Increased concern over climate change prompts Boston to take action

November 28, 2018

As sea levels rise and storm surges start to occur more often, coastal cities in the Northeast rush to prepare themselves. Boston is no exception.

Mayor Martin J. Walsh unveiled a plan Oct. 17 titled “Resilient Boston Harbor.” With a series of sea walls, buffers, open space and elevated landscapes, this plan aims to protect Boston from rising sea levels.

In addition, the Climate Ready Boston initiative, led by Program Manager Mia Mansfield, launched in 2015. The initiative currently has four projects underway: Coastal resilience plans in East and South Boston, flood reduction and community improvement in Charlestown and a collaboration with the Parks Department to redesign Moakley Park in South Boston to make it more resilient.

“The goal [of the initiative] is to better understand and prepare for climate change from now to the end of the century,” said Mansfield, who has a master’s degree in city planning from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “We work with the university community and translate their predictions into short-term and long-term vulnerability plans.”

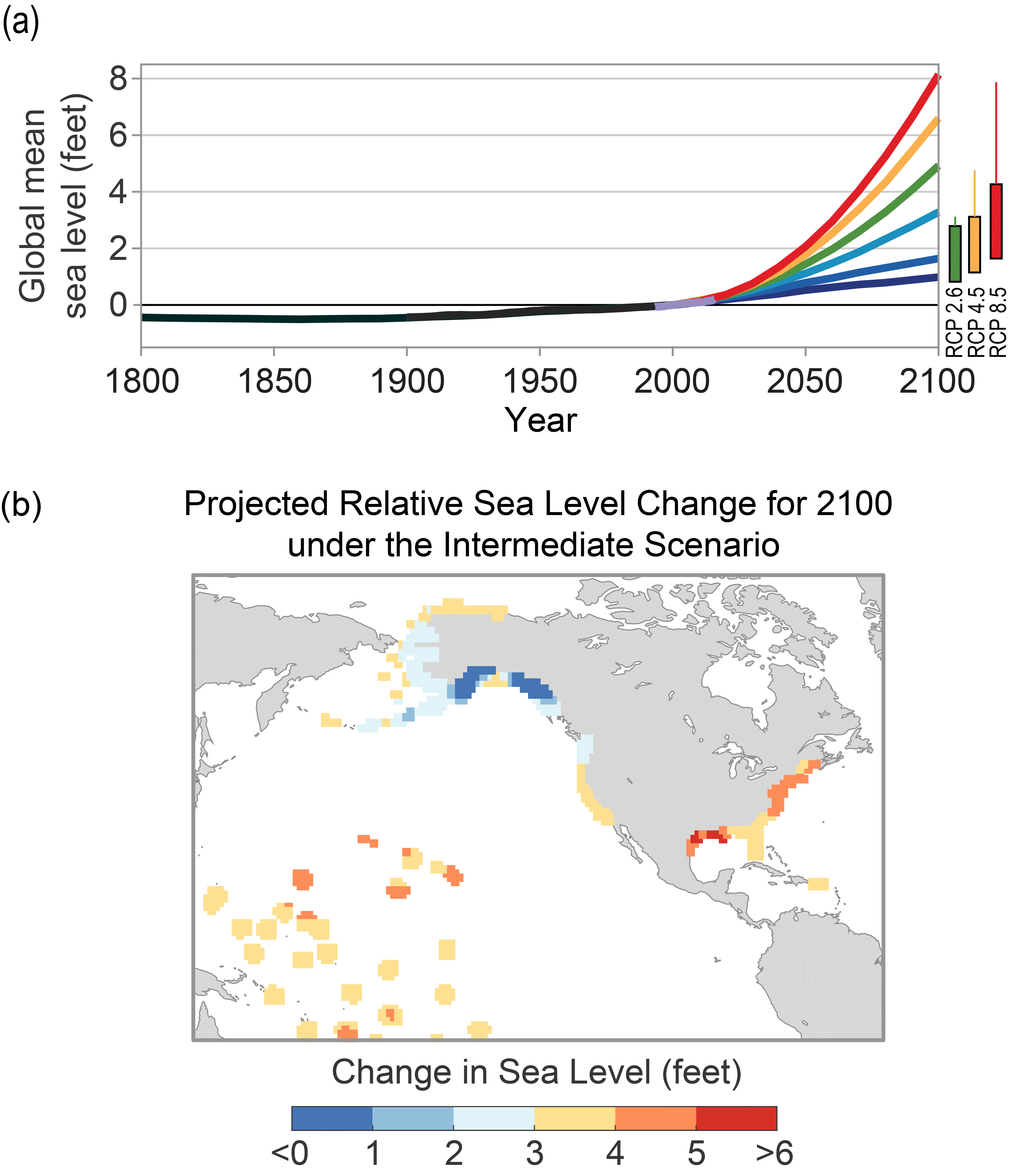

On Tuesday, the United Nations released a report that states that if all countries continue with their current emission targets, the global temperature will rise an average of 3.2 degrees Celsius by 2100. This would mean intense consequences for sea level rise, human health and the economy.

In addition, a study published in 2017 by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, or PNAS, found that rising sea levels caused by climate change will increase the overall flood impact associated with major storms. Based in Washington, D.C., PNAS is one of the world’s leading scientific journals.

The study combined model storm surges with sea-level rise projections to assess coastal flooding in New York City from the preindustrial era to the year 2300. The results show that the water level of floods so severe that they only occur once every 500 years will increase by up to 40 feet above mean tidal level from 2005 to 2300.

Although the study was focused on New York City, the findings have implications for many coastal cities in the northeast. Boston is especially prone to coastal flooding because much of its coastline is built on areas that were artificially created by filling in wetlands in the 1800s.

“There’s a definite need for us to take actions to make our coastal communities more resilient,” said Andra Garner, one of the authors of the PNAS study. “Although I don’t think we’re quite prepared enough in many cases, I do know that coastal adaptation planning is well under way in many areas.”

Although Boston’s risk of flooding will increase over time, new infrastructure can be used to manage the risk. Amsterdam, the capital of the Netherlands, can serve as an example. The city lies on the North Sea Canal, about 7 feet below sea level and uses man-made structures such as surge barriers, artificial dunes, and the elevation of houses and roads to turn flood-prone areas into green areas that tend to be more resistant to flooding, said Thomas Wahl, an associate professor of Coastal Risks and Engineering at the University of Central Florida.

“Even though there are big storm surges and the city lies below sea level, they are not at risk because of man-made structures,” Wahl said. “Therefore, they are exposed but not vulnerable.”

In 2007, Amsterdam developed “room for rivers,” a concept where planners allow rivers to expand when large amounts of water enter them, instead of fighting it with the traditional dike system. Amsterdam is no longer vulnerable, with the chance of their flood protection system failing being one in 10,000, Wahl said.

Planning and preparing for the impacts of climate change in coastal areas is essential, Wahl said. In 2017, he worked on a study, that found in the year 2050, “only a tiny tropical depression will be needed to create the same level of water as caused by [Hurricane] Florence.”

Garner agrees that coastal flooding is a major concern, especially for the East Coast.

“We know that tropical cyclones are particularly hazardous for the U.S. Atlantic coasts and sea-level rise will continue to worsen the flooding events we see associated with storms in the future,” Garner said. “When we combine this with the fact that coastal populations and infrastructure have been and continue to grow, we see that risk for these regions is indeed increasing.”

As major storms start to dominate the news more often, Boston citizens are starting to look for ways to be more involved in preparing their city for climate change. One of these ways is the Greenovate Boston Leaders outreach program. This program aims to train local leaders to educate their community on climate change readiness. So far, the program has trained 143 leaders and reached 1,364 residents.

Climate Ready Boston also emphasizes community engagement, making use of focus groups and community meetings in the formulation of their resiliency plans. The initiative’s website also has progress trackers and reports readily available to keep residents informed.

Although the initiative is focused on planning more than emergency management, a representative from the public health or emergency management department is present at most meetings, Mansfield said.

The task that the initiative is taking on is a big one. The program works with the private sector, state organizations, federal organizations, community groups and philanthropic groups in order to better achieve its goal of protecting the city and its residents.

“There is nothing we can do about the possibility of extreme events; we can’t tell a hurricane to go away. We can’t do much about exposure; we can tell people to leave but they won’t go,” Wahl said. “But we can control vulnerability.”