By Sam Haas, news correspondent

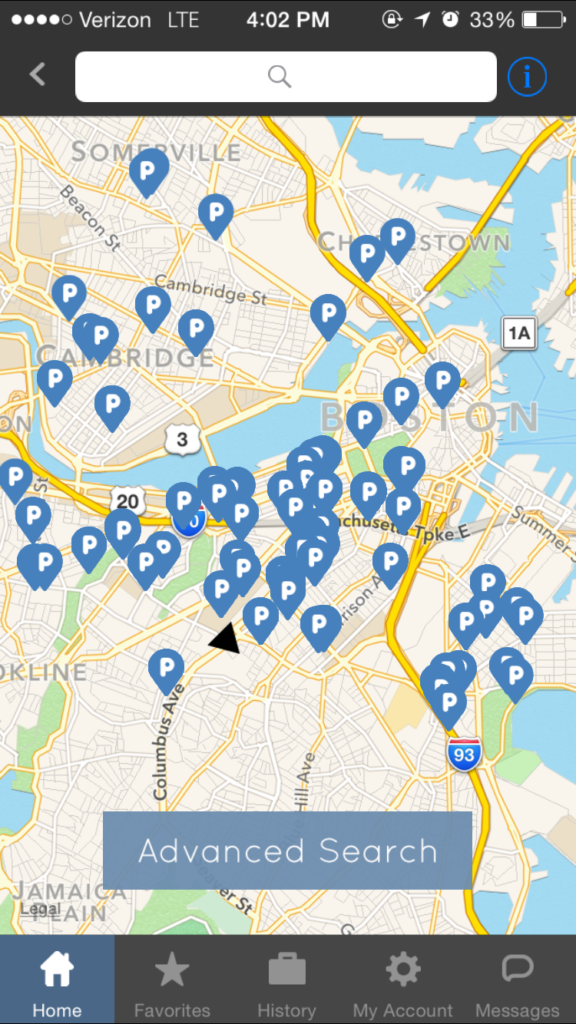

Four months after officially launching in Boston, parking spot-sharing app SPOT is thriving.

SPOT, founded two summers ago and debuted in December, enables users to rent private spaces from each other for hours, days or weeks at a time. Owners register spaces, provide location details and set a price. Renters can then reserve a particular spot through the app. The company takes a cut of the money and passes the rest on to the space’s owner.

“We’re creating a tool that allows people to park more easily in a big city,” CEO and founder Braden Golub said. “It’s a win-win for the spot owner and the spot renter.”

Golub’s inspiration for SPOT came when he noticed that many private lots near his apartment were empty while his girlfriend often parked a half-mile or farther away, which meant he had to get up early in the morning to feed a meter.

“I thought, ‘Why can’t my girlfriend use one of those spots?’” he said. “I’d gladly pay the owner whatever they wanted.”

SPOT’s appeal is its convenience, ease of use and low prices, according to Vice President of Product Operations Mark Abramowicz.

“The concept is an efficiency play,” Abramowicz said. “It’s cheap, convenient, quick, cashless.”

It is also, crucially, legal.

Last summer, a short-lived startup called Haystack allowed users to essentially rent out public parking spaces. The app encountered a storm of criticism from residents and Mayor Martin J. Walsh until Councilor Frank Baker introduced an ordinance to ban the sale, lease or rental of public spaces. The ordinance passed unanimously, shutting Haystack out of Boston.

The major distinction between SPOT and Haystack is SPOT’s focus on private spaces, which the city cannot really control, according to Golub. But even if it could, he said, it wouldn’t want to.

“We had four or five meetings in the two months prior to launch. They were really receptive,” Golub said. “SPOT incentivizes people to go into the city because they can park here.”

Down the road, Golub envisions the possibility of a direct relationship with the city. Although he hasn’t had any conversations with officials about a relationship, SPOT’s growth — which Abramowicz pegged at 400 percent per month since December — has made him hopeful.

“We’ll eventually be able to go to them and say, ‘Hey, this is something that provides value to all of your residents,’” Golub said.

Golub plans to introduce SPOT to six other US cities, starting with Chicago this summer. The SPOT team, he said, had received strong enough feedback from Boston residents that they felt ready to expand.

One of these Bostonians is 36-year-old Jamaica Plain resident Tammy Scarlett. Scarlett started using SPOT in September after someone she volunteers with recommended it.

“It’s so brilliant,” Scarlett said. “The rates of parking, comparatively,– it only makes sense to use SPOT.”

She uses the app mostly to findspaces for an hour or two when volunteering, attending classes at Harvard University or conducting research at a Harvard-run lab. To her, the biggest advantages of SPOT are its flexibility and convenience.

“Transportation is a juggling act,” she said, “but SPOT has completely taken that off my plate.”

Freshman political science major John Hughes has also struggled to make parking work with his busy schedule. Unlike Scarlett, he hadn’t heard of SPOT, but the app’s potential excited him.

“If the price is lower than or comparable to parking garage prices, it’s something I’d use for days,” Hughes said. “I’m going to look it up right now.”

Scarlett also praised the company’s community service team. Mitch Gaynor, SPOT’s head of marketing, helped her find available spaces when the one she usually uses was buried during a blizzard.

“I really get the sense that what their company is all about is being a go-to for the customer,” Scarlett said. “I hope that more people get engaged and list their spots. It would make Boston a well-oiled machine.”

However, transforming Boston into a parking paradise may be overly optimistic. The neighborhoods with the most private spaces are not the ones that attract the most commuters and visitors, according to George Thrush, director of Northeastern’s School of Architecture and a professor in the School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs.

“It could help, but I suspect where parking is in highest demand, it’s not going to make a lot of difference,” Thrush said. “Asymmetry between supply and demand will probably limit its impact.”

Even so, Golub and Abramowicz assure their app will be a boon for the people of Boston.

“We don’t really think that we’re enabling people to make money,” Abramowicz said. “I think what we’re trying to do is help them.”

Photo by Scotty Schenck