The Food and Drug Administration, or FDA, authorized a 4-milligram naloxone hydrochloride nasal spray for over-the-counter sales, or OTC, in March. This was in an effort to reduce overdose deaths primarily caused by illicit drugs. However, as of December, those in the medical field shared the need for increased accessibility to the life-saving nasal spray for it to have a widespread impact in Boston.

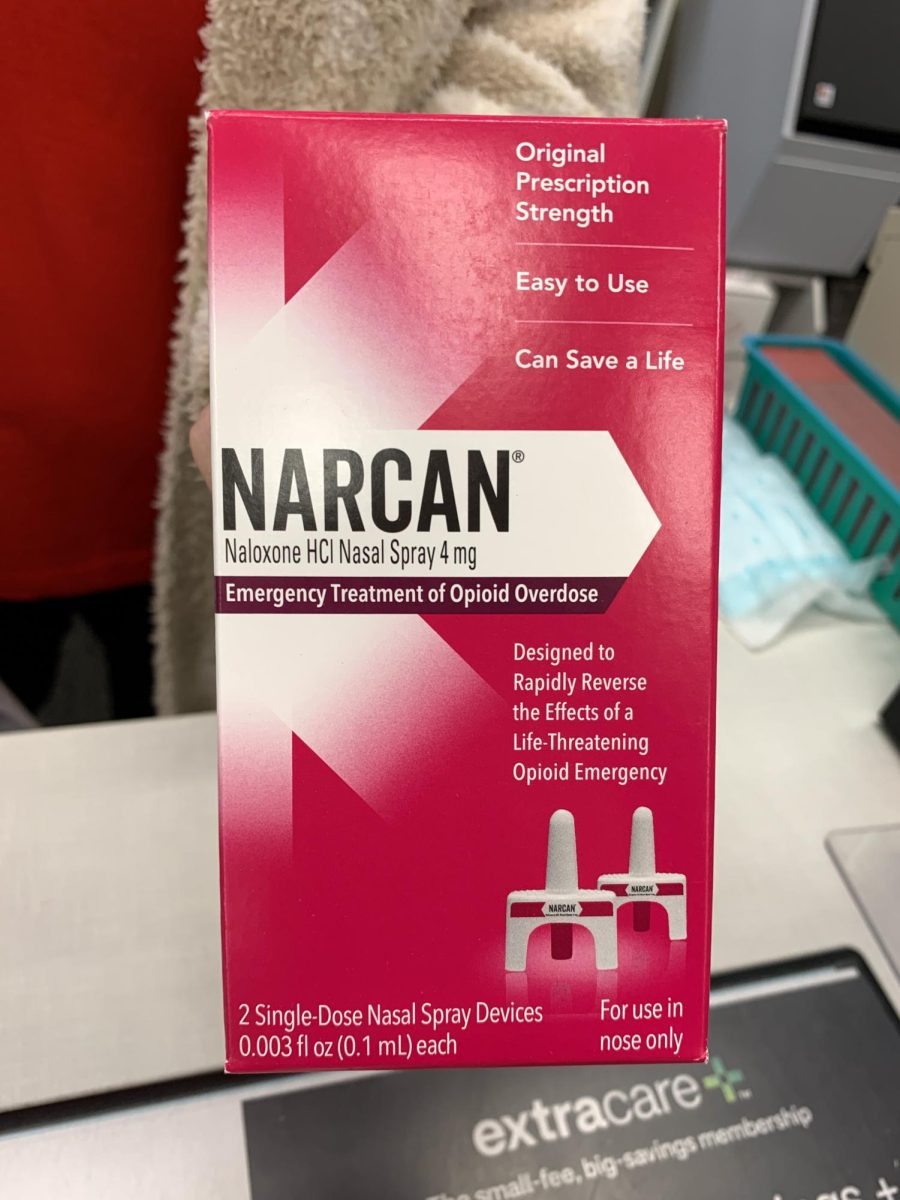

Naloxone rapidly reverses the effects of opioid overdose and was previously only accessible by prescription. Still, even with removing the prescription requirement, experts say naloxone isn’t getting into the hands of the people who need it most.

“We haven’t seen or heard a massive uptick in people accessing [naloxone],” said Gracie Rolfe, a senior project manager at Health Resources in Action, or HRiA, a non-profit organization focused on public health consulting in the Boston area.

Overdose deaths have continued to steadily increase each year nationwide. In 2022, drug overdose claimed more than 109,000 lives in the U.S. Boston hit a record high of 2,359 opioid-related deaths in 2022, a 2.5% increase from the year before. Fentanyl accounts for the most drug-related deaths in the U.S.; the substance was detected in 93% of individuals who experienced fatal overdoses in Massachusetts last year.

“Overdoses increased exponentially in the last few years. That’s in large part due to fentanyl entering the drug supply, which is far, far deadlier than heroin,” said Katelyn McCreedy, a population health sciences doctoral student and research lead at the Action Lab at the Center for Health Policy and Law at Northeastern.

McCreedy said the COVID-19 pandemic likely led to a combination of factors making overdoses more deadly. Increased social isolation resulted in people administering drugs alone without someone there to help if an overdose occurred. Heightened stress and restricted access to harm reduction resources and treatment were also contributing factors.

Since the effort to make naloxone OTC began, not much has changed for unhoused people in the state, said McCreedy. Various roadblocks stand in the way, including the cost.

“The approval of naloxone over-the-counter isn’t really something that’s going to have a significant impact in terms of getting Narcan to the people who are most in need. About one in four people experiencing homelessness die of a drug overdose in Massachusetts. The barrier to getting it was never just that you needed a prescription, but primarily the cost,” McCreedy said.

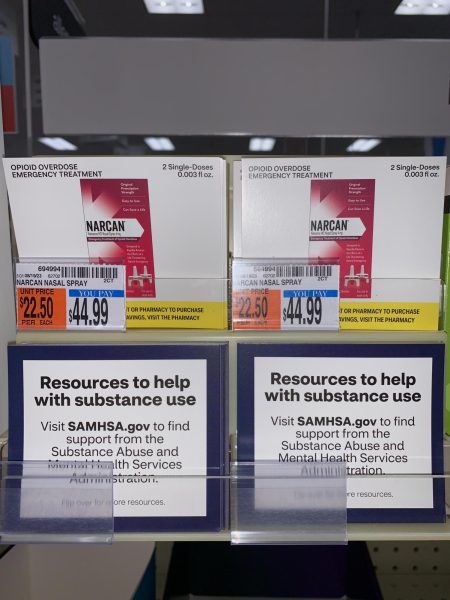

The shelf price of Narcan, the leading naloxone brand, is $45 for two doses. Narcan can be found nationwide at CVS, Walgreens, Walmart and Rite Aid, but it remains unaffordable to those in need. RiVive, a lower-cost alternative manufactured by a harm-reduction nonprofit pharmaceutical company, Harm Reduction Therapeutics Inc., is $36 for two doses.

“If you happen to be opioid dependent and perhaps unhoused, but you absolutely need to get a certain amount of your daily dose of opioids — if you have $45, it’s going to your opioid addiction to maintain that addiction. You’re not going to have it to run to the CVS,” said Mark Gottlieb, the executive director of the Public Health Advocacy Institute at Northeastern University School of Law.

Naloxone becoming OTC is just a small piece of the larger harm-reduction strategy needed to tackle the complex public health issue of substance use disorder. There remains a lack of employment, mental health support and housing options, according to Brandon Craig, a doctoral student and instructor of criminology and criminal justice at Northeastern University.

“Housing is something that everyone needs at a basic level, and it’s often not something that’s guaranteed. If you don’t have stable housing, it’s very difficult to go through substance use treatment and obtain other healthcare,” Craig said.

Craig said there needs to be a substantial change in support and outreach for those struggling with opioid addiction.

“I do think that in terms of reducing harm for people who continue to use opioids, Narcan definitely will be helpful. But in terms of the long term overall, I think there’s still a lot of systemic change that needs to happen, particularly in access to substance treatment programs,” Craig said.

Gottlieb said he urges for a widespread education program on the administration of naloxone.

“I don’t believe that most of the population has any clue that this is an option for them now. This is a relatively new policy. I think a broad education program is needed so that people know that it’s available and how to use it, because it’s not that hard to use, but you do need some instruction,” Gottlieb said.

The City of Boston offers a training program on the administration of naloxone. Each year, about 10,000 individuals participate in this basic training.

“For us and for most harm reduction groups, the goal is not to completely stop illicit drug use. The goal is to help mitigate the harms associated with drug use,” McCreedy said.

Rolfe said that she sees a need for strategic change to address the opioid crisis.

“In the past, [the approach] was police, incarceration and criminalization. We have so much data now that this doesn’t solve public health issues,” she said.

Drug use is a complex and stigmatized issue that still requires research and empathy for progress to be made, Gottlieb said.

“There is so much work to do in this area that it’s almost overwhelming, but we have the medication. We have the ability to provide medical care to these folks and to provide mental health services,” Gottlieb said. “It’s just whether we have the will as a society to provide them that will ultimately determine the morbidity and mortality associated with substance use disorder and related mental health issues.”

![A demonstrator hoists a sign above their head that reads, "We [heart] our international students." Among the posters were some listing international scientists, while other protesters held American flags.](https://huntnewsnu.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/image12-1200x800.jpg)