Mass. and Cass, the colloquial name for the area at the intersection of Massachusetts Avenue and Melnea Cass Boulevard, is notorious for its long history of homeless encampments and open-air drug use. On November 1, the intersection was completely cleared out after an ordinance filed by Mayor Michelle Wu passed Oct. 25.

The ordinance, filed Aug. 28, came after increased violence in the area which spiked this past summer. It was created in an effort to “boost public safety and eliminate the violence and criminal activity that can undermine service delivery,” the ordinance reads.

Boston Police officers cleaned the intersection of encampments and relocated inhabitants to shelters and treatment centers. Enforcement allegedly occurred only after individuals were offered adequate housing, shelter and transportation and given the opportunity to move their personal belongings.

But city council members were initially hesitant to pass the ordinance due to feelings that it wouldn’t solve the overarching crisis of scarce housing and few drug treatment options for Mass. and Cass inhabitants, which is why it stalled in conversations and hearings up until the 60-day deadline, when a proposed ordinance is automatically enacted.

“The sweeps and clearing of encampments have failed in every single city that has attempted this,” Councilor Ricardo Arroyo said at the Oct. 25 vote, where he was one of three councilors to vote ‘no’ to passing the ordinance.

Amendments were made to the ordinance by Arroyo throughout the deliberation process, leading the council to vote ‘yes’ in a 9-3 majority, allowing the clearing of encampments to take effect the following week.

Amendments to the ordinance included removing the $25 fine for violators and ensuring a Boston Public Health Commission involvement in cases where shelter space is limited, but Mass. and Cass residents are displaced from encampments with nowhere to go.

Concerns about rising violence and drug use at Mass. and Cass prompted the council to push for a state of emergency declaration in early September, working with the Boston Public Health Commission to look for solutions. Wu’s ordinance was not accepted as the solution to Mass. and Cass by many well-versed in the effects of encampment sweeping patterns, as expressed in opinions voiced at a governmental operations hearing Sept. 28, that was headed by Arroyo.

Councilor Erin Murphy opened the September hearing by saying the tragedy at Mass. and Cass concerning drug use and violence was “unprecedented in Boston’s history in its severity and duration.” She said she hoped the hearing would pave the way to handling the crisis in a “very safe and humane manner.”

The immediate action of clearing the encampments was seen as a positive benefit of the ordinance to Council President Ed Flynn.

“[The tents] must be removed from public spaces immediately,” Flynn said. “The status quo is not an option and we must provide positive leadership to address this emergency.”

Despite councilors expressing adamance that action must be taken immediately, other councilors and members of the community panel felt there was a better and more permanent way to promote a public health solution.

Dr. Avik Chatterjee, medical director of the Southampton Street Shelter Clinic, has been overseeing patients from the Mass. and Cass area since 2015.

“The biggest threat to public safety I would argue are overdose deaths,” he said.

Chatterjee said that overdose deaths become less frequent, and overall safety is increased when people reside in groups. He said the encampment area at Mass. and Cass helps people feel supported by a community and allows emergency medical services to easily locate patients when faced with emergency situations. On occasions when homeless concentrations have dispersed, he said emergency medics have been unable to quickly reach patients due to the spread of drug usage into random alleys.

In advocating for a prevention center rather than a sweep, Chatterjee said, “there’s no evidence that [dispersing the tents] makes the needles go away and people stop using drugs. Sweeping it away is not going to make it go away.”

Cassie Hurd, executive director of Material Aid and Advocacy, has worked with unhoused people in the Boston area for the past 17 years. “This is not a public health proposal,” she said. “This is doubling down on inhumane and ineffective police actions and will result in increased harm and potentially preventable death.”

Hurd’s main concern with the ordinance is how it gives law enforcement the ability to evict people with little to zero notice. Hurd offered alternative solutions including permanent low-threshold housing, more overdose prevention centers and increased education.

However, the most impassioned argument at the hearing against the ordinance pertained to how it can’t guarantee available housing for everyone who needs it. Instead, it may further displace a population of people seeking shelter.

Dr. Lara Jirmanus, a physician at the Cambridge Health Alliance, said the public health approach to the crisis must put permanent, stable housing first, along with evidence-based involuntary drug treatment. This refers to Section 35, a Massachusetts law that allows a qualified person to request for someone to be treated involuntarily for an alcohol or substance use disorder.

Many are also concerned that there simply won’t be room at the local shelters for everyone relocated from the Mass. and Cass area.

“I’ll come out of the clinic at 8:30 and the cafeteria will be full of people sitting there, whose bed for the night is the chair they’re sitting in,” Chatterjee said about the Southampton Street Shelter.

There are currently six low-threshold sites that provide temporary shelter and substance use resources. Murphy said the city is working urgently to replace services to accommodate the large influx of residents these sites will see in the days after the ordinance passes.

“It’s difficult to see how this will work and where all these people will go,” Chatterjee said. “[The shelter] is already 100 people over capacity and demand gets higher as it gets colder.”

Chatterjee is concerned for the future of the shelter because he said if residents plan to work a job, they would have to stop working by 1 p.m. to ensure a bed for the night. After residents claim a bed, they are not allowed to leave the shelter before nightfall at the risk of losing it.

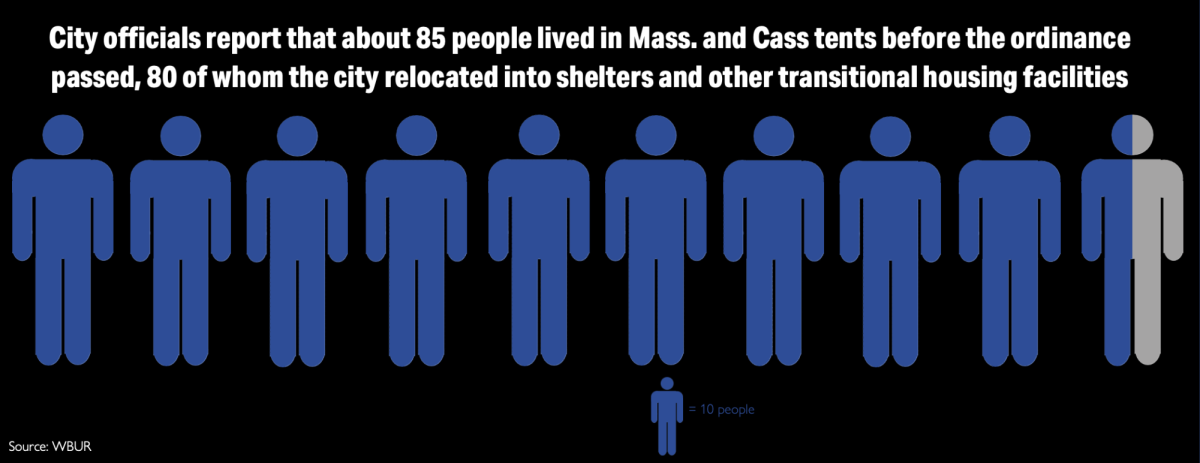

Since the ordinance passed, about 80 Mass. and Cass inhabitants have been moved to temporary housing in emergency shelters, homes for recovering addicts and mental health facilities, according to WBUR data.

So far, the ordinance appears to have taken effect smoothly, according to Wu’s comments at a press conference this week. She said that the peaceful dismantling of Mass. and Cass marked the beginning of a new, collaborative effort to connect people struggling with mental health and substance use problems with social services, according to reporting in the Boston Globe.

Yet, some community members are still unsure about the effectiveness of the ordinance in the longevity of protecting Boston’s homeless and those who struggle with drug use.

“This is a complex issue,” said Mark Martinez, a Roxbury resident. “It is the complexity of the issue that makes the vagueness of the ordinance inadequate to address the problem. Too many things are left open to question.”

He said the ordinance could either be the first step in improving quality of life and helping the homeless population move off the streets permanently, or create adverse results of displacement, spreading drug use and violence to other parts of the city.

“We won’t know if it works until it is too late,” Martinez said.

![A demonstrator hoists a sign above their head that reads, "We [heart] our international students." Among the posters were some listing international scientists, while other protesters held American flags.](https://huntnewsnu.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/image12-1200x800.jpg)