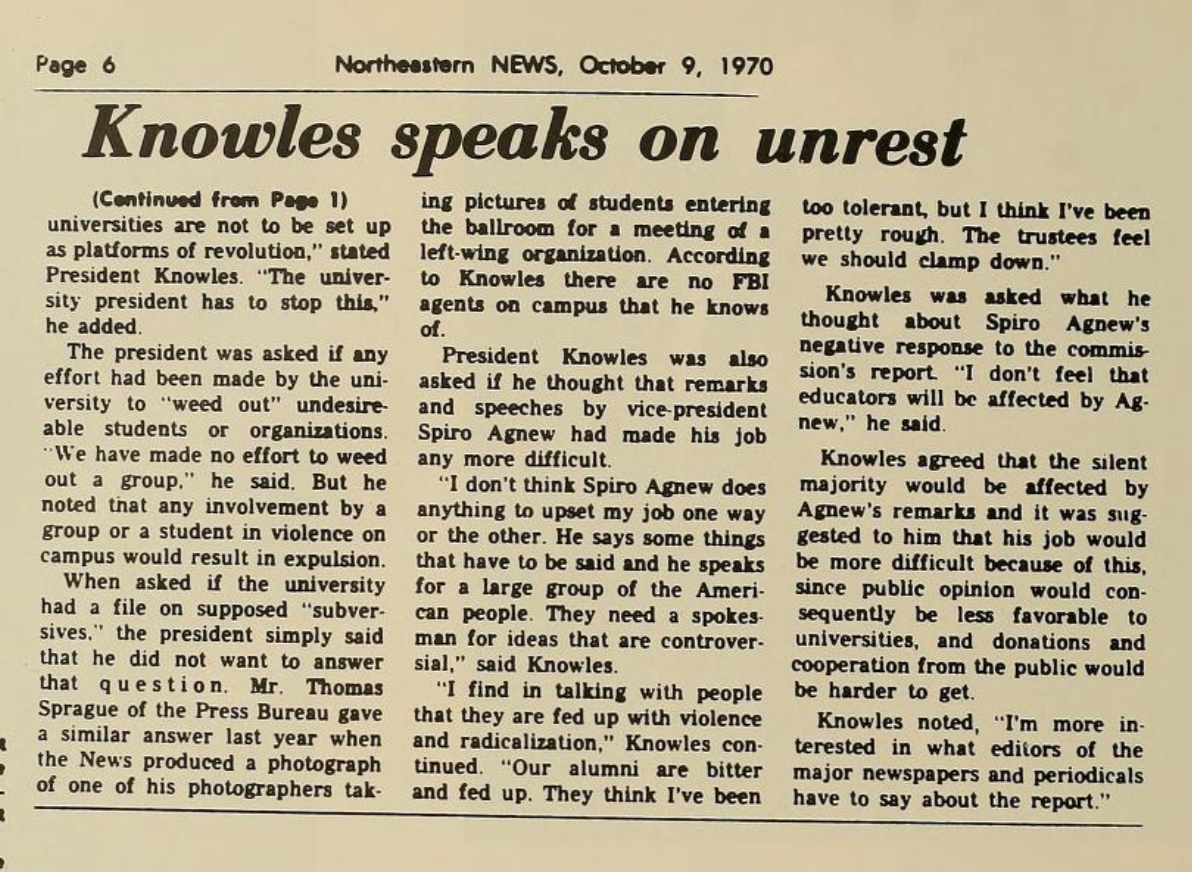

As the events of the Vietnam War were unfolding and public sentiment about the war was reaching a boiling point, Northeastern administrators were grappling with how to handle the escalating student protests on campus.

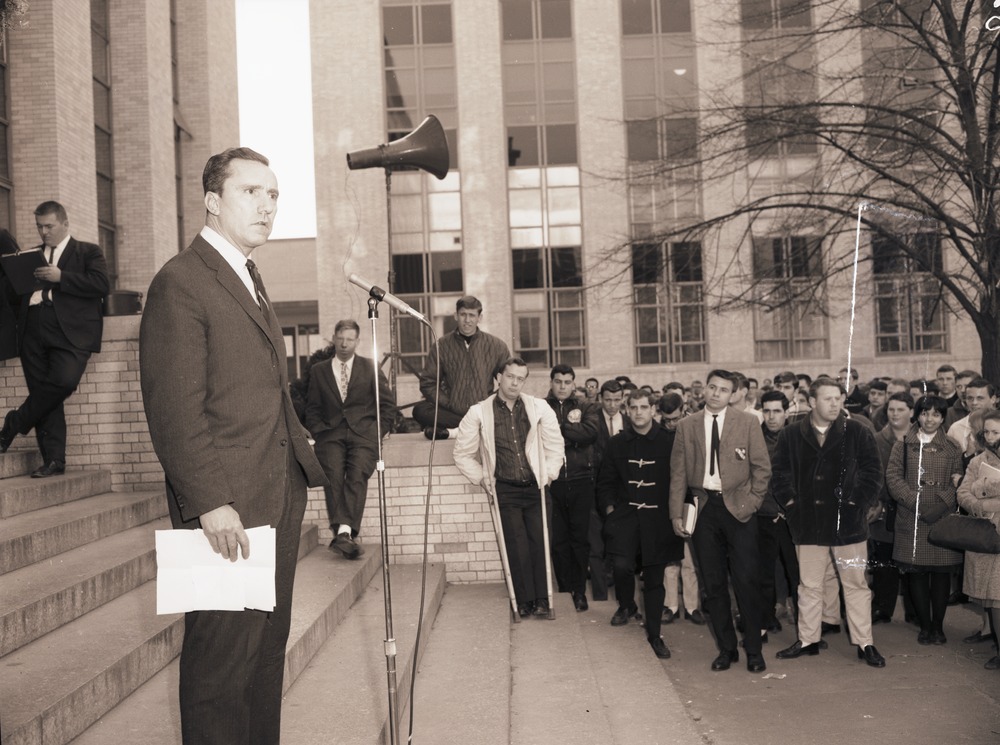

There were a few documented protests leading up to 1968; the first protest on campus in December 1965, when The Northeastern News, now The Huntington News, sponsored an event in support of the war. Around 2,000 students attended, many from the Young Republicans, and about 15 anti-war protesters picketed the event, according to Northeastern’s Library.

In the following years, Northeastern’s Students for Democratic Society, or SDS, chapter became more active, targeting the ROTC program and defense recruiters, including Dow Chemical Corporation, the manufacturers of napalm.

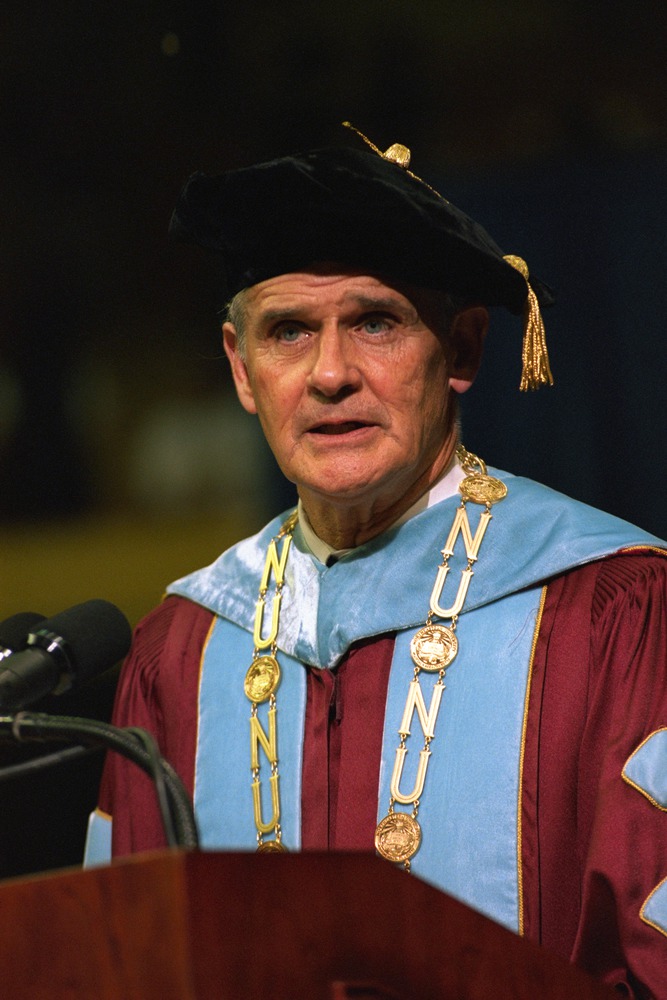

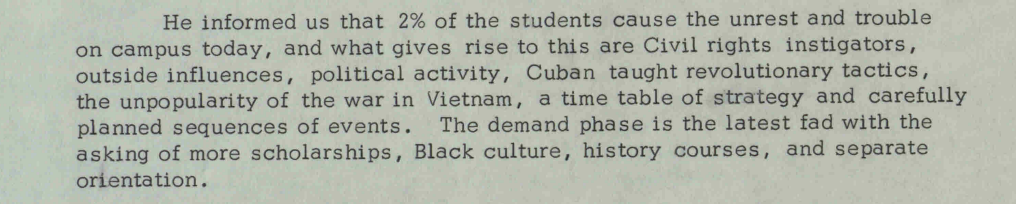

According to NU Faculty Wives Meeting notes from October 1968, President Asa Knowles addressed the current issues at the university, attributing unrest to “Civil rights instigators, outside influences, political activity, Cuban taught revolutionary tactics [and] the unpopularity of the war in Vietnam.”

In March 1969, both Northeastern’s President’s Advisory Council and the Student Council voted in favor of ending academic credit for the 11 ROTC courses offered after Harvard University’s faculty voted to do the same a month earlier.

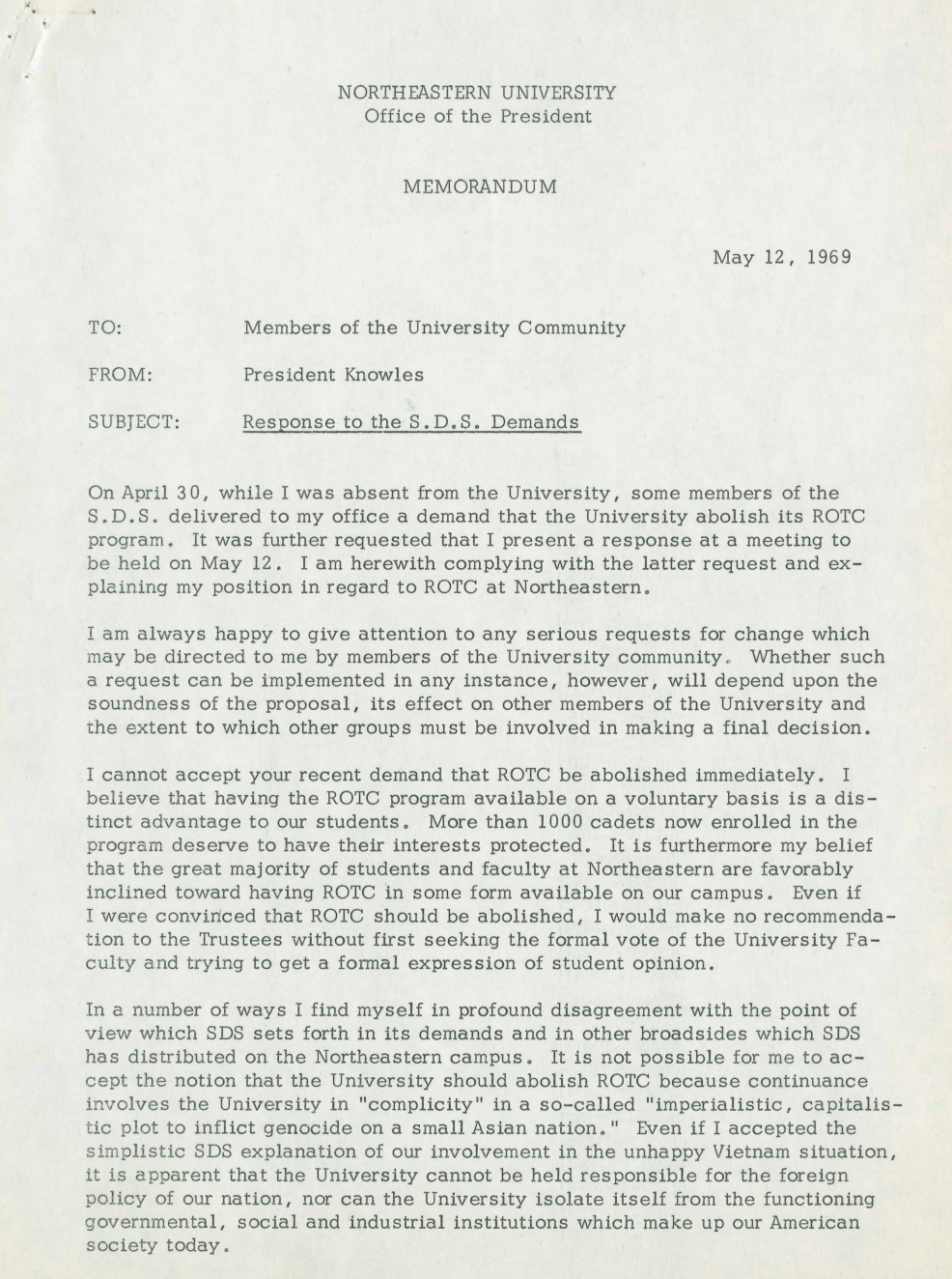

In May 1969, the SDS sent a letter to Knowles, demanding that the university terminate its ROTC for moral opposition to the war and its causes, as well as questioning the ability of the university to be impartial as an academic institution.

Knowles issued a response to the SDS’s demands, addressing the members of the Northeastern community: “It is not possible for me to accept the notion that the University should abolish the ROTC because the continuance involves the University in ‘complicity’ in a so-called ‘imperialistic, capitalistic plot to inflict genocide on a small Asian nation.’”

He continues, speaking to his personal belief in the “Citizen-Soldier” and contributing to the military establishment. He also explained that the same justification could call for the termination of engineering, physics and business administration studies or to deny students co-op opportunities perceived to be contributing to the “corrupt establishment.”

Knowles ends the letter noting that he would pass along the decision to the Board of Trustees if he were persuaded that these were the sentiments of the majority of the student body and faculty and would impose no presidential veto.

The Interfraternity Council conducted a referendum vote on whether the ROTC should remain at Northeastern, and though only about 39% of full-time students were represented in the results due to co-op, about 19% of students voted to abolish ROTC on campus. With these results, Knowles formed an ad hoc committee of students, faculty and staff to re-evaluate ROTC’s standing, which voted 9-1 against abolishing the campus’ ROTC chapter.

Students also pressed the university to ban General Electric from campus, arguing the company’s ongoing national labor dispute was tied to the war. Though they demonstrated at a recruitment event, the administration again refused to meet their demands. Students and protesters clashed with police during spring demonstrations, as campuses across the U.S. reached a boiling point amid Vietnam War protests.

After President Richard Nixon announced the U.S. invasion of Cambodia, protests flared up, and on May 4, 1970, the Ohio National Guard shot and killed four unarmed students at Kent State University.

Around 100 colleges and universities filed official plans to strike with the newly-opened National Strike Information Center at Brandeis University, which estimates that this movement of protests and strikes took place at 883 schools and involved more than 1 million students. Northeastern students voted 4,619 to 1,529 in favor of boycotting classes. In the early morning of May 11, an anti-war protest on Hemenway Street ended in over 100 riot police swinging clubs and injuring at least 20 people, with some even reporting police smashing property and breaking into dormitories and other residential spaces to attack people at random.

Days later, students said Knowles had told the press that normal activities had resumed on campus and asserted that he was spreading misinformation and harming their efforts, though the strike would officially end two days later as students started to leave for the summer.

That summer, Knowles released his annual report, which asserted that Northeastern’s public image suffered from “faculty members, who support radical students, especially those who take over facilities and destroy property.”

The Northeastern News continued to allege the administration was trying to drown out student voices and shut down their publications, but following a series of critical articles in September 1971, Knowles assembled a Student Publications Committee to “create policies and procedures which will assist our student publications in serving the best interests of the entire University community.”

After clashing with student groups and protesters for years, however, the president’s tone was notably different in his address to the graduating class of 1971.

Somewhat unsurprised by this turnaround, Leff said, “During the Vietnam era with some exceptions, the student sentiment, and certainly by the time you get to 1971, was fairly consistent and fairly anti-war.”

Despite many years of a robust ROTC program, its enrollment dwindled.

In the fall of 1970, only 110 of Northeastern’s incoming 3,196 first-years joined ROTC, and more than a year after its formation, the ROTC Committee released a report recommending a reduction in curriculum hours and discussions with the army to remove weapons and drills from campus.

Northeastern at present

In the past several years, Aoun has issued statements on the wars in Ukraine and Gaza, as well as on domestic unrest during the 2020 Black Lives Matter movement.

“The catastrophic destruction and loss of life inflicted by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine unites us all in sadness and shock. War, violence, and displacement anywhere are affronts to humans everywhere,” Aoun’s statement on the war in Ukraine reads. “In the true spirit of Northeastern, our community is also taking action. The Ukrainian Cultural Club has brought together people from across our University to protest the war. Students are lending tangible support through fundraising. Faculty members are casting light on the geopolitical situation and have contributed valuable research, as can be seen on this website.”

Aoun’s statement clearly indicated that he stood firmly in support of Ukraine.

“Our university’s mission is shaped by reason, fairness, and the pursuit of knowledge for the benefit of all humankind. These principles exist in stark contrast to authoritarianism, suppression, and brute violence,” he wrote. “As we join in support of Ukraine, let us be guided by our highest ideals of freedom and enlightenment.”

Days after the Oct. 7, 2023 attack the next year, Aoun released a statement to the Northeastern community, writing, “The terror and bloodshed inflicted by Hamas’s attacks on Israel are cause for the deepest sorrow and most vehement condemnation.” The Oct. 10 statement was the first and last time Aoun addressed the university community regarding the war, which continued to develop for more than a year after Oct. 7, 2023.

“As war now ravages Gaza and Israel, we mourn for all the innocent lives that have been lost. To the many members of our community directly affected by these horrific events, you have our utmost solidarity and support,” he continued.

This time, the message was a bit less decisive.

“We realize that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict ignites strong views on all sides. As an academic institution, we welcome peaceful dialogue and debate that is inclusive of all viewpoints. But we should all be united in our condemnation of terrorism and the killing of innocent civilians,” Aoun wrote.

He similarly contrasts Northeastern’s fundamental values with hate and brutality and points to counseling and mental health resources.

“I do think one of the differences you see between the Ukraine message that Aoun put out and the Israel-Palestine message was that ‘We can say this because we all support Ukraine and nobody’s going to feel bad that we’re supporting Ukraine,’” Leff said.

While student demonstrations in support of Ukraine have received little pushback, the university shut down and criticized several pro-Palestine demonstrations.

Leff said a main difference between the university’s response to war messaging in 1941 and today is the presence of students who have personal stakes in the conflicts.

“In 1941, you didn’t have any Japanese or German students at Northeastern,” Leff said. “You didn’t have to worry about having that population there and how they were feeling and how they’re being treated — it’s part of being more global generally, that the outside world is more present by the time you get to our time period.”

Leff said that whether Northeastern’s duties lie first as an independent institution or as an American institution with its new global standing was a question for Aoun.

“I think in both cases, the university is just trying to keep it from blowing up in their faces,” Leff said. “I don’t know if there’s a lot of conviction there.”

Both statements primarily focus on extending sympathies and support networks to students, as well as welcoming peaceful dialogue and debate from all sides.

“In one case you started with a more powerful country invading another country, and trying to take it over, and in the other instance, you have a terrorist group who massacres 1,200 people,” Leff said. “That’s also an important difference, the statement that they initially put out was Oct. 10, three days after the massacre.”

Universities across the country grappled for the past year with anti-war demonstrations and student calls for institutions to divest and separate from military partnerships.

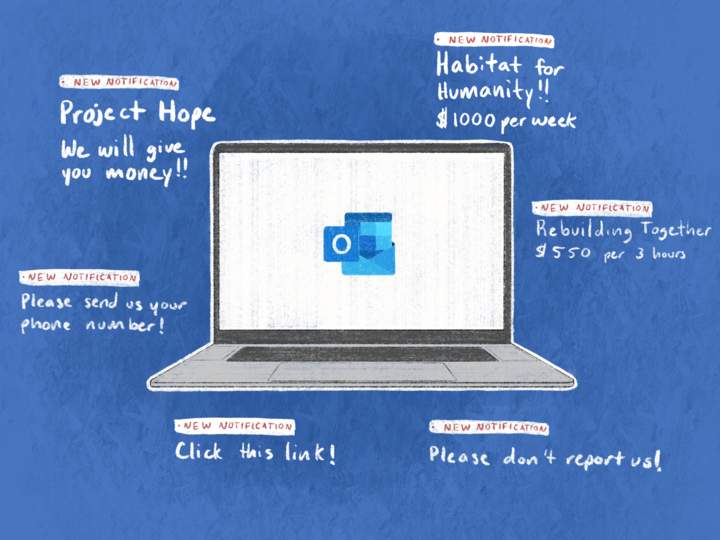

Northeastern shot down calls for divestment and administrative changes in the past year, notably through an online FAQ about the Israel-Hamas war, which echoed Knowles’ statement decades before.

“The university does not impose a political test on employers, nor would we support efforts to curtail students’ experiential learning options. We would hope that students who have strong political viewpoints would not try to impose their views in a way that limited opportunities for their classmates,” the FAQ reads.

Following the April encampment in solidarity with Gaza, the university issued new demonstration policies, which received significant faculty criticism.

“It really is a bigger story about how much people are going to be able to engage in dissent and protest without having to worry about their jobs,” Leff said. “I think that the university got a lot of pushback on this, as they should — I think it’s pretty appalling.”

In December 2024, Northeastern’s faculty senate voted overwhelmingly to reaffirm the body’s commitment to academic freedom and to create a committee to review Northeastern’s freedom of speech policies. Faculty members, citing The News’ reporting, previously criticized the university’s communication and policies requiring provost approval to participate in demonstrations and for encouraging students to report faculty for political bias.

These examples highlight the varying responses universities have had to major international events, often walking a fine line between political neutrality, national solidarity and the respect for various perspectives within their campus communities. After over a year of conflict in Gaza, and a slew of scandals and disputes about institutional messaging, many universities have moved toward neutrality in efforts to avoid more accusations of stifling free speech and academic freedom.

“I think the last four years have shown how difficult it is for universities to strike the right tone on these issues,” Leff said.

For now, at least, President Aoun isn’t telling the university community to go down with the ship.