by Nick Marini, social media manager

As much as I love a good new movie release, I still favor revisiting older classics. Movies that have stood the test of time, proved their worth after multiple viewings – ones worth owning. I figured it was time for a retro review – time to take a look back and talk about an impactful, relevant movie of the past.

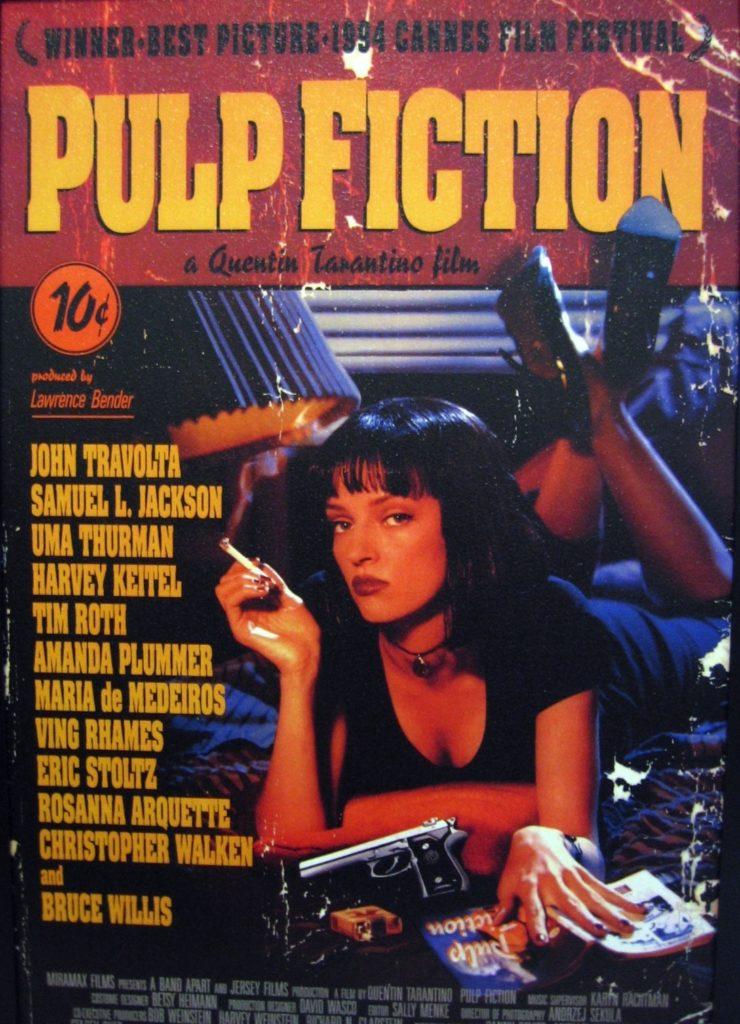

20 years ago, the year 1994 happened. What a year it was for movies, something of a watershed for beckoning in the modern age of visual storytelling, fresh off the special-effects wonder “Jurassic Park.” We saw smash hits like “Forrest Gump,” got an emotional epic in “The Shawshank Redemption,” saw an indie achievement in “Bullets Over Broadway,” welcomed white knuckles and sweaty palms with “Speed,” forged childhood memories with “The Lion King,” got stupid with “Dumb and Dumber,” got magical for “Angels In the Outfield” and got plain silly with “Ace Ventura: Pet Detective.” (Big year for Jim Carey, huh?) However, most importantly, we got the Palm d’Or winner from Quentin Tarantino, “Pulp Fiction.”

A lesson in screenwriting and a clinic in charm, this movie is every film major’s best friend. It is however, for good reason. After rewatching “Pulp Fiction,” it’s hard to ignore the dialogue. Roger Ebert once said it’s the best movie that could be played back as an audiobook, and I can’t agree more. What the characters have to say doesn’t serve to advance the plot like most movies. Instead, exposition comes through much more indirect ways – through sets, clothes and the random conversations we hear the characters have, the audience is challenged to connect the dots for themselves. It doesn’t matter what they’re doing, the characters have interesting things to say and relentlessly indulge in material that bleeds cool and justifies laughs.

The film is as quirky and whimsical as it is violent and bizarre – like a drugged-up, colorblind, R-rated Wes Anderson movie. Characters are odd and specific for the sake of being, well, odd. This isn’t a movie based on real life, but wacky and entertaining situations that could only be thought up while taking inspiration from other movies. It’s like a self-aware Raymond Chandler novel that fell off the deep end and just got too damn weird. How else can you explain how Tarantino handles the result of the should-be climactic face off between Butch and Marcellus? He constantly warps traditional tropes in favor of riddling the audience with bizarre situations. Plus, there’s a gimp.

Segmented into seemingly unrelated blocks that play out like chapters in a pulpy noir novel, the audience is again challenged. (Note, this is a specifically different type of “challenge” for the audience. It’s not an exercise in film study to analyze the movie, like an art house drama. Every “challenge,” for lack of a better word, is woven into the story. You want to know what’s going on? Follow the labyrinthine dialogue.) In order to follow the story, the viewer needs to be patient. Cutaways are tied into flashbacks, like in “The Gold Watch” segment.

While he claims to have not made a noir movie, it’s hard to deny Tarantino’s noir influences – the whole boxing set up, the scene with Esmeralda and Butch after he doesn’t throw the fight, the hard-boiled dialogue, moral ambiguity, the necessity, and failure, for characters to change, the list goes on. Still, it’s far from traditional noir or gangster, melding generations of influences into something of a verbal roller coaster. It’s a blockbuster not of special effects, but writing.

Much like his preceding effort “Reservoir Dogs,” the story is intertwined and nonlinear. Sometimes, a character monologue tells us what we need to know (“Gold Watch” segment and Jules’ revelations). In a lesser movie, these would dull down the plot and add unnecessary minutes to the runtime. Not here. Other times, like the opening “Royale with cheese” conversation and the Tony Rocky Horror backstory, we learn remarkable amounts about characters in very indirect ways. Again straying from traditional form, we aren’t shown or told, because character traits are discussed in inventive and flashy ways. When we see Marcellus’ face for the first time late in the movie, but we immediately know who he is, and we already know so much about him. He had been talked up off screen multiple times, allowing the audience to mythologize a character we hadn’t met yet, as we often do with celebrities and artists whose work we admire.

Tarantino is notorious for creating these nonlinear segments that don’t advance each other’s plot, but enrich the characters and the events that occur within them. What good is Butch without that gold watch story? How threatening could Marcellus be without all the things we heard about him? Poor Tony Rocky Horror…Each segment, then, has a distinct beginning, middle and end, creating mini stories and anecdotes within a larger encompassing story that involves all the parts in unique ways. It’s a main tangent with three distinct branches, and scenes-as-cutaways that deepen the connection within branches.

Another lasting quality is the way Tarantino packs every single element of his story with something unique and memorable. Nothing is left untouched. He didn’t have to play Jimmie as such an idiosyncratic weirdo, but he did and it enlivened the character. Mr. Wolf didn’t need to have militant directness, but as a result he became Mr. Wolf. Whenever there’s an opportunity to add something random and interesting, he flushes the script full of it.

These people have unremittable coolness. He’s used influences from eons of watching movies and brings in a pulpy kitsch that is undeniably entertaining. It’s weird, hard to follow, disconcerting, quirky, violent and disturbing. There’s a strange dynamic at work of summating so much traditional form and content and spinning it in a way that hasn’t been seen before. There are too many influences to count in “Pulp Fiction,” but at the same time, is there really another movie that’s like it? Tarantino used influences in a way that created new ones – a new take on classic methods and a classic take on fresh disposition. It’s essential filmmaking, a complex but straightforward way to pay joyous homage to all the celluloid coming before it that put asses in seats. 20 years later, it’s still doing it.

Photo courtesy of Roman Soto, Creative Commons