By Kelly Kasulis, News Staff

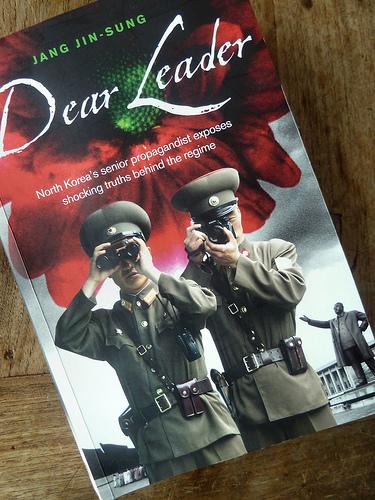

Happy endings are somewhat of a myth, even for the North Koreans that escape deadly grips in a grueling, month-long pursuit. That’s one lesson readers must come to terms with when reading Jang Jin Sung’s groundbreaking 2014 memoir, “Dear Leader: Poet, Spy, Escapee – A Look Inside North Korea.”

North Korea is an isolated nation accused of a startling number of day-to-day human rights violations, including detaining an estimated 150,000 to 200,000 people in prison camps akin to those of the Holocaust, according to a 2011 report published by Amnesty International human rights network. In the past, best-selling memoirs like Blaine Harden’s 2013 retelling of activist Shin Dong Hyuk’s escape from North Korea have drawn attention to the increasing number of people finding refuge in China, South Korea and the United States.

For years now, the globe has had firsthand accounts of the vicious torture, public execution, mass starvation and other cruelties inflicted upon North Korean people. Many of them, like Shin Dong Hyuk, were prisoners of camps.

But with Jang Jin Sung’s book, something new is offered: an intimate look at the administrative subjugation now-deceased North Korean leader Kim Jong Il had on his people.

Jang Jin Sung was born to a family with reasonable wealth because of their loyalties to Kim Jong Il, where he was first bred to be an acclaimed pianist until he was later given the rare choice to study the written word instead. Sung led a comparatively fortunate life, receiving a quality education and later being granted a brag-worthy job in the capital, Pyongyang, producing propagandic epic poems about Kim Jong Il’s godlike glory. He also was tasked with revising and rewriting history, granting him exclusive access to foreign newspapers and old documents containing North Korea’s original history.

In 2004, when he lent a forbidden newspaper to his equally-disenchanted friend, Young Min, who accidentally left it on the train, the two had no choice but to defect to China.

Here are the greatest discoveries from Jang Jin Sung’s retelling of this journey:

1. Kim Il Sung, North Korea’s original leader, never wanted Kim Jong Il to succeed him.

In fact, by the time Kim Il Sung died, he was merely a figurehead puppeteered by his son. Kim Jong Il essentially had all of his competing candidates purged – killed – fostering a culture where a large number of North Korea’s “admitted” first class were murdered in a Red Scare-like hysteria to accuse the other of disloyalty to avoid being purged themselves. Many of Kim Il Sung’s comrades, whom he battled with in the Korean War and founded the nation of North Korea alongside, were also killed or systematically removed from power. Kim Il Sung’s dying wish was to be buried among these comrades, which Kim Jong Il promised, though he instead used his father’s mummified body as a propagandic sculpture.

2. Disillusioned, angry North Koreans exist.

Footage of North Korea’s unified Arirang arts festivals and mass grieving of both Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il’s deaths have created an impression that all North Koreans are brainwashed to unconditional loyalty. Although Jang Jin Sung explains that many truly believed Kim Jong Il only ate a rice ball a day in solidarity with his starving nation, he also illustrates gruesome images of a very discontent and impoverished class. In the more rural areas, including his hometown, where public executions and selling women for food were commonplace, there existed a type of citizen that despised their “dear leader” openly in surrendering realization that they would not live long anyway.

3. North Korea functioned on Kim Jong Il’s “old boy’s network,” which could mean something for present leader Kim Jong Un.

Kim Jong Il had his schoolmates at his side, a camaraderie that Kim Il Sung mirrored with his fellow soldiers in the Korean war. But Kim Jong Un, who spent a large portion of his childhood being educated in Switzerland, does not have similar connections. Jang Jin Sung and many others speculate what this could mean for a continued consolidated power in North Korea, a nation whose positive foreign relations has since waned, including a decrease in international aid – mostly because it was being distributed in overwhelming portions to the “admitted” class, allowing a large percentage of the population to perish from starvation.

Photo courtesy Creative Commons, Screenpunk