By Maxim Tamarov, news editor

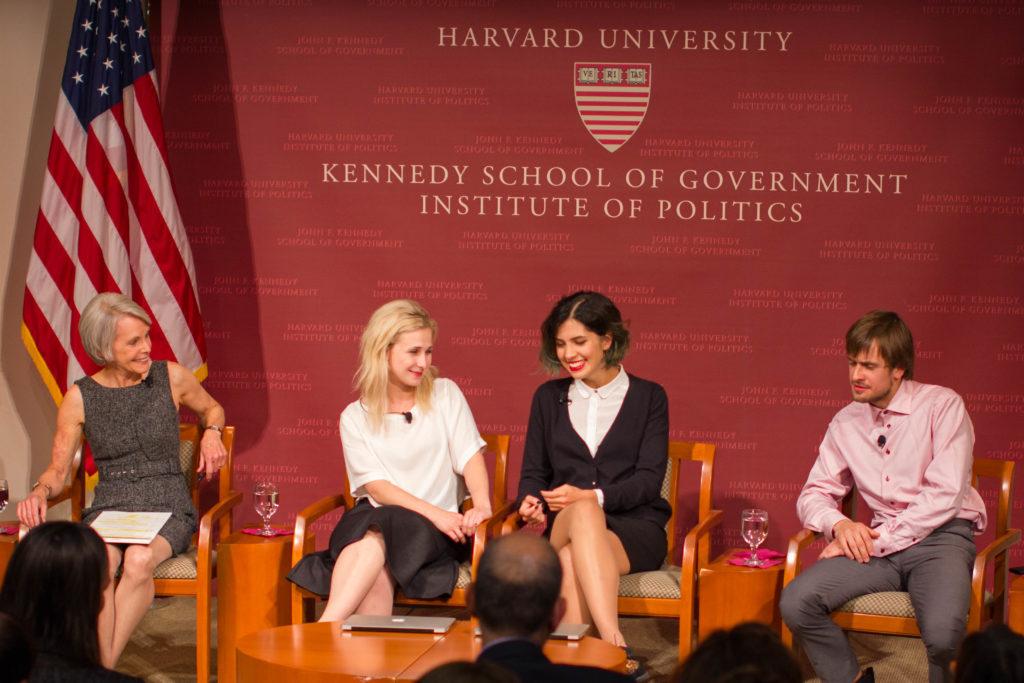

Monday night saw Masha Alekhina and Nadya Tolokonnikova, political activists and founding members of punk rock outfit Pussy Riot, engaged in a dialogue about Putin’s Russia, civil disobedience and methods of protest held atHarvard University’s Kennedy School of Government.

“[Our goal is] to protest against Putin and convey our message as brightly as possible, as strongly as possible,” Alekhina said. “There really is a big urge among ordinary Russians for change. The problem is that the time is not right, and the people do not see the right method.”

The forum, hosted by the Institute of Politics (IOP) and moderated by former CNN foreign affairs correspondent and Woodrow Wilson Public Policy Scholar Jill Dougherty, was a sold-out event. Tolokonnikova’s husband, Peter Verzilov, acted as translator for the group.

Pussy Riot has made headlines in Russia and across the globe for their February 2012 performance in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow of a song entitled “Mother of God, Drive Putin Out.” They were arrested for “hooliganism” and were forced to spend two years in a penal colony.

“You can say that the action was the most conservative of Pussy Riot action,” Tolokonnikova said. “We wanted to take away the church from Putin and give it back to religion — to Jesus.”

In 2014 Pussy Riot made headlines again after being beaten with whips by pro-Kremlin supporters for a protest against the Winter Olympics in Sochi. Both times the group was clad in vibrant ski masks while performing songs that were vehemently critical of Putin.

“Besides our activity with Pussy Riot, we’ve opened up a news outlet and an NGO,” Alekhina said about the duo’s alternative approaches in response to a question about their in-your-face public stunts. “We also looked for much more calm and much more legal ways to work with political groups in Russia.”

Alekhina and Tolokonnikova explained that they learned a lot from fellow political detainees during their time in prison. They said that besides the horrors of prison, they witnessed personalities and courage that motivated them further upon their release.

“Uniforms, whether military or prison, create a huge wall between society and prisons [in Russia],” Alekhina said. “When people speak of prison, they become serious.”

In a country where political unrest is handled with an iron fist and people are afraid of the government, the members of Pussy Riot have found hope through occasional glimpses of humanity in Russia’s most unlikely corners.

“The first autograph I gave [was] to a convoy guard while being transferred from one prison to another,” Tolokonnikova said.

Another guard allegedly told Pussy Riot that they were brave for what they were doing and that he supported them — as he lead the duo to the police vehicle outside.

Such irony is not uncommon in a country where 27 percent of the population admit they vote for a certain candidate due to fear of prosecution, according to Tolokonnikova.

“We had elections [for mayor of Moscow],” Tolokonnikova said, describing a close political race. “One of the candidates managed to garner almost the same amount of votes as those who had financial backing [from the government]… Now he is under house arrest.”

Alekhina and Tolokonnikova explained that the mission of their travels was to adopt a more critical view of the west, which is often idealized by those in the Russian opposition. Both she and Tolokonnikova pointed to such problems as the prison situation in the US and migration in Australia. They wanted to learn more and inspire a self-critical approach to foreign supporters.

“When Putin invaded Ukraine, he often appealed to US aggressive foreign policy,” Tolokonnikova said. “’The US first invaded everyone else and now they’re complaining about it,’ [according to Putin].”

Pussy Riot expressed great appreciation for their fandom and supporters, but despite their popularity abroad, they said that it is the Russian supporters who meant the most to them.

“You have to realize that people here can support us in comfort, but in Russia, you are in danger if you support us,” Tolokonnikova said. “Cold water was spilled on [those gathered outside the courtroom after our arrest], and they were beaten up — that kind of support is incomparable to the kind of support that came afterward.”

Monday night also saw the duo speaking to Harvard alumnus Roman Torgovitsky, who was present at the forum illegally and spoke out in support of the Russian dissidents.

“Institutions simply ignore activists,” Targovitsky said during the Q&A period at the end of the forum. “I want to express gratitude for you coming here and for being so brave in your protest in Russia.”

Torgovitsky was arrested for disorderly conduct in May after jumping on stage to protest Vladimir Spivakov’s support of Putin during a concert by the Russian composer at Sanders Theatre in Moscow.

He was arrested again after the IOP forum, because he was banned from Harvard’s campus after his previous arrest. Pussy Riot and other supporters went to the Cambridge Police Department after the forum to bail out Torgovitsky, according to the group’s Twitter page.

“We are very disappointed that a person like Roman was banned from Harvard grounds for voicing his opinion in what we thought was an adequate form,” Tolokonnikova said.

Photo by Shawn Simpson

![A demonstrator hoists a sign above their head that reads, "We [heart] our international students." Among the posters were some listing international scientists, while other protesters held American flags.](https://huntnewsnu.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/image12-1200x800.jpg)