Apple allows Northeastern-created app into store after ban

February 1, 2018

Although Apple originally refused to allow an app created by a Northeastern-led research team on the App Store, the company relented after public outcry.

The app, Wehe, was created by a research team led by Northeastern assistant professor David Choffnes and detects net neutrality violations.

Choffnes has been interested in the topic of net neutrality for years and began researching how to detect violations when he came to Northeastern. His team developed an app that would allow users to test if their internet service providers, or ISPs, were slowing down, or throttling, the traffic on their phones.

“Going forward, rules are clearly changing over time,” Choffnes said. “The enforcement priorities of a given regulator change with the administration, so I do want to assemble a large body of data that can be used to inform policy debates as we continue to revisit this issue.”

The drive to create that body of data led Choffnes and his team to create an app so that the general public could easily test for violations.

Wehe monitors whether ISPs are slowing down traffic to certain apps by sending video traffic, then disguising it and comparing the results, Choffnes said. This allows Wehe to show users what speed they are getting for an app and what the speed would be if their ISP was not slowing it down.

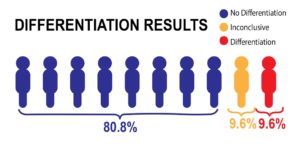

“When you see a case like this, AT&T on LTE with NBCSports, we have 130 of these tests and 85 percent of these have differentiation,” Choffnes said. “They’re throttling NBC video, that is clear.”

However, simply throttling video is not illegal. Most ISPs have it written in the fine print of consumers’ cell contracts that they slow down video traffic. However, Wehe allows Choffnes and his team to prove that ISPs aren’t slowing down all video, which would be a violation of net neutrality.

“I’m not trying to claim that AT&T is doing this on purpose or any other network is singling out one application versus the other, but it’s when they make such decisions that there could be unfair disadvantages or advantages for some providers versus others,” Choffnes said.

Before Wehe could run enough tests to show that these disadvantages were real, it would have to get onto the Apple App Store.

Choffnes submitted the app for review Dec. 14, the day the FCC voted to change the net neutrality rules. To Choffnes’ surprise, Apple replied in several weeks to reject the app.

“They said it was misleading because they thought it was a speed test app, which is not what we do,” he said. “We test whether network traffic gets different throughout depending on whether it looks like a certain application or not. But we are not actually testing what is the maximum speed of your ISP.

The other thing they said was that it had no value for users, which just stung a little.”

Choffnes appealed the decision and was rejected again, even after submitting papers and research that showed that Wehe was not a speed test app. At that point, he took to Twitter, and people were outraged. He said it became the number-one read story on Reddit the next day. There was already an Android version of the app, and it was quickly overwhelmed by the sudden increase in users.

Apple did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Fangfan Li, a third-year computer science Ph.D. student, worked on the project on the server side. He was the first to see the flood of users.

“I got here around 9:30 and I was checking the mailbox and I saw a complaint email. It said ‘Hey, your server is down,’” Li said. “Because by that time we have barely any users, I was like, ‘ah what?’ We only have 200 users and the server is down. Let me double check, maybe I did something really stupid.”

He went to check the servers, but thought the server must be under attack as a result of the increase in connections.

“I sit in the conference room and Dave [Choffnes] came and I told him, ‘I believe our server is under attack, what should I do?’ He was like, ‘Oh, let me take a look,’ and he realized really fast, ‘Oh no, those are legit users,’” Li said.

Li and Choffnes spent the rest of the day working to add more servers to the app.

“When we were fixing the server, there were just calls coming in for Dave and one call was from Apple. ‘Your app is approved!’ In the middle of trying to fix the server, ‘Oh wow, we are going to have more users. We need to bring up more servers for that,’” he said.

Kirill Voloshin, a fifth-year computer science and business administration combined major, worked on the project as a co-op. He helped with the Android app and built the iOS app from the ground up.

When Wehe was rejected, Voloshin was confused and upset.

“It was very frustrating because I spent a lot of time working on it and I was paid for that time so it was money wasted,” he said. “I didn’t know what to do, because we appealed the rejection multiple times and nothing we were doing was helping. It was very depressing.”

Voloshin said that it was unfortunate they had to go through so much effort to get Apple to approve Wehe, but in the end it worked out because now they have significantly more users.

He also said he was surprised by the reaction, but hopes that people will continue to follow the net neutrality debate.

“I’m hoping it makes people pay more attention, because net neutrality is kind of a technical area. Sometimes it’s hard to explain why it’s important,” Voloshin said. “But an app like this one, it specifically shows you ‘this is the speed you could be getting, and this is the speed you actually get’ when you are watching a YouTube video. So the user can see the impact.”