Students seek alternatives to UHCS

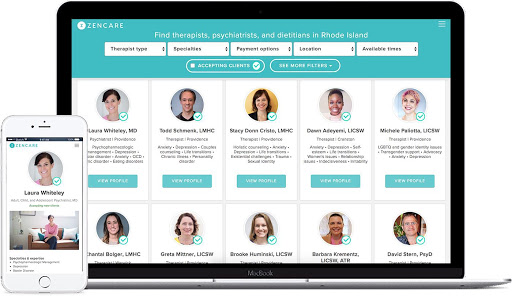

Zencare is a website that allows those seeking mental health professionals to find one that works for their specific needs.

January 30, 2019

Katrina Kalamar didn’t bother stopping by Northeastern’s University Health and Counseling Services, or UHCS, as a first-year student to find a therapist in Boston, even though the center exists to help connect students to the care they need.

“I heard it was very difficult to see a therapist there and I had been seeing one weekly since before college,” said the now fifth-year media and screen studies major. “I couldn’t take a gamble on getting lost in [the center’s] shuffle.”

Kalamar ended up finding care on her own, outside of the university system. Her decision is not an isolated case; if anything, it’s the norm. The reputation of Northeastern’s health center precedes itself to the point that many students bypass it entirely, taking their search for mental health care into their own hands through platforms like Zencare, a digital service that matches people to therapists in New York, Greater Boston and Rhode Island.

Student activists have urged the university to provide more funding and staffing for UHCS so students feel supported as they seek care, but the movement to improve the center has yet to pick up any meaningful gains.

“Students are not really happy with UHCS; [it] isn’t a functional health care service for students,” said Olivia Clark, co-founder of the now-defunct Students Working for an Accessible Northeastern, an unofficial student organization dedicated to making success attainable for students with mental and physical disabilities. “There needs to be a really drastic change to the way health care, and particularly mental health, is dealt with at Northeastern.”

UHCS did not reply to comment for this story, but according to their website, the university currently employs 10 behavioral health clinicians for all 17,506 undergraduates at Northeastern, or one for every 1,751 students. This ratio falls short of the standards laid out by the International Association of Counseling Services, which encourages universities to have one counselor per 1,000 to 1,500 students.

Northeastern’s counseling staff also pales in comparison to that of nearby research universities like Massachusetts Institute of Technology or Harvard University, both of which employed approximately one counselor per 170 students as of March 2018. The school with the closest ratio is Berklee College of Music, which is still lower than NU at roughly one counselor per 1047 students.

This understaffing makes it hard for UHCS to offer long-term mental health care to Northeastern’s student population. UHCS instead refers students to therapists or health care providers outside of the university system based on the students’ symptoms. UHCS’ website says its clinicians generally meet with students once to evaluate their needs and provide these referrals, and only have follow-up appointments for further assessment, leaving students to coordinate any actual meetings with a long-term care provider on their own.

In addition, UHCS only allows students to book mental health appointments over the phone, instead of online. This creates a problem for those with social anxiety who struggle to make phone calls.

Laura Camila Rivera, a fifth-year marketing and interactive media combined major, said this policy is deeply flawed. Rivera said she came to UHCS looking for care during her first year due to feelings of depression that kept her from leaving her room and interfered with her school work. Her counselor told her the center would send her options for treatment after their meeting.

“They never did,” Rivera said. “And so I gave up, because I was depressed and I wasn’t able to work that hard.”

Rivera went without treatment that year, but when the depression recurred the following year, she returned to UHCS looking for recommendations once more. She said the counselor on that occasion said they would send her options after the meeting. They once again didn’t. Returning a few weeks later finally got Rivera the recommendations she needed, but she didn’t feel like any of them were equipped to deal with both her depression and her past experience with bulimia nervosa.

Rivera continued two more years without care until she found a therapist in the fall of 2017 through the website Zencare. Rivera doesn’t blame the counselors she spoke to for her bad experience with UHCS, but rather the policy preventing them from meeting with her more than once about her care.

“I don’t think there should be only one meeting allowed,” Rivera said. “You become real to them at that point, and [they] can follow up and make sure you’re getting what you need.”

Zencare has become a common avenue Northeastern students explore in trying to find a therapist without going through the university’s system. The web platform enables users to search according to their issues, age, preferred method of treatment and even insurance provider.

Yuri Tomikawa, 28, established Zencare in 2015 to help students at Brown University in Providence find therapists due to increased demand for mental health services and difficulties finding care through their university health center. The service expanded into the Boston area in September 2016.

“For all the heat that college counseling services receive, I think they’re trying their best,” Tomikawa said. “They’ve suddenly been inundated with requests, and it’s the first time the number of students seeking help are rising.”

To meet these rising needs, Tomikawa recommends university health centers follow a three-fold approach: Ensure they hold slots for students who strongly want to come in same-day, clarify that their ultimate goal is to connect students to long-term care outside the center and provide subsidized on-campus care to students who have no means of paying for therapy otherwise.

In Northeastern’s case, though, it’s unclear how the university will offer better care without additional funding. Kalamar, Clark and Rivera said, considering the university’s multimillion-dollar endowment, the administration certainly has the money to prioritize funding the health center for its students.

“Northeastern is an institute that has so much money,” Clark said. “And I feel like if they invested that money in the students, I think that would be more beneficial than their current investments.”