NU’s Sexual and Gender-Based Harassment policy fills gaps left by federal Title IX overhaul

“At the end of the day, what I want to make sure that all students know is that the protections haven’t changed,” said OUEC Deputy Coordinator and Investigator Brigid Hart-Molloy.

September 30, 2020

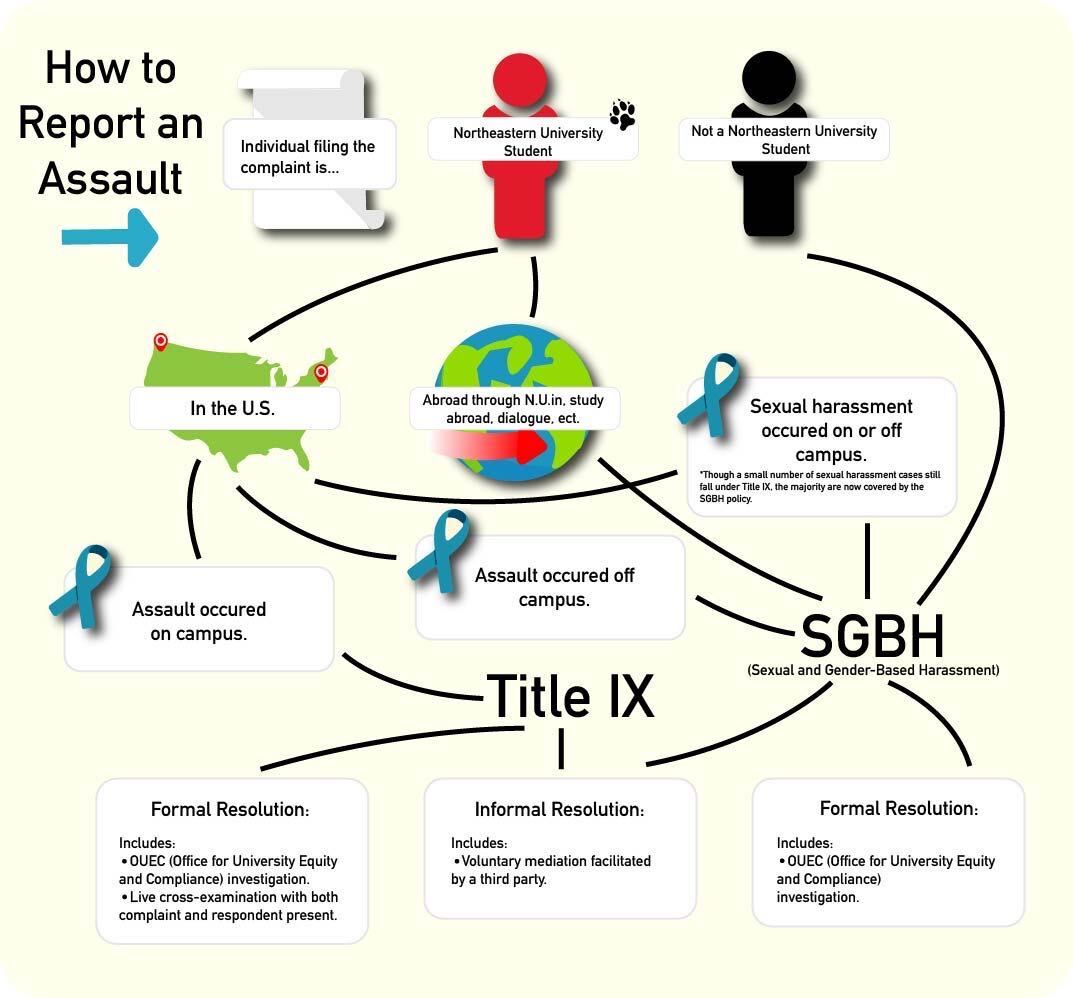

Northeastern University has updated its Title IX policy in accordance with changes mandated by U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos and the U.S. Department of Education. In response, Northeastern’s Office for University Equity and Compliance, or OUEC, has created a new policy on Sexual and Gender-Based Harassment, or SGBH, to protect students against instances of sexual assault and harassment that are no longer covered under the updated Title IX policy.

The Title IX policy changes went into effect nationwide Aug. 14 after a federal judge struck down a New York State and New York City Board of Education lawsuit against the Department of Education. The updated guidelines apply to all schools that receive federal funding, including private colleges and universities.

The revised policy has made several key changes in the ways schools approach investigating and resolving allegations of sexual misconduct. It has also drawn harsh criticism from women’s rights organizations and sexual violence prevention groups for narrowing the scope of misconduct that can be investigated by schools, and increasing protections for perpetrators of sexual violence.

“Schools now dismiss any sexual misconduct that happens outside of campus-controlled buildings or educational activities,” said second-year politics, philosophy and economics major Kate Petka, who heads the Title IX Transparency Initiative at Northeastern’s Interdisciplinary Women’s Council. “So what that means is if I am sexually assaulted in my off-campus apartment by another member of the Northeastern community, Northeastern is not responsible under Title IX to investigate that.”

This mandate is expected to curtail the number of Title IX cases schools are responsible for investigating, especially considering the majority of reported sexual assaults at many universities occur off-campus, according to the Associated Press. It also eliminates Title IX protections for students studying abroad and reduces protections against sexual harassment, allowing students to file a complaint only if the harassment is sufficiently severe.

To ensure that students still have avenues to report instances of sexual assault and harassment they experience outside of Title IX’s jurisdiction, Northeastern’s OUEC created the SGBH policy over the summer with input from Northeastern’s Sexual Assault Response Coalition, or SARC.

“We knew that there was only a month and a couple of weeks for anything to be done,” said SARC President Tali Glickman, a fifth-year psychology major. “We wanted there to be policy in place when students got to campus at the beginning of September.”

The new SGBH policy closely mirrors the old Title IX regulations, encompassing instances of sexual assault that occur off-campus, during a study-abroad program such as N.U.in, or against someone who is not a Northeastern student. It also includes the lower-level sexual harassment that is no longer covered under Title IX’s jurisdiction, such as catcalling.

“There are universities across the country that did not create a second policy,” said Assistant Vice President for University Equity and Compliance and Title IX Coordinator Mark Jannoni at a presentation on Title IX policy changes hosted by SARC. “There are universities across the country that said, ‘Title IX, it is what it is.’ But we didn’t think that was the right thing to do, so we created this policy that addresses behavior that happens either on or off campus, either in the context of a university education program or not, or in the United States or not.”

The new Title IX guidelines have also eliminated guidelines from former President Barack Obama establishing a 60-day timeline for resolving allegations of sexual assault. However, the OUEC has voluntarily committed to a 90-day timeline, extending the deadline to account for the two 10-day review windows mandated by the Department of Education.

“At the end of the day, what I want to make sure that all students know is that the protections haven’t changed,” said OUEC Deputy Coordinator and Investigator Brigid Hart-Molloy, who also spoke at the presentation. “The policy under which protections fall may have changed, but we are still responding to all allegations or concerns of sexual harassment, sexual assault, domestic or dating violence, sexual exploitation, and stalking.”

However, one aspect of the new Title IX guidelines has carried over to the SGBH policy: instances of sexual assault that are reported to the OUEC will no longer immediately trigger an investigation.

“For us to be able to do anything now, we need a formal complaint,” Hart-Molloy said. “Prior to the changes, there were often scenarios where folks would come to us and say, ‘This thing happened, but I don’t want to do anything about it.’ And we would have to move forward with some sort of response or action, because that’s what the law required of us. That’s no longer true for the most part.”

Under the new Title IX guidelines, students who report a sexual assault (now referred to as “complainants”) must submit a signed, written complaint to the OUEC alleging a Title IX-prohibited offense and ask the university to take action against the perpetrator (now referred to as “respondents”). Mandated reporters, such as resident assistants, will still be required to disclose instances of sexual assault, domestic and intimate partner violence, sexual harassment and stalking to the OUEC, but there is now a greater level of flexibility for survivors when it comes to opening an investigation.

“Once we are put on notice, we reach out to the complainant to offer the opportunity to speak to us, so we can go over all of their choices, both informal and formal,” Jannoni said. “That way they can make the best decision for them.”

Northeastern’s Title IX and SGBH policies both contain formal and informal avenues for resolutions. However, students whose reports fall under Title IX will now be required to submit to a live cross-examination in front of their assailant as part of the formal resolution process, a move that has angered a lot of sexual violence survivors and advocates.

“There’s now policy in place to ensure that perpetrators are the priority,” Glickman said. “Cross-examination is a tool that is used to break survivors, rather than an investigation or a conversation that is used to understand what happened and reach an agreement for proposed sanctions … It’s now about proving character defamation and buying into a lot of stigma that surrounds sexual violence cases.”

During the cross-examination process, both the complainant and the respondent must choose an advisor to cross-examine the other party. A Title IX hearing board, composed of two faculty members and one student, will be present for the cross-examination. There will also be a designated decision maker to moderate the questions from each party’s advisor and dismiss any that are deemed irrelevant.

“I can’t say this enough: This is a requirement of federal law,” Jannoni said. “This is not a Northeastern, OUEC, Mark Jannoni [policy]. This is, ‘if you do not do this, you can lose your federal financial aid.’ If we want to say for the record, do we agree with this? We absolutely do not. Which is why, when I got here five years ago, we removed the hearing process to move to the investigative model.”

Survivors who do not wish to undergo cross-examination can instead choose to pursue mediation through the informal resolution process. Students who pursue a formal resolution under the SGBH policy will not be cross-examined. However, SARC is hoping to work with the OUEC to improve the resolution process for survivors seeking justice.

“We’re hoping that a restorative justice process comes into fruition,” Glickman said. “From the research that we’ve been doing at SARC, it hopefully can be a space where perpetrators admit harm, and a space where perpetrators understand their guilt and and listen to what the survivor needs rather than getting defensive within an investigation process. We’re hoping that formal resolution can turn into a space that feels way more healing for survivors.”

The university sent out an email to students on Sept. 21 outlining the updates to Northeastern’s Title IX policy. However, Petka worries that the information will be drowned out by the influx of COVID-19 news and information from the university.

“We just want people to know that this is going into place, because if I wasn’t aware of what Northeastern was doing, because I hadn’t talked to Mr. Jannoni, I would have no idea,” she said. “I would think that the Title IX policy is the Title IX policy, and if I got sexually assaulted in my off-campus apartment tomorrow, I would have no idea that I could still go about complaining and reporting in some other way.”

Students who wish to file a Title IX complaint can do so using this form. Students who want to file a complaint under the new SGBH policy should use this form.