The Rainbow Disconnect: How the LGBTQA+ community fails to support all members

Northeastern students shared their experiences in the LGBTQA+ community. From left to right, Sara Atlas, Eva Hughes Maldonado, Somaiya Rowland, Sofia Benitez and Cameron Bates. / Photos by Riley Robinson and illustration by Michelle Lee

January 18, 2018

Last year, there was a running joke in Northeastern’s theatre department centered on then-freshman theatre major and pansexual woman Somaiya Rowland. In her first year at a liberal college in Boston, she felt confident enough to be open about her sexuality. That choice seemed to backfire quickly. A taunt picked up by her classmates implied she wasn’t actually pansexual — she was just faking it, doing it for attention.

“As a freshman, I shouldn’t have had to deal with this in what I thought was a safe space,” Rowland said.

But the source of the taunting wasn’t a homophobic, straight man. The so-called joke was started by one of her gay classmates.

There is a hidden divide within the LGBTQA+ community. People who identify as something other than gay and lesbian have different experiences than the rest of the LGBTQA+ community. These people, who identify as pansexual, asexual and bisexual, suffer specific types of discrimination unlike their gay and lesbian counterparts.

Now a second-year, Rowland said she no longer participates in online groups like the private Facebook group for Northeastern’s LGBTQA+ students. She sees the same people who taunted her about her identity online and she can’t help but be turned off.

“It’s frustrating,” Rowland said. “To [see them] preach acceptance when they have attacked me.”

These divides have real effects on individuals, said Julie Woulfe, an attending psychologist in the outpatient department at Montefiore Medical Center in New York City. Woulfe has done research on how discrimination and misconceptions about bisexuality affect the health of bisexual people.

“It is just now that people are starting to ask about pansexual and asexual as something different,” Woulfe said. “I think that’s a huge area for growth, is to understand subgroups.”

After conducting an online survey of bisexual adults, those who said they were attracted to more than one gender, Woulfe found that many of these individuals felt unsupported by both the queer and straight communities.

“The term people used is double discrimination,” Woulfe said. “They feel they can’t get support from the heterosexual community and they aren’t getting support from the LGBTQA+ community. Experiencing all this discrimination and you don’t have the same buffers, the same support within the queer community, which leaves people vulnerable to poor mental health outcomes.”

She called it a “minority stressor,” or the specific pushback that people face as a result of their sexuality. Rowland’s classmates invalidating her identity and discriminating against her sexual orientation is an example of a minority stressor in her life.

“Bisexual-specific minority stress was associated with poor physical health of adults with bisexual orientation above and beyond sexual minority stress,” read the study, which Woulfe provided to The News in an email. “Addressing this distinct type of prejudice is necessary to improve the health and well-being of individuals with bisexual orientation.”

The lack of community reflected in Woulfe’s findings applies in all situations. However, LGBTQA+ spaces on college campuses can be incredibly important to young people as a support network while they figure out how they identify and come out to friends and family.

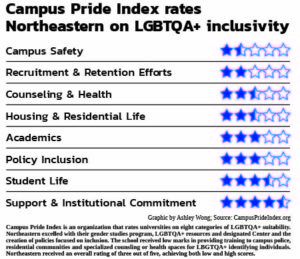

There is a large variance in how friendly a university may be to LGBTQA+ students. Campus Pride Index is a website that ranks — on a scale from one to five — a school’s overall support for LGBTQA+ students, then breaks down further rankings within the university for various aspects of student life. The index also reports if a university has various procedures and support structures in place. The Northeastern University profile was completed by the director of its LGBTQA+ resource center, Lee West, and the Office of Institutional Diversity and Inclusion.

Northeastern has an overall ranking of three stars out of five. In further breakdown, Northeastern rarely scores above a three. The only two exceptions are when the school received a 3.5 for student life and a 4.5 for support and institutional commitment. On the other side, Northeastern received only a two out of five for recruitment and retention efforts, as well as a 1.5 for campus safety.

Northeastern has an overall ranking of three stars out of five. In further breakdown, Northeastern rarely scores above a three. The only two exceptions are when the school received a 3.5 for student life and a 4.5 for support and institutional commitment. On the other side, Northeastern received only a two out of five for recruitment and retention efforts, as well as a 1.5 for campus safety.

Even when their community doesn’t seem ready to accept them, LGBTQA+ students do their best to carry on. Rowland says she tries to find community in her friends with similar experiences, even as she watches them adjust their identity to fit the climate.

“A lot of my pansexual friends say they are bi,” Rowland said. “I use [pansexual] anyways because I am willing to explain. They got too frustrated. It’s a term more comfortable for me.”

A Long History of Erasure

Explaining more complex sexualities can be hard, especially when LGBTQA+ history is often not taught until college, said Bonnie Morris, a lecturer for the Department of Gender and Women’s Studies at the University of California, Berkeley.

“A peculiar problem is that anything that is sexual is banned from schools. They don’t want to bring attention to what they see as a private sex life,” Morris said. “You don’t get the knowledge of how gay people were living or contributing to any country at any time.”

Morris also pointed out that waiting until college to teach LGBTQA+ history makes it far more exclusive. Many people don’t go to college and never get access to information about the LGBTQA+ community, she said. In addition, only the most radical information is given attention in the media.

“Saving gay history until college is a gross disservice. Then it’s a private club,” Morris said. “Or what is now on TV is whatever makes a controversial soundbite.”

Another struggle for those who identify outside gay and lesbian is that, historically, they are often absorbed into the gay movements.

“Doing a history of women who were bisexual is difficult because the assumption was if you’re with a man you’re not really part of the lesbian community per se, you have privilege,” Morris said. “If you’re with a woman you’re participating in lesbian culture.”

However, many organizations with more specific focuses are working to spread the history of forgotten identities. One such organization is BiNet USA, which advocates for bisexual people.

Faith Cheltenham lives near San Francisco and is the vice president of the national organization. She said although today it may seem like bisexuality is new, it has been around for far longer than people think.

“We have bi people throughout history,” she said. “They just disappear off the books. It’s a big part of our history to show that bi people go back that long.”

Cheltenham said despite the fact that bisexual people are often erased, terms like bisexual and pansexual were created back in the 1800s, and there was a large bisexual movement in the 1960s. But today, it seems like bisexuals are supposed to exist in the gaps between straight and gay communities.

“Gay people take care of this part and straight people take care of the rest and bi people fall in the gaping hole in the middle,” Cheltenham said.

Erasure of history affects more than just bisexual people; it also affects asexuals, said Anthony Bogaert, a professor of health sciences and psychology at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ontario. Asexual people do not experience sexual attraction, only romantic. Bogaert also said that some misconceptions about asexuality are due to a lack of visibility.

“It’s clearly the case that people have misconceptions about asexuality,” he said. “Partly because it’s under the radar, socially speaking.”

Real People, Real Effects

Across Northeastern, LGBTQA+ students feel the effects of being kept out of their community.

Eva Hughes Maldonado, a bisexual fourth-year journalism major, said she had some uncomfortable experiences when coming out to her significant others. One time, she came out to her then-boyfriend, who said he thought it was “hot.” She felt like he was fetishizing her sexuality.

“The bi erasure sucks and is real,” Maldonado said. “It’s unfortunate that bi people feel they can’t be a part of the community. It’s a weird gray area.”

Maldonado points out that bisexual people do have different experiences than gay and lesbian people. She said bisexual people don’t always have to come out the same way gay and lesbian people do: They could just date the opposite gender and let people make assumptions.

“For the bi coming out process, it’s different,” she said. “It’s nothing I’m ashamed of, but I don’t bring it up. You can choose to hide under that mask.”

Sometimes the stereotypes of bisexual and pansexual people have negative effects when people do come out, said Sara Atlas, a fifth-year psychology major and pansexual woman. Like Maldonado, Atlas said she has had boyfriends who think her sexuality is hot.

“You know the stereotype, you just want it all,” she said. “People don’t say it to your face, it’s more covert. Just like fetishizing the fact that I like girls.”

Atlas said often times it seemed like people would take any possible relationship less seriously after she told them she was pansexual. She also said she felt like there was often a competition for her to be “gay enough” in order to be allowed in the community.

When she was dating a man, Atlas felt like she didn’t really have the option to go to LGBTQA+ events, because people would assume that she was straight and not want her in that space because of it.

“I never wanted to go to Pride, it just felt unwelcome,” Atlas said. “I felt like I’m not gay enough for this.”

The feeling of not being gay enough is a common theme among students. They feel that they must be more aggressive in their pursuit of the same sex or else their entire identity will be questioned.

In other situations, people say it seems like there just isn’t a space for them, even in more explicitly bisexual online spaces. Sofia Benitez, a fourth-year bisexual electrical engineering major, said she sees a lot of straight people in LGBTQA+ spaces.

“You see ‘I’m just bi-curious’ or ‘we are looking for a threesome,’” Benitez said. “It’s like [they] are taking up space that isn’t [theirs].”

Sometimes when talking to LGBTQA+ people in these spaces, Benitez said she is shut out just for being bisexual. She told the story of a lesbian woman she was talking to online who stopped responding to her messages after Benitez told the woman she was bisexual. And when she goes out, Benitez said, it seems like the assumption is always that she is straight.

“Queer places should be better known,” she said. “It’s often a one-night thing. There still needs to be more work done in and out of the community. Remove the idea of the token queer friend.”

Cameron Bates, a fourth-year computer engineering major, is a gay, transgender man. He said when he attempts to meet people romantically, there are multiple barriers to overcome.

“I want to go out and meet people but it’s hard because I don’t know if someone is straight or queer,” he said. “How do I know they won’t freak out about me being transgender?”

Although Bates said this can be hard to bring up, he would rather do it early.

“I want to know up front if they have any misconceptions,” Bates said. “I want to know if they’re going to treat me like [expletive], treat me like a girl.”

Benitez also pointed out that even when there are LGBTQA+ spaces, they often become tourist spots for straight people to come and gawk. So when LGBTQA+ people do go out, such as to a gay bar, there is no real guarantee that the people in that space are not straight.

This pushback doesn’t go unnoticed by those who are not directly affected by it. Amanda Barbour, a third-year bioengineering major, said she identifies as queer or lesbian, but her girlfriend is bisexual, and Barbour has seen the pushback that she has experienced.

“One thing my current girlfriend has said, she’s met a lot of lesbians who don’t trust her. They say ‘you’re just experimenting,’” Barbour said. “I’m one of the few lesbian people she’s met who didn’t do that.”

Barbour said as she looks further she sees the same debate mirrored with other sexualities. With asexual people, she said she has seen a lot of gatekeeping and people suggesting that asexual people are not “queer enough” to be in the LGBTQA+ community. And when people are more open about their sexuality it can result in more immediate negativity.

“I think it can be a mixed bag,” she said. “If you’re pretty open about your identity it’s easier to exclude you right off the bat, but you don’t waste your time.”

Finding the Connection

It is clear that going forward, the LGBTQA+ community has a lot of work to do. With little research and knowledge on stigma and sexuality, it is unclear what will be the best way to fix the problem.

However, Cheltenham, from BiNet USA, said it is crucial to remember that progress has been made.

“It’s important to know that it’s changed a lot, it’s gotten a lot better,” Cheltenham said. “[We are] celebrating bi characters on TV. At the same time, we don’t have that representation within the LGBT community.”

Bogaert, the psychology professor at Brock, said the study of asexuality is a growing research field.

“I think it is more studied than it once was,” Bogaert said. “It is probably still understudied. It is certainly the case that all areas of research are influenced by interest. Asexuality is, in a strange way, more sexy than it once was.”

Tanekwah Hinds is the women’s health plan coordinator at Fenway Health in Boston, and has run multiple workshops for queer women’s empowerment. She said the most important thing for the LGBTQA+ community is to keep an open mind and listen to people.

“We know gender and sex attraction is fluid,” Hinds said. “There needs to be an acceptance of gender identity and sexual orientation.”

Back at Northeastern, Rowland said she doesn’t have a perfect solution, but something has to be done. Otherwise, the LGBTQA+ community will lose what it is really about.

“I think the biggest thing is respecting boundaries, but not shutting down all conversation,” she said. “It’s a hard balance. There is a culture in queerness and we are losing that.”

Correction: The print version of this story failed to include the story of Cameron Bates, which was not The News’ intention. We apologize for this error.