By Morgan Lloyd, campus editor

Local activist and community organizer Aaron Tanaka offered students a lesson in alternatives to capitalism in a Jan. 18 speech in the John D. O’Bryant African-American Institute.

The event, hosted by Students Against Institutional Discrimination, or SAID, drew a crowd of dozens to hear Tanaka speak about different economic systems and activist strategies.

“Capitalism is only a system that’s been around for a few hundred years,” Tanaka said. “For us, it feels like there is no alternative to capitalism, that’s the only way you can be. But let’s remember actually it’s only a tiny fraction of human history in which we’ve been organized and driven by the profit motive.”

Tanaka is the founder of the Center for Economic Democracy, a Boston-based organization described on their website as “building a vision for a new economy” through community initiatives.

Tanaka started the event by asking the crowd to stand based on their answers to two questions. First, do you feel capitalism can be equitable? Second, how comfortable are you in your ability to articulate alternatives to capitalism?

Overwhelmingly, the students in attendance felt capitalism was inherently inequitable. Far fewer, however, felt as comfortable explaining any alternatives, a fact Tanaka hoped to help change.

“This is a huge topic. It’s not really something you can get that deep into in an hour, an hour and 15 minutes,” Tanaka said. “For me, the hope is to give you some basic frameworks and give you some examples so you can take this and go out on your own and get involved in activist organizations that are doing this work.”

Tanaka discussed the concept of the means of production, or land, labor and capital. Capitalism, he said, allocates these resources based on a profit-driven motive. Any alternative to capitalism has to find another way to utilize these means.

Tanaka then spoke on the intersection of capitalism, racism and sexism. Prasanna Rajasekaran, SAID’s co-director of political education, thinks is a deeply important issue.

“I would say it’s not possible to separate them,” said Rajasekaran, a fifth-year economics major. “Obviously, all of those things, as Aaron explained, are all connected. There’s no attacking the one and not attacking the other.”

As Tanaka said, the Industrial Revolution played a large role in reinforcing gendered labor roles to allow men to work in factories while women stayed at home. Similarly, Tanaka mentioned how the idea of “whiteness” in the United States was developed to divide slaves and poor whites, both of whom were oppressed by the rich plantation owners of the time.

“The transition of capitalism was a deeply violent transition,” Tanaka said.

The discussion turned to the rules of capitalism, for which students brainstormed possible alternative solutions. After leading the discussion, Tanaka offered some theories himself, seeking to break down different types of potential economic models.

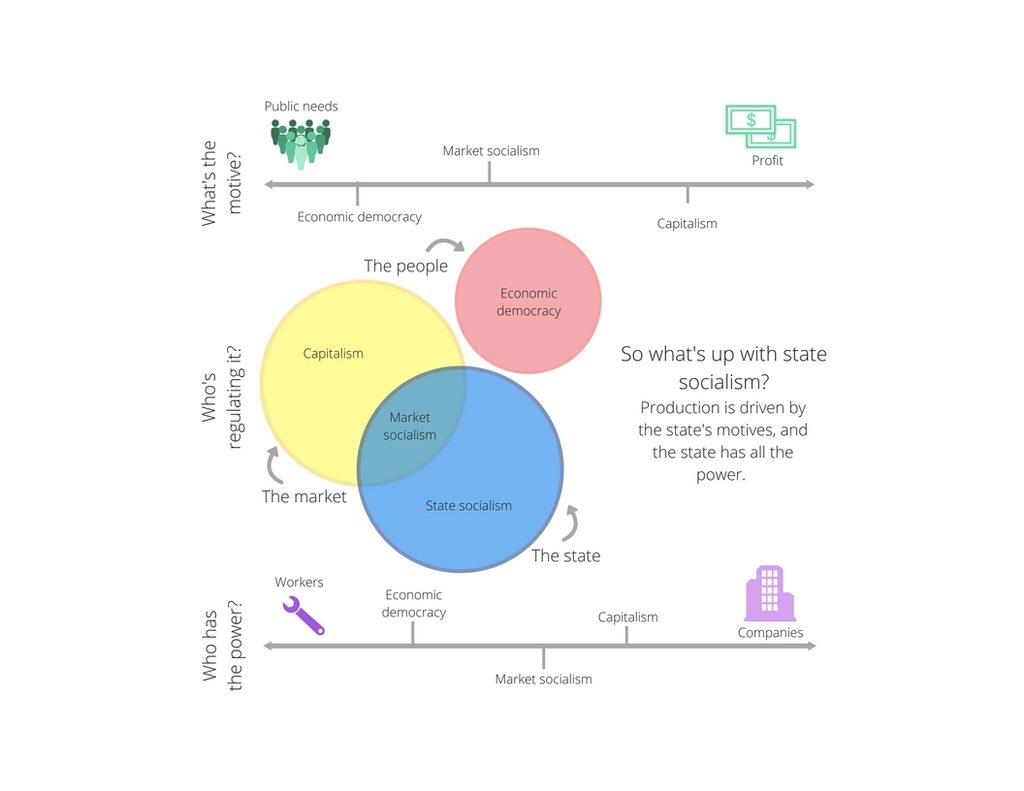

Tanaka mentioned three systems in particular. The first was market socialism, where businesses are owned by their workers. The second was state socialism, where businesses and the entire economy are run by the state. The third was economic democracy, where decisions about the economy are made by voters.

“I love this conversation, but people don’t have it very often,” Tanaka said. “If you asked a random person on the street, ‘What’s your favorite type of socialism?’, they’d be like, ‘What the hell are you talking about?’”

Tanaka pointed to an organization he helped create, the Boston Ujima Project, as an example of an alternative economic theory in practice. This organization invests money based on decisions made by community investors. Each person has an equal vote on where funds are invested, regardless of how much money they have contributed. Part of the project’s model involves pressuring hospitals and universities to not only divest from fossil fuels, but also reinvest in their community.

“You have so much capital, and a lot of it has been accumulated through extraction,” Tanaka said. “Now you’re investing in fossil fuels and prisons. Instead, you should divest this money, which is what a lot of people are working on, and now we’re adding this layer that you should reinvest that capital into community-controlled funds.”

The event concluded on a question on the role of people with various forms of privilege within activist movements.

“Especially if you’re going to school at Northeastern, or a private university, you’re going to have an amount of wealth that is considered a privilege. You have power, no matter what,” Rajasekaran said. “A big part of organizing is being very self-aware — understanding your blind spots, the things you can’t see because of your privilege and power, and listening to people when they call you out on that.”

Rachel Domond, the vice president of SAID and a third-year sociology major, hoped the event would leave students better informed about political activism.

“The whole point of our club is political education,” Domond said. “We’re trying to get people to a base understanding of how structures work and how they serve to marginalize different groups of people based on the intersections of all their identities, so that they can go out and do what they want with that and hopefully make structural change.”