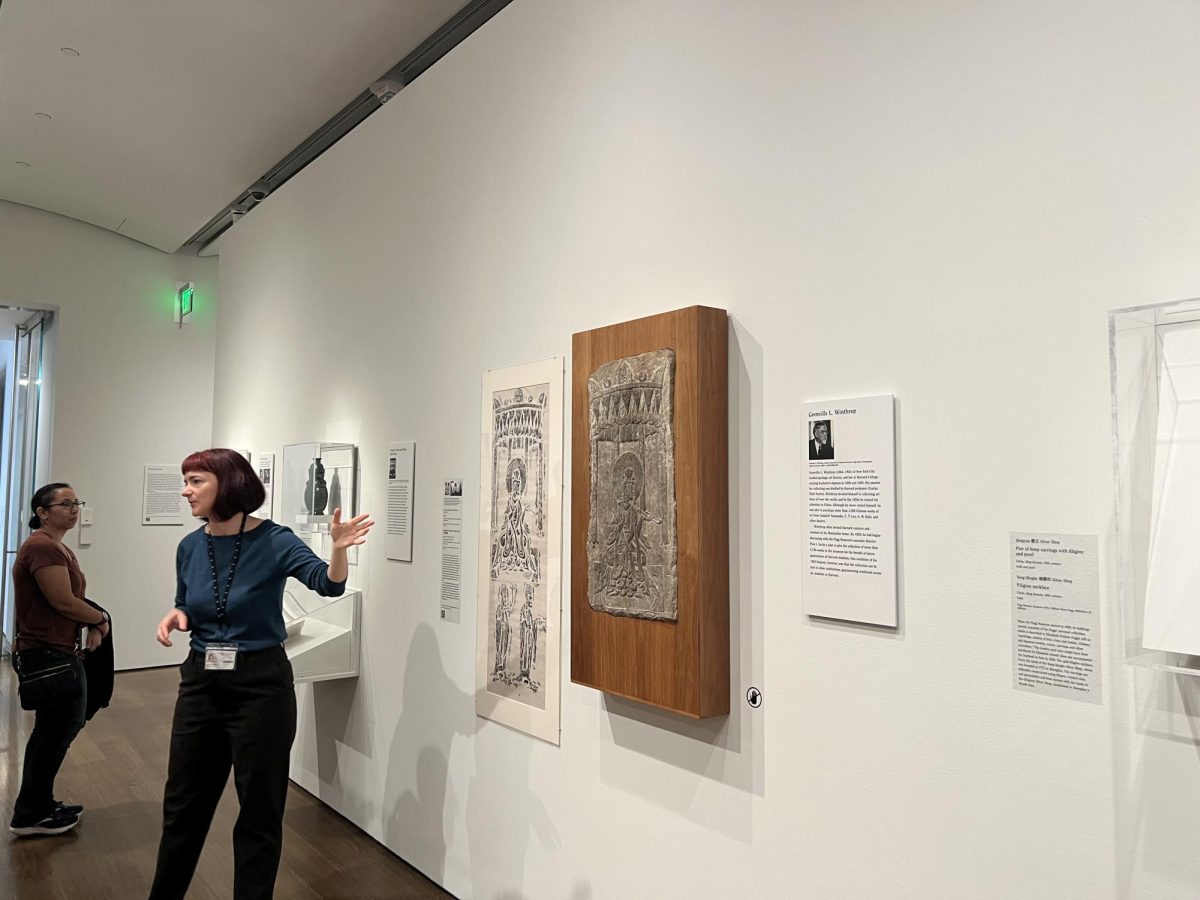

A small group of art lovers, history buffs, former academics and habitual “if-it-interests-me” museumgoers gathered on the third floor of the Harvard Arts Museum Oct. 18. Attendees joined curator Sarah Laursen as she hosted an intimate gallery talk on her fall exhibit, titled “Objects of Addiction: Opium, Empire and the Chinese Art Trade.”

Currently residing in the museum’s Special Exhibitions gallery, the “Objects of Addiction” exhibit consists of a thoughtfully assembled collection of paraphernalia, artifacts and artwork from, or associated with, opium-era China. According to booklets offered at the gallery’s entrance, “the exhibition explores the entwined histories of the opium trade and the Chinese art market in the late 18th and early 20th century.”

The exhibition details the participation of Massachusetts-based merchants in the Western opium trade. Displayed works demonstrate how domestic taste in Chinese art was shaped by international conflict and later, by anti-Chinese sentiment and immigration policies within the United States.

Laursen’s inspiration for putting together the exhibit stemmed from feeling like there was a blind spot in the education she received growing up in Boston, she said.

“I grew up in the Boston area and attended public school, and I did not learn about the history of the opium trade,” Laursen said. “That’s why we have the booklets that are also available in the exhibition so that people can come away with that information and share it with others.”

In contrast, attendee Lola Chen, originally from China and now a student at Harvard Medical School, said she studied many of the details of this history in her early education in China. Chen said that she appreciated how the exhibit brought her face-to-face with works representative of the events of this era while also acknowledging the perspective from which they are being valued.

“It’s really impressive to see all these items, which are evidence of what I learned, in real life and from the Western side,” Chen said.

The exhibit presents this layered history in a manner that is both compelling and deeply self-aware. The displayed works do not shy away from the realities of Western involvement in the opium trade, nor does the exhibit fail to address the legacy of this participation today. During Laursen’s talk, she spoke critically about the Boston families that profited from this trade.

“These objects only became available in the West because of the Opium Wars, which resulted from Western imperialism in China. I think looking back as far as we can to acknowledge the places where we ourselves have benefited from this tragic history, and not hide that, is important,” Laursen said in an interview.

For Tim Roberts, an exhibit attendee, Laursen’s transparency towards this exploitation really resonated. He said the exhibit illustrates a very simple, yet persistent, human concept.

“It’s all fascinating, how people have made their money in the past and how people continue to make their money out of other people’s misery,” Roberts said.

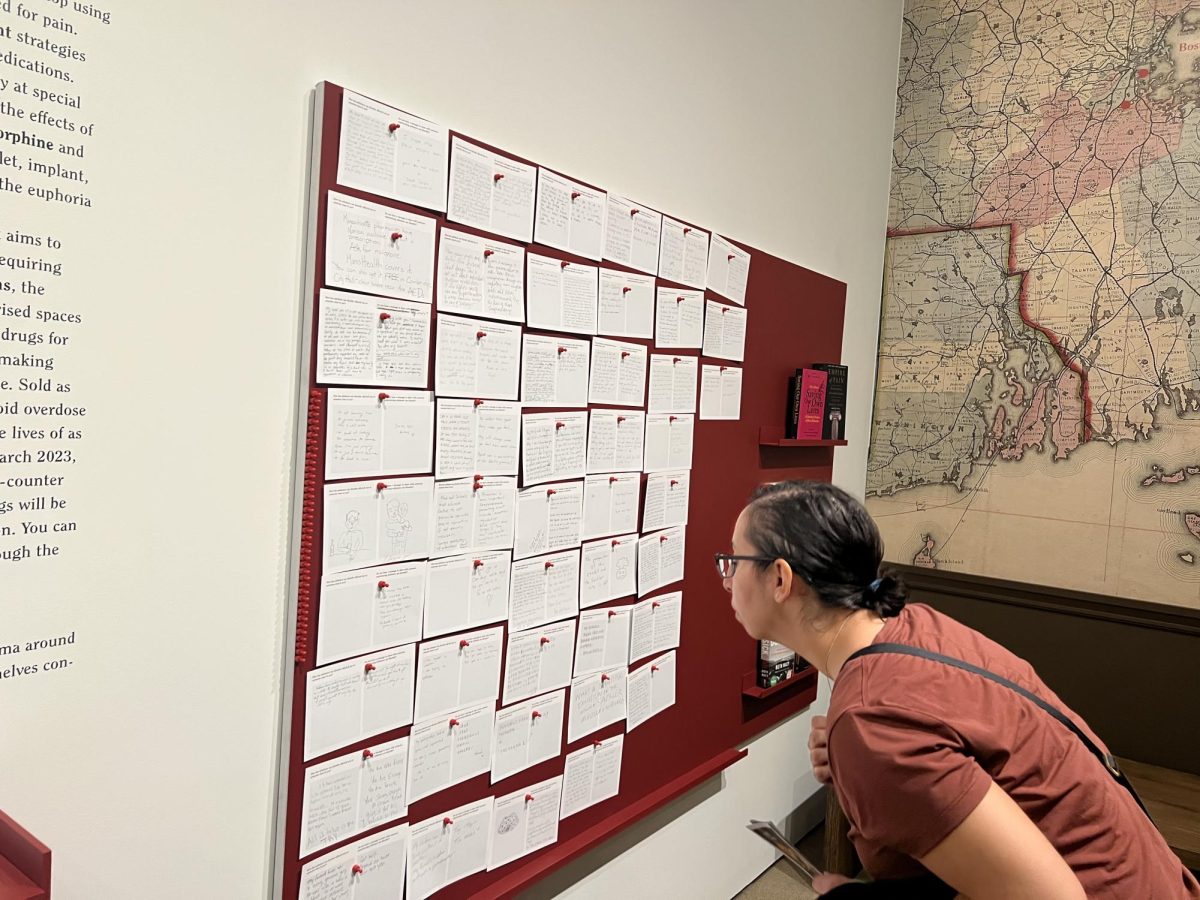

The significance of the exhibit is cemented through the consolidation of opium’s past with the implications of its present. One section of Laursen’s exhibition considers today’s opioid crisis by combining educational tools with a powerful interactive display. On the far wall of the gallery, public health information that answers questions such as “What are opioids?”, “What is addiction?” and “What can we do?” sit side-by-side a corkboard that invites museumgoers to share their own experiences with opioids or addiction on pinned-up comment cards.

“I think we now have English, Spanish, Portuguese and Chinese contributions to that wall. It shows how broad of a population opioids affect,” Laursen said.

Many contributors expressed heavy messages and passionate appeals.

“I’m still learning how to grieve someone who is still alive. I’m tired of looking for someone to blame. Now I’m just praying to a god I don’t believe in to find a cure,” said one anonymous author of a comment card.

Another contributor shared a plea to the government: “I have a message to our government to ask how these dangerous drugs are infesting our neighborhoods and killing indiscriminately. Stop the flow of these dangerous drugs,” they wrote.

Using this exhibition as a platform to address opioid addiction and remove some of the stigma around the individuals struggling with this disease was one of Laursen’s objectives when creating “Objects of Addiction,” she said.

“I think being very clear that nobody walks into this wanting to be addicted to opium or opioids really helps people generate more empathy and be more open to supporting that community,” Laursen said.

The “Objects of Addiction: Opium, Empire, the Chinese Art Trade” exhibition is on display at the Harvard Art Museums until Jan. 14, 2024.

![A demonstrator hoists a sign above their head that reads, "We [heart] our international students." Among the posters were some listing international scientists, while other protesters held American flags.](https://huntnewsnu.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/image12-1200x800.jpg)