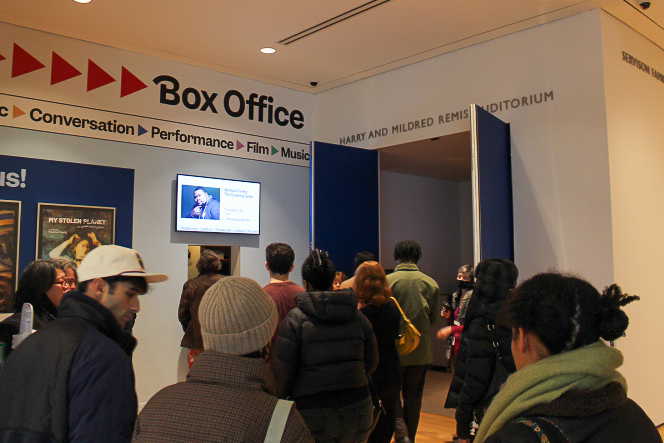

The annual Boston Festival of Films from Iran returned to the Museum of Fine Arts, or MFA, from Jan. 17 to Feb. 7, showcasing seven unique Iranian and diasporic films.

The selection of films featured a wide range of genres and eras, from the award-winning 2024 documentary “My Stolen Planet” to the restored 1974 mystery “The Stranger and the Fog” and more. All of the films were primarily in Farsi with English subtitles.

One of the more recent films shown was “Universal Language,” a 2024 comedy-drama film directed and co-written by Canadian filmmaker Matthew Rankin alongside a cast of Iranian writers and actors. It was Canada’s Oscars entry for Best International Feature Film, named as one of the top five international films of 2024 by the National Board of Review, won the inaugural Directors’ Fortnight Audience Award at the Cannes Film Festival and was called “an Oscar-worthy delight” and “the best movie at Cannes.”

“Universal Language” is set in a surreal fusion of Tehran, Iran, and Winnipeg, Canada, where Tim Hortons serves traditional Persian chai and Québécois commercials play on TV with Farsi captions. The film follows three seemingly unrelated characters whose narratives gradually interconnect until they reach an unforgettable plot twist.

The eccentric mix of cultures and languages in “Universal Language” was disorienting and absurd in the best way. After the showing, filmgoers described it as the Persian love child of Wes Anderson and David Lynch, born and raised in Canada. Ji Li, an activist and service educator who attended the screening, said the film’s true message was conveyed in a more emotional language than Farsi or Québécois French.

“Love is a universal language,” Li said. “In this film, there were a lot of things that had no need to be expressed by any words because there are languages that are nonverbal, like love.”

The film’s atmosphere was foreign yet relatable for the American audiences at the MFA, which Li said was what made it so important.

“There is a lot of trauma, illness and killing in the news [about Iran],” Li said. “I think we need more films like this because people do not trust what they do not understand… It’s very important to bring people together in a film or project that connects humanity.”

Another notable film was the rarely-seen 1977 movie “Dead End,” which was recently restored from the archived 35mm original. “Dead End” was directed by renowned Iranian filmmaker Parviz Sayyad and loosely based on Anton Chekhov’s 1887 short story, “A Lady’s Story.”

Due to the film’s subjective portrayal of women and underlying political themes, it was banned by the Iranian government before and after the revolution. The restoration shown at the MFA was acquired from the UCLA Film & Television Archive in 2012, and the visual and audio damage from the original medium only served to deepen its story.

The film begins as what seems to be a simple love story about an 18-year-old girl enamored with a mysterious man who lingers outside her bedroom window. The protagonist’s daily life is familiar and endearing, from her gossip with her best friend to awkward internal dialogues about her crush. However, the film’s climax jolts the audience back to the reality of pre-revolution Iran. The mysterious man is revealed to be an agent of the government’s secret police, who had infiltrated the girl’s home in order to detain her brother for his political activism.

The film was unique for many reasons, which were discussed after the showing in a conversation with Mary Apick, lead actress in the film, and Ali Banuazizi, a professor of Middle Eastern studies at Boston College.

The two told stories of the film and its context, from Apick’s casting with her real-life mother, Youssefian, acting as her character’s mother in the film to its showing at the Moscow International Film Festival where Apick won her first Best Actress award. They looked back on the portrayal of 1970s Iran in the film, one of a Westernized society that is haunted by government surveillance and political tension, on the cusp of the most profound shift in the country’s history.

“I had tears in my eyes [while watching],” Apick said after the discussion. “All these years, I haven’t seen myself young, being a daughter with my mother, in that light. It just brings back memories, these old, fantastic memories.”

Apick also highlighted the importance of the film’s spotlight on female characters, including the main character, her best friend and her mother in understanding the historical context. Post-revolution Iran has historically forced stringent restrictions on the rights of women, recently garnering global condemnation after Tehran woman Mahsa Amini died under suspicious circumstances while in police custody, later revealed to be a result of injuries due to police brutality. Amini was arrested by the religious morality police for improperly wearing the hijab and the circumstances of her death led to the worldwide Woman, Life, Freedom movement for women’s rights in Iran.

“If you think about how in 1977, this movie was made about women in Iran,” Apick said. “If they focus on [women], it means that the movie industry was to a point to be able and to be accepted to do such a thing.”

Banuazizi described the film’s role in Iranian history, as well as the state of Iranian art today.

“The Iranian filmmakers really have been the vanguards, culturally speaking and politically speaking in art, both before the revolution and after the revolution,” Banuazizi said. “I don’t want to limit it only to the political dimension by any means because they are artistic productions. But the role of filmmakers in Iranian society has been really quite remarkable.”

Banuazizi said that one of the primary benefits of showcasing Iranian films like the MFA’s festival is how it conveys Iran’s culture differently than negative news.

“It’s so good to see the cultural side of Iran, rather than merely hearing about the punishment,” Banuazizi said. “That’s the value in films like these, that they present the Iranian culture not only from the perspective of Islamism, but from a much more humanistic and artistic side.”

Katherine Irving, senior programmer of films at the MFA, began selecting films for the festival back in November 2024. She said that out of all the films she watches for the MFA’s various film festivals, Iranian cinema stands out.

“Honestly, the Iranian Film Festival is one of the highlights of my year,” Irving said. “It’s the most fun to program. Iran reliably turns out great films every year.”

Iranian cinema has been hailed as the home of some of the world’s greatest films, earning countless awards from international film festivals throughout its history. Irving said that the success of Iranian films have been not simply in spite of, but instead because of, severe content censorship by the Iranian government.

“Every year, [the festival] gets more and more impressive, honestly, because the restrictions around art are getting more and more stringent, and people in Iran are willing to risk their lives for their art in a way that I haven’t seen in very many other cultures,” Irving said. “It’s incredibly impressive, the work they manage to do every year.”