Struggling with unrealistic beauty standards is a harsh reality for women, especially for those in the entertainment industry. When faced with a way out, a way that could bring happiness and security in one’s own skin, it can be difficult to not be blinded by possibility. Heavy is the hand that holds The Substance.

That sketchy, lime-green experimental drug Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore) uses takes the name of French filmmaker Coralie Fargeat’s sophomore feature. In “The Substance,” network executive Harvey (Dennis Quaid) fires Elisabeth, a former actress and current aerobics TV host, on her 50th birthday when he deems her to be too old to continue hosting her show. In a desperate attempt to not fade into obscurity and reclaim her youth, Elisabeth uses the titular Substance that promises a younger, more “perfect” version of oneself. Once injected, Elisabeth’s back splits open in a gag-inducing way and out climbs Sue (Margaret Qualley), the wrinkle-free and perfectly toned younger clone. Her first action? Audition for Elisabeth’s vacant host position and skyrocket to 1980s-esque aerobics fame.

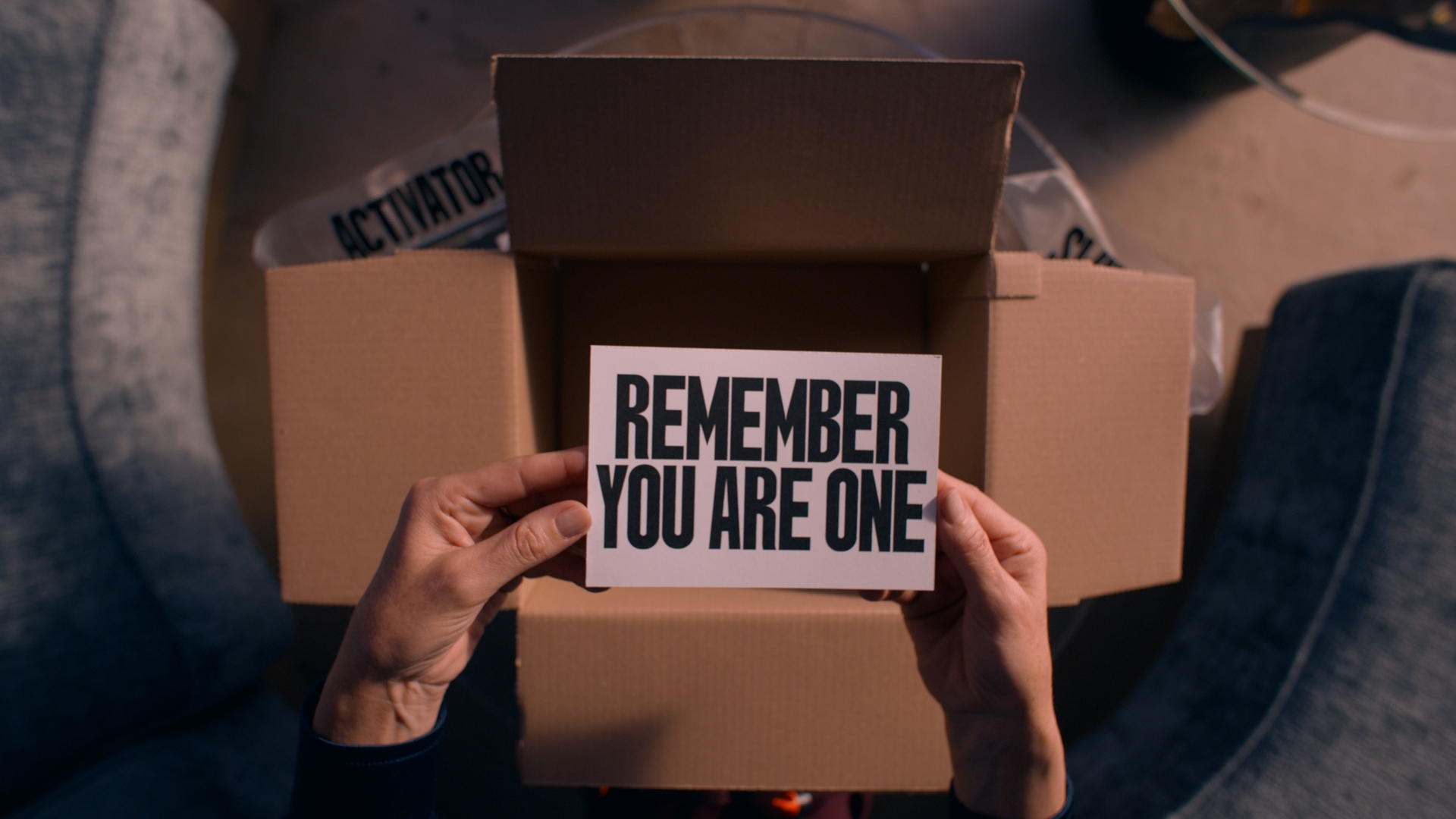

The Substance’s instruction manual comes with an uncompromising set of rules: Elisabeth and Sue must switch consciousness every seven days. One gets to be out in the world living as normal, while the other lies naked and comatose on the bathroom floor. Any hope that the two women will follow these conditions to a tee and happily “respect the balance” is soon shattered — thus, the body horror begins.

Chaos ensues as Sue consistently fails to honor the switching schedule, with Elisabeth facing the nasty physical consequences. It starts with a rapidly-aged index finger and progresses into someone almost otherworldly.

Moore has been dominating the Best Actress race this awards season, having won both the Golden Globe and Critics Choice so far for her portrayal of Elisabeth. Her distress, depression and horror at every turn of events is delicately acted. It takes a monster of an actress to put on as physical and raw of a performance as Elisabeth requires, and Moore did not disappoint. Qualley’s turn as a vapid, “sexy-and-she-knows-it” TV star is a bit one-dimensional, but pointedly so — Sue was created to be youthful, after all, so the expectations for her emotional depth were not all that high.

By far the most impressive part of the film’s production is its Oscar-nominated makeup and prosthetics, a Herculean effort led by makeup artist Pierre Olivier Persin. As Elisabeth begins to reel from the repercussions of Sue’s abuse of The Substance, she steadily transforms into more grotesque versions of herself, a feat accomplished by a severe but necessary lack of CGI effects.

Persin and his team used materials including gelatin, plasticine, silicone and clay to create monstrous evolutions of Sue and Elisabeth that must be seen to be believed, requiring bouts in the makeup chair lasting from 45 minutes to six hours. The special effects are dialed up to 100 during the film’s last 20 minutes, which required 30,000 gallons of fake blood to give its full gory effect. The sheer scale of prosthetics used won’t earn this movie the Oscar, but the small details and realistic look of them will.

Equally as squirm-inducing is the sound design of “The Substance,” which elevates every noise to its absolute maximum. The Substance-injected egg yolk from the opening scene squelches and gurgles as it duplicates, Harvey messily slurps down mayonnaise-covered shrimp as he fires Elisabeth and the score is built around thumping, twisting basses and synths that are almost a sensory overload on the ears. It’s meant to make you wince, a sign that you’re paying attention to those intricacies.

By the end of the 140-minute movie, the message it’s trying to send is abundantly clear — a woman’s experience with internalized violence rooted in female beauty standards can be vicious, with its potential solutions becoming dangerously addictive. Until the end credits start rolling, Fargeat leaves shockingly little to the imagination, and the film is better for it. Beauty is skin deep here; “The Substance,” however, is not.