By Olivia Arnold, news correspondent

As Ebola continues to spread and public concern rises, Northeastern professor Alessandro Vespignani has developed a model to predict the spread of Ebola in Africa and across the globe that has been featured in publications from The New York Times to The Wall Street Journal.

“[The spread of Ebola in western Africa] is like having a big fire in one place of the world, and from time to time some of the sparks of this fire are going out [to other] places in the world,” Vespignani, the Sternberg Family Distinguished Professor of physics, computer sciences and health sciences, said. “And obviously, the more sparks go around, the more likely they could start another major fire, and we don’t want that. So the only way to really extinguish the fire is in West Africa.”

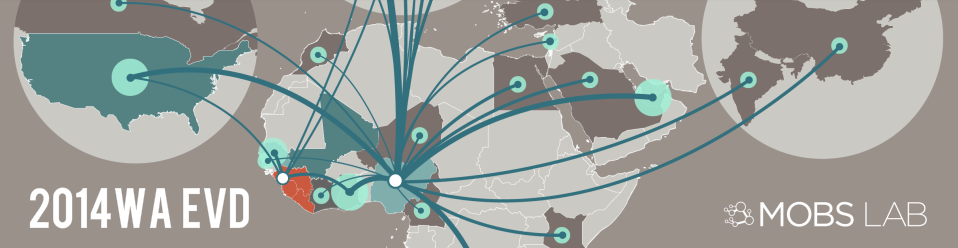

Vespignani, along with his team at the Laboratory for the Modeling of Biological and Socio-Technical Systems (MoBS), have utilized the Global Epidemic and Mobility Model to create a synthetic computational world that takes into account information on population, demographics and mobility patterns. Vespignani’s work was published in the “Public Library of Science (PLOS) Current Outbreaks” on Sept. 2.

Vespignani was originally involved in tracking the spread of computer viruses, and he realized that the same techniques could be manipulated to predict the spread of infectious diseases.

“Why don’t we do epidemic forecasts like we do in weather, what’s the problem?” Vespignani said.

In 2011, Vespignani moved from Indiana University to Northeastern as a professor in the College of Science and the head of MoBS, where he continued to produce epidemic forecasts. In July 2014, when the Ebola virus disease was taking off and making headlines, Vespignani aimed to understand the growing epidemic and set up a usable model. As the number of Ebola cases in western Africa began to increase exponentially, Vespignani and his team started full-scale analyses of the virus to try to model its spread both in western Africa and internationally.

Vespignani’s research focused on three African countries: Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia. He predicted that the total number of cases from the West African regions would double about once a month.

Richard Wamai, an assistant professor of African American studies at Northeastern, said that studies like Vespignani’s are valuable to the health and international communities in gathering critical data and providing guidelines for future preparedness and aid.

“The fact that the outbreak happens in those [West African] settings tells us that the preparedness of the health system is weak, and also that preparedness in the global health community is also weak,” Wamai said.

Vespignani likened the Global Epidemic and Mobility Model to a weather forecast prediction that is subject to deviations, but provides numbers that can “bring some rationality to the discussion” for politicians and policymakers wanting to make informed decisions on how to address the disease.

“[The Global Epidemic and Mobility Model] is basically a platform that allows us to combine specific disease dynamics, [which create] a framework that takes into account geographic and demographic conditions,” Marcelo Gomes, Ph.D., a member of MoBS, said. “The short-range [mobility] would [show the] daily mobility flow of individuals, for instance, from one town to another, [whereas] the long-range mobility is monitored through an air traffic map. This information is then used to assess the number of individuals that go from one area to another.”

The Ebola modeling conducted by MoBS is unique in that it did not just consider air traffic to and from West Africa, but it also took into account the mobility and interactions of individuals and passengers. Vespignani also considered transmissibility – how the disease is spread – as a “key parameter” of his research. In West Africa, disease is mainly transmitted at hospitals and funerals when family or community members come into contact with an infected person’s bodily fluids.

Michael Pollastri, an associate professor of chemistry and chemical biology at Northeastern, called Vespignani’s research “compelling.”

“I think the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control are clearly paying attention to his predictions because he has actually been pretty accurate,” Pollastri said.

Vespignani listed the US, the U.K., France and Belgium as non-African countries with the highest risks of contracting Ebola cases. On Sept. 30, the US had its first Ebola case when Liberian national Thomas Eric Duncan contracted the disease abroad and then reentered the US . Since then, there have been three Ebola diagnoses in the US, two of which were nurses who treated Duncan. Duncan is the only Ebola related death to have occurred in the US, but Nina Pham and Amber Vinson contracted the disease after caring for Duncan, and New York doctor Craig Spencer was diagnosed after returning from Guinea.

Vespignani called the accuracy of his predictions “a peculiar situation.”

“Unfortunately, for the entire month of September, things were following our predictions,” Vespignani said. “We do the predictions, but then if they [show] a worst case scenario, we hope that they will not hold.”

For the month of October, Vespignani noted that things have started to slow down in West Africa, but that it is too early to tell if that is due to international action or an underreporting of cases.

“I think in a pessimistic way, this will still be ongoing for a couple of months,” Ana Pastore y Piontti, a member of MoBS, said regarding the future of Ebola. “The optimistic way will be that at least other countries are helping and eventually this thing will be over.”

For November and December, Vespignani predicts a low probability of 10-20 percent that the US will see another Ebola case. Although one to two more cases are likely before the month’s end, Vespignani is confident that the American healthcare system is well-equipped to handle it.

“I don’t expect that we could have an epidemic of Ebola in the United States, or even a large outbreak. I’m pretty confident of that,” Vespignani said. “The only problem for the United States or other countries would be if this fire extends to other places in the world.”

In West Africa, however, the number of cases are still increasing. Sierra Leone is dealing with a steady increase, while Liberia and Guinea seem to be fluctuating in regards to improvement. As Ebola cases in West Africa increase, so does the US’s risk of receiving more cases.

“This hopefully can be a wakeup call to say, ‘look, diseases in the developing world are not things we should ignore, because it’s going to become our problem too,’” Pollastri said. “We ignore these things at our own peril.”

Despite wavering opinions of optimism and pessimism regarding the models and spread of the disease, Vespignani, is “optimistic” about how the Ebola situation will progress.

“I am less worried than where I was one month ago, because one month ago I was just looking at this situation that looked out of control and interventions were not obviously enough and the international community was not mobilized enough, and now instead all those things are coming along,” Vespignani said. “So I’m optimistic that we will be able to hopefully in some months to have a complete different situation in West Africa so that we are much more safe.”

Graphic courtesy Nicole Samay, MOBS LAB, Northeastern University