Lower Roxbury Black History Project unveiled

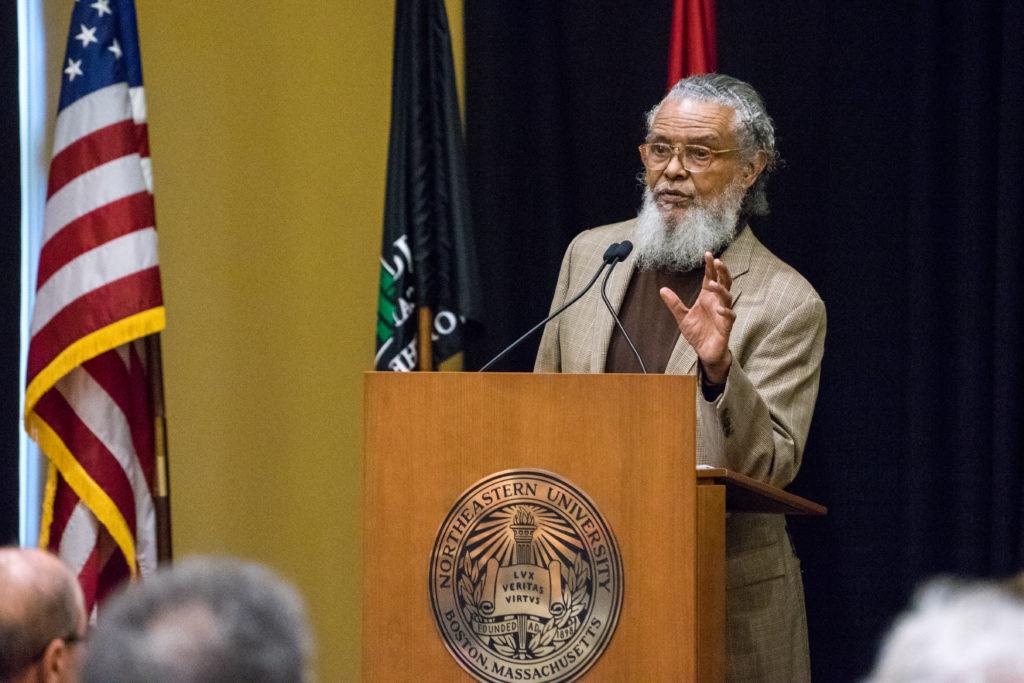

State Rep. Byron Rushing (D-9) speaks at the John D. O’Bryant African American Institute on Tuesday as part of the opening of the Lower Roxbury History Project. / Photo by Lauren Scornavacca

April 20, 2017

In 2006, newly-appointed Northeastern President Joseph E. Aoun began collaborating with leaders in the Lower Roxbury black community on a preservation project – one that would take 11 years, a task force and the archives staff at Snell Library to complete.

The Lower Roxbury Black History Project, now accessible on Snell Library’s website, was unveiled Tuesday at a reception in the John D. O’Bryant African-American Institute. The collection contains photographs, digitized artifacts and 47 interviews with longtime residents of the area.

State Rep. Chynah Tyler (D-7), a Northeastern alumna and fifth-generation Roxbury resident, spoke at the reception about the importance of documenting Roxbury’s history as the neighborhood changes.

“Back in the 50s, the 60s, the 70s, it was very lively,” Tyler said. “There were jazz clubs, there were community groups that really were unified and there was a sense of community in general. What’s interesting about it is people were proud to be from Roxbury. It’s important to capture that because it’s much different than it was back in those days today.”

The project was set in motion after the 2006 meeting between the university and members of the Black Ministerial Alliance in Roxbury to discuss how Northeastern could collaborate with the community. Photographer and documentarian Lolita Parker Jr. was then hired to interview elderly members of the community and archive photos, maps, documents and other artifacts.

Between 2007 and 2009, Parker interviewed more than 40 members of the Lower Roxbury community with her son, photographer London Parker-McWhorter.

Parker said the people she interviewed frequently brought up concerns about the way Northeastern was changing its surroundings. She also said while she acknowledges Northeastern’s role in driving out previous residents, it is not fair for individuals to direct all their anger at the university.

“There are many neighborhoods that are being gentrified right now that aren’t around major universities,” Parker said. “I travel a lot; I see it everywhere. It’s just a lot of poor white, black, brown people being pushed out of neighborhoods that were once undesirable. I don’t think it’s specifically that Northeastern is the big bad wolf, they’re just a part of something that’s going on everywhere.”

In his speech, State Rep. Byron Rushing (D-9) said creating an archive of documents from Roxbury is an important way to preserve the way of life in a neighborhood destroyed by new development.

“I can go and take you to the home of a black Revolutionary War veteran and show you his house on Beacon Hill, and I cannot show you the house of [Rev.] Michael Haynes in Lower Roxbury,” Rushing said. “I cannot show you those buildings because those buildings, for no other reason but greed and race, were torn down.”

He also said that while historical Lower Roxbury is gone, it still exists in the memories of the people who lived there.

In response to a question about Northeastern gentrifying Roxbury, university spokesperson Matthew McDonald said he questioned the accusation that Northeastern was expanding into the neighborhood.

“Having attended yesterday’s event and having worked at the university for a number of years, I question the premise of your claim about Northeastern’s ‘ongoing expansion into the neighborhood,’” McDonald said. “Rep. Rushing did speak about the destruction of parts of Boston neighborhoods during an earlier time in the city’s history, but his comments were not related to Northeastern.”

McDonald also said Northeastern invests in a range of programs to help the community.

“Northeastern and its neighbors in Roxbury continue to work closely on a range of programs, including the university’s low-interest loan program for local businesses, the Youth Development Initiative Project, STEM programs for Roxbury youth and many others,” McDonald said in an email to the News.

Rachel Domond, sophomore sociology major and member of Students Against Institutional Discrimination’s anti-gentrification campaign, said the project was a way for Northeastern to pretend to be a community ally to Roxbury while continuing to gentrify the neighborhood.

“If you think about it, this project is commemorating a history that Northeastern has played a role in completely destroying,” Domond said. “The reason that so many buildings are being torn down and people are being displaced and people need to leave is that Northeastern came in and took over all the space.”

For the past nine years, university archivists have transcribed and organized the interviews into a searchable web version. Giordana Mecagni, head of archives and special collections at Snell Library, said by establishing audio and video records of Roxbury residents, viewers are now able to see their personalities. She said the project gives people a deeper understanding of the neighborhood and its residents.

“One of the great parts about oral histories is that you can learn a lot from documents, but it’s very hard to learn the personal experience and color of what a neighborhood or group was like without talking to them personally,” Mecagni said.

Over the 11 years the project took to complete, Mecagni said better digital tools and technology were developed to host the content. Despite the long wait, she said the end result is worth it.

“Even five years ago it wouldn’t have looked as pretty, just because the technical infrastructure wasn’t there,” Mecagni said. “Stars aligned for this to happen. It did take a long time for us to catalog everything and make sure everything was findable, but it happened at the right time.”

Mecagni said organizations in the community have told her they were grateful to have Northeastern preserve Roxbury history.

“Sometimes having an organization with climate-controlled storage – an archive, a true archive with climate-controlled storage and specialists making sure that everything is still there and organized and described is actually easier for community based organizations,” Mecagni said.

Tyler said her own exploration of her family’s history and photographs motivated her to join politics and help her community. She said she hopes this project can do that for others, like her young daughter, who are now growing up in Roxbury.

“My family’s been here for five generations,” Tyler said. “Had I not seen photos or anything really tangible that I can see happen back in those days, I wouldn’t be inspired to do what I do today.”